"God Help American Science": Engineering Theatre and Spectacle

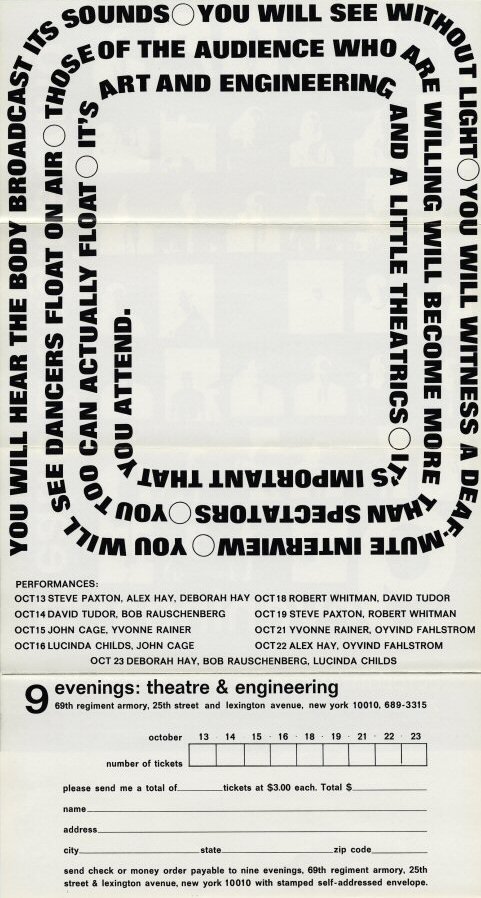

When your event’s promotional poster promises that, for a mere $3 a ticket, “You will hear the body broadcast its sounds * You will see without light * You will see dancers float on air” and concludes with “It’s Important That You Attend,” there’s bound to be some disappointment. The location for 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering only fed into audience and critics' anticipation. Television host Hugh Downs introduced 9 Evenings to the Today Show’s audience as an event of potential historical import. “53 years ago,” he said, “an exhibition took place at the 69th Regiment Armory here in New York that stunned America. It came to be called the Armory Show. And it was a bombshell that introduced modern art to this country.” Before bringing on Billy Klüver, the Bell Labs engineer who was 9 Evenings’s ringmaster, Downs concluded, “Beginning tomorrow, that Armory is going to be the scene of something that might be equally interesting.”Klüver’s appearance on Today was one just component of a weeks-long publicity campaign led by Ruder & Finn, the public relations firm hired to promote 9 Evenings. Press releases were sent to more than two dozen magazines and newspapers including those specializing in art as well as engineering.

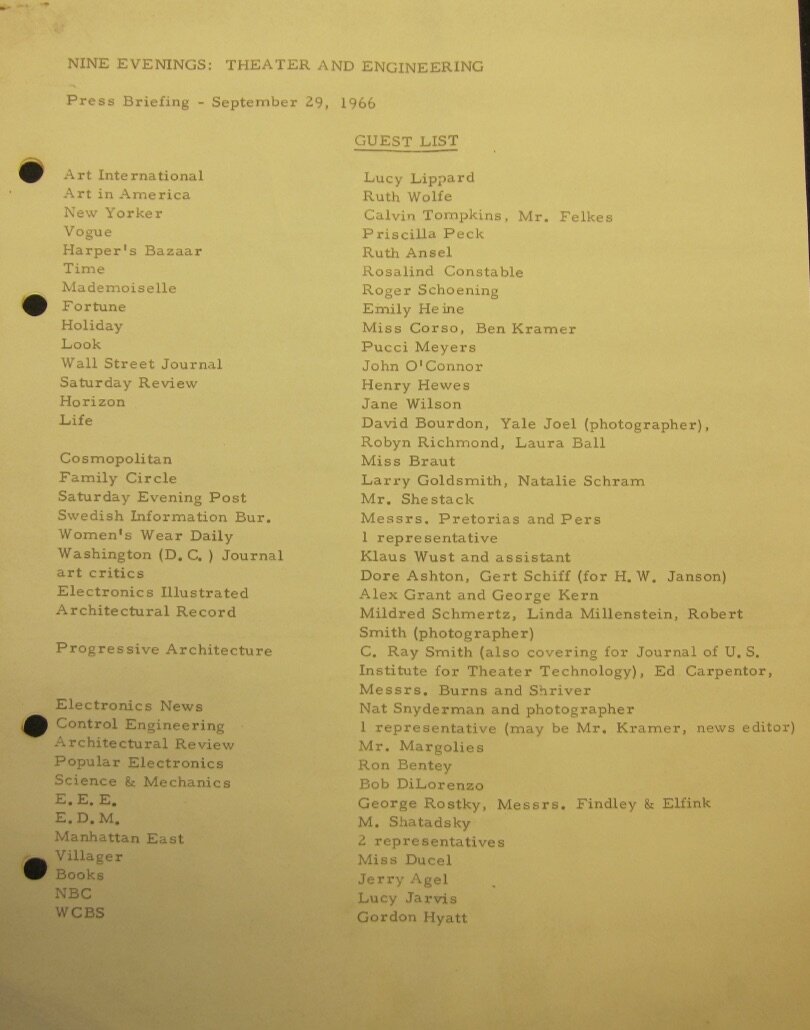

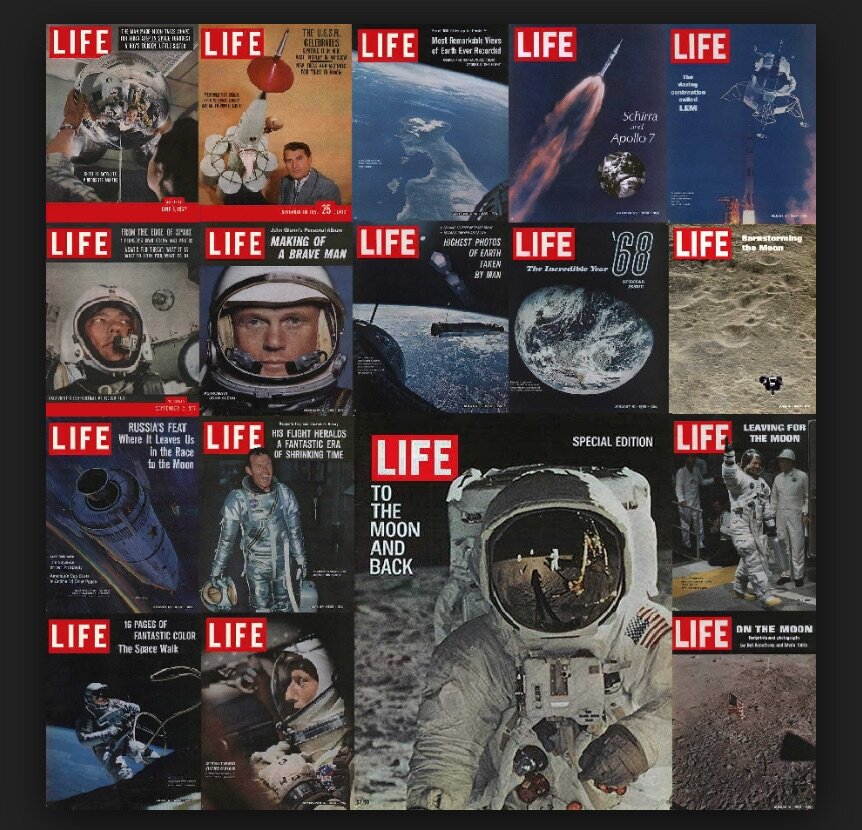

The location for 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering only fed into audience and critics' anticipation. Television host Hugh Downs introduced 9 Evenings to the Today Show’s audience as an event of potential historical import. “53 years ago,” he said, “an exhibition took place at the 69th Regiment Armory here in New York that stunned America. It came to be called the Armory Show. And it was a bombshell that introduced modern art to this country.” Before bringing on Billy Klüver, the Bell Labs engineer who was 9 Evenings’s ringmaster, Downs concluded, “Beginning tomorrow, that Armory is going to be the scene of something that might be equally interesting.”Klüver’s appearance on Today was one just component of a weeks-long publicity campaign led by Ruder & Finn, the public relations firm hired to promote 9 Evenings. Press releases were sent to more than two dozen magazines and newspapers including those specializing in art as well as engineering. In August 1966, for example, Life told its millions of readers about the current vogue for kinetic art. This medium, Life’s writer noted, often required input from technical experts like Billy Klüver, the “Edison-Tesla-Steinmetz-Marconi-Leonardo da Vinci of the American avant-garde.”Robert Rauschenberg, who had won the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale two years earlier, was the most visible of the artists participating in 9 Evenings when it came to publicity. Finn and Ruder, for example, explored the possibility of the artist performing his 9 Evenings’ piece, titled Open Score, on the Ed Sullivan Show. A few weeks before 9 Evenings started, Rauschenberg hosted a late afternoon press briefing at his studio on Lafayette Street in Greenwich Village.

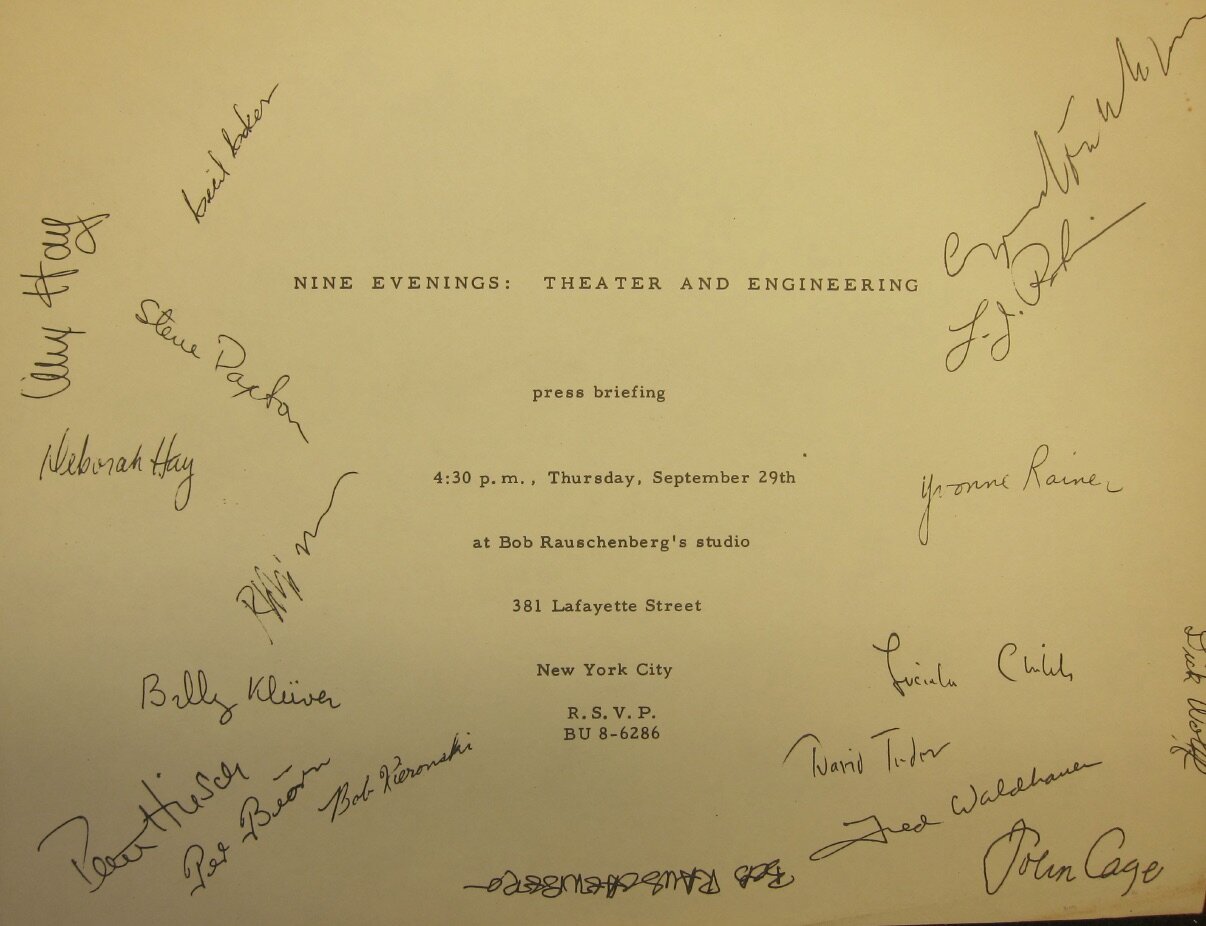

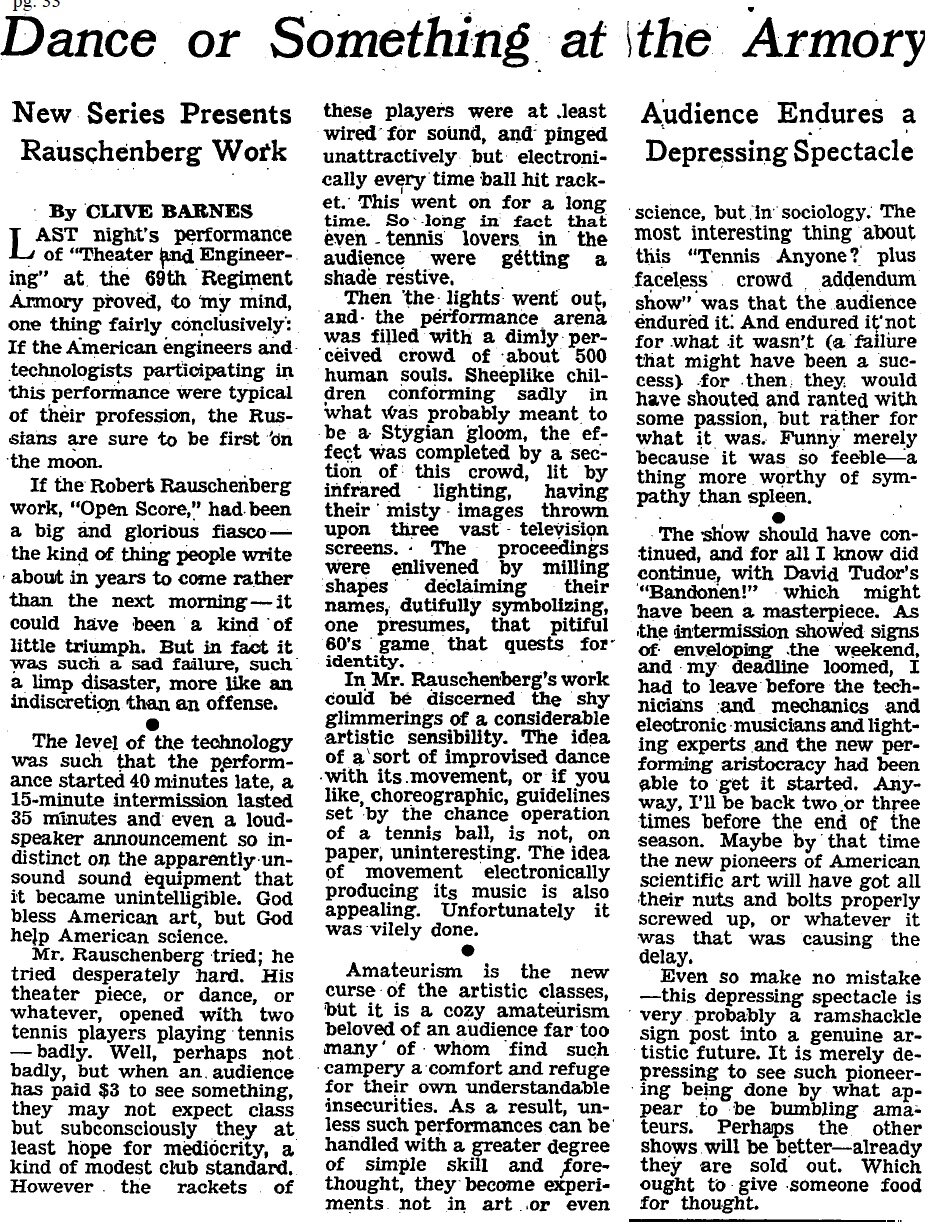

In August 1966, for example, Life told its millions of readers about the current vogue for kinetic art. This medium, Life’s writer noted, often required input from technical experts like Billy Klüver, the “Edison-Tesla-Steinmetz-Marconi-Leonardo da Vinci of the American avant-garde.”Robert Rauschenberg, who had won the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale two years earlier, was the most visible of the artists participating in 9 Evenings when it came to publicity. Finn and Ruder, for example, explored the possibility of the artist performing his 9 Evenings’ piece, titled Open Score, on the Ed Sullivan Show. A few weeks before 9 Evenings started, Rauschenberg hosted a late afternoon press briefing at his studio on Lafayette Street in Greenwich Village. In addition to journalists from local and national publications, the guest list included prominent gallery owner Leo Castelli and Marian Javits, wife of Sen. Jacob Javits, who morally and financially helped support Klüver’s efforts to wed art and technology. In addition to comments from Klüver, artists John Cage, Öyvind Fahlstrom, and Deborah Hay described the pieces they were working on to the guests and journalists circulating through Rauschenberg’s airy studio.The press blitz appeared to pay off as positive articles about 9 Evenings and the larger art and technology endeavor appeared. John Gruen, a cultural critic writing for the short-lived New York World Journal Tribune, predicted 9 Evenings would be a “landmark of sorts” and a “means of expanding the sensibilities of everyone concerned – the artist, the engineer, and the audience.” When the New York Times Magazine profiled Rauschenberg the week before 9 Evenings debuted, he was dubbed a “playwright and engineer.” Rauschenberg claimed that artists were “surrounded by materials and technologies that are too refined to be commonly known.” But, thanks to Klüver and his Bell Labs colleagues, they could now hope to work with these “without letting technology be the theme itself.” 9 Evenings opened on October 13, 1966 with fresh breezes of favorable publicity wafting about the Armory space.Much of this good will, however, evaporated soon after opening night, replaced by a blizzard of negative reviews – some sincere, some snarky – of the much touted event. Imaginably, for the 30 or so engineers who had contributed some 8500 hours of their time pro bono to 9 Evenings, the most cutting comments came from Clive Barnes, an influential British dance and theatre critic at The New York Times. Barnes had attended the first two evenings but walked out, frustrated with “an intermission that showed signs of enveloping the weekend” on the second night. Besides excoriating Rauschenberg’s Open Score (“such a sad failure, such a limp disaster…vilely done”) his October 15 review – written in the midst of the Space Race – opined that “if the American technologists participating in this performance were typical of their profession, the Russians are sure to be the first on the moon.” 9 Evenings was a “depressing spectacle” that audiences endured. “God bless American art,” Barnes wrote, “but God help American science.”

In addition to journalists from local and national publications, the guest list included prominent gallery owner Leo Castelli and Marian Javits, wife of Sen. Jacob Javits, who morally and financially helped support Klüver’s efforts to wed art and technology. In addition to comments from Klüver, artists John Cage, Öyvind Fahlstrom, and Deborah Hay described the pieces they were working on to the guests and journalists circulating through Rauschenberg’s airy studio.The press blitz appeared to pay off as positive articles about 9 Evenings and the larger art and technology endeavor appeared. John Gruen, a cultural critic writing for the short-lived New York World Journal Tribune, predicted 9 Evenings would be a “landmark of sorts” and a “means of expanding the sensibilities of everyone concerned – the artist, the engineer, and the audience.” When the New York Times Magazine profiled Rauschenberg the week before 9 Evenings debuted, he was dubbed a “playwright and engineer.” Rauschenberg claimed that artists were “surrounded by materials and technologies that are too refined to be commonly known.” But, thanks to Klüver and his Bell Labs colleagues, they could now hope to work with these “without letting technology be the theme itself.” 9 Evenings opened on October 13, 1966 with fresh breezes of favorable publicity wafting about the Armory space.Much of this good will, however, evaporated soon after opening night, replaced by a blizzard of negative reviews – some sincere, some snarky – of the much touted event. Imaginably, for the 30 or so engineers who had contributed some 8500 hours of their time pro bono to 9 Evenings, the most cutting comments came from Clive Barnes, an influential British dance and theatre critic at The New York Times. Barnes had attended the first two evenings but walked out, frustrated with “an intermission that showed signs of enveloping the weekend” on the second night. Besides excoriating Rauschenberg’s Open Score (“such a sad failure, such a limp disaster…vilely done”) his October 15 review – written in the midst of the Space Race – opined that “if the American technologists participating in this performance were typical of their profession, the Russians are sure to be the first on the moon.” 9 Evenings was a “depressing spectacle” that audiences endured. “God bless American art,” Barnes wrote, “but God help American science.” Other reviews appeared throughout 9 Evenings’ run at the Armory that took a similar line. John Gruen, who had initially supported the ambitious alliance between artists and engineers, called the opening night “dismal, dismaying…a flop and farce” exacerbated by delays and technical difficulties. For Patrick O’Connor, a dance writer for The Jersey Journal, the whole affair had the air of a big rip-off. Could you believe, he asked readers, that 1,500 people (i.e. suckers) had paid good money to get into 9 Evenings while another 1,500 were turned away? O’Connor knew “the big guns were out” when a “beautiful lady in a maroon and gray reversible raincoat” marched up to poet Allen Ginsberg and said “You probably don’t remember me but I’m Susan Sontag…More chic than that you can’t get.” He advised his culture-seeking Jersey readers to instead visit Manhattan’s Latin Quarter club where “the girls don’t even wear pasties anymore.”Not all reviews were knee-jerk negative or designed to discomfit. Brian O’Doherty’s lengthy post-mortem for the new magazine Art and Artists accurately judged 9 Evenings as being less about its two main ingredients, theatre and engineering. It was instead, he said, a “criss-cross of traditions, disciplines, time-streams, and audiences” which produced a “huge short-circuited tangle.” And, depending on which strand one followed – art, theatre, or technology i.e. the worlds of the artist or art critic versus that of the engineer – “you can end up with entirely different conclusions.” The message was that 9 Evenings should be judged more holistically and apart from critics’ reaction to individual performances.John Brockman, in the pages of The Village Voice, expressed a similar judgment.One goal of 9 Evenings was to give artists access to new technologies and engineering expertise. On this score, the event succeeded.

Other reviews appeared throughout 9 Evenings’ run at the Armory that took a similar line. John Gruen, who had initially supported the ambitious alliance between artists and engineers, called the opening night “dismal, dismaying…a flop and farce” exacerbated by delays and technical difficulties. For Patrick O’Connor, a dance writer for The Jersey Journal, the whole affair had the air of a big rip-off. Could you believe, he asked readers, that 1,500 people (i.e. suckers) had paid good money to get into 9 Evenings while another 1,500 were turned away? O’Connor knew “the big guns were out” when a “beautiful lady in a maroon and gray reversible raincoat” marched up to poet Allen Ginsberg and said “You probably don’t remember me but I’m Susan Sontag…More chic than that you can’t get.” He advised his culture-seeking Jersey readers to instead visit Manhattan’s Latin Quarter club where “the girls don’t even wear pasties anymore.”Not all reviews were knee-jerk negative or designed to discomfit. Brian O’Doherty’s lengthy post-mortem for the new magazine Art and Artists accurately judged 9 Evenings as being less about its two main ingredients, theatre and engineering. It was instead, he said, a “criss-cross of traditions, disciplines, time-streams, and audiences” which produced a “huge short-circuited tangle.” And, depending on which strand one followed – art, theatre, or technology i.e. the worlds of the artist or art critic versus that of the engineer – “you can end up with entirely different conclusions.” The message was that 9 Evenings should be judged more holistically and apart from critics’ reaction to individual performances.John Brockman, in the pages of The Village Voice, expressed a similar judgment.One goal of 9 Evenings was to give artists access to new technologies and engineering expertise. On this score, the event succeeded. However, a second hoped-for accomplishment was to generate a situation where artists could do something original and aesthetically pleasing with these new resources. Here, Brockman was less sanguine, laying blame with Klüver’s “rather worshipful attitude toward artists” which resulted in an “illusory collaboration.” This was, he observed, an ironic reversal of the usual situation where the artist is called upon to provide background images or sound for a production – say, a movie or television commercial – yet “has no basic say in the creative process.” If anything, Brockman argued for engineers to not just be technological enablers but instead step out of the background and become full creative partners.Not surprisingly, the negative reactions to 9 Evenings wounded Billy Klüver and some of his engineer colleagues, people he had personally recruited for the project. As Robby Robinson noted to an artist involved with 9 Evenings, "You guys are emotionally prepared for this [negative criticism]. We aren't." This is not to say that the bad reviews didn't affect the artists. But engineers from Bell Labs certainly weren't used to seeing their work critiqued in such a public way.After the final performance and well-into the organizational stages for his fledgling group Experiments in Art and Technology, Klüver responded with an essay for Artforum. Alternating between explanation and defensiveness, he asked, “Have you ever met a normal healthy, and working engineer who gives a damn about contemporary art?” One could, of course, wonder whether Artforum’s readers knew any engineers, healthy or otherwise. Klüver continued, “Why should the contemporary artist want to use technology and engineering as material?” 9 Evenings was an attempt to see what happened – it was an experiment – when you put these communities together. The point was not to showcase or explain the technology to the audience. If the performers or engineers had to explain the technology, then they would also be obliged to explain the art and this, one of his colleagues noted "was too reprehensible to consider.”Klüver’s managerial decision, of course, created a paradox. The people best positioned to explain the technical aspects of the performances were disinclined to do so. But when technical problems occurred – and Klüver insisted in Artforum that they were far less common than critics assumed – the engineers were held accountable. Added to this mix was “both an unfamiliarity with technology and a rather infantile expectation about technology as a ‘performer.’” Klüver ended his essay by needling Artforum’s readers with the mordant observation: “We had our best reviews in Electronic News and The Wall Street Journal.”Moreover, Klüver’s view of 9 Evenings as an experiment might best to be considered in terms of how researchers in science or engineering view such things. Failure and success are relative, with a good deal of knowledge to be learned from the former. Moreover, experiment entails risk. Klüver told artists involved with 9 Evenings that “at Bell Labs any scientist who didn’t have a 90% failure record on his experiments was not considered a good scientist.” Consequently, one can imagine a certain incommensurability between the evaluative criteria that 9 Evenings participants had – artists as well as engineers – versus those of art critics. These differing markers of what counted as success or failure would vex many other art and technology initiatives.As a collective reaction, critics’ responses to 9 Evenings fell into three general categories. One: artists’ efforts to integrate technology and engineering into their creations had failed. Two: the engineers’ technical malfunctions had failed the artists and, therefore, Art itself. Three: the whole experiment was a misguided effort. Even if the artists and engineers had been personally enriched by collaborating with one another, the audience didn’t get to share in the reward.I’d like to offer a different assessment. Think of 9 Evenings less as art or theatre or even as the dying gasp of the “Happenings” scene that New York artists had created. Throughout the 1960s, the wonders of aerospace and computer technologies were made manifest by all sorts of sophisticated advertising campaigns, as several recent books makes clear (such as this and this). These messages and accompanying imagery spoke directly to Americans’ sense of technological prowess.

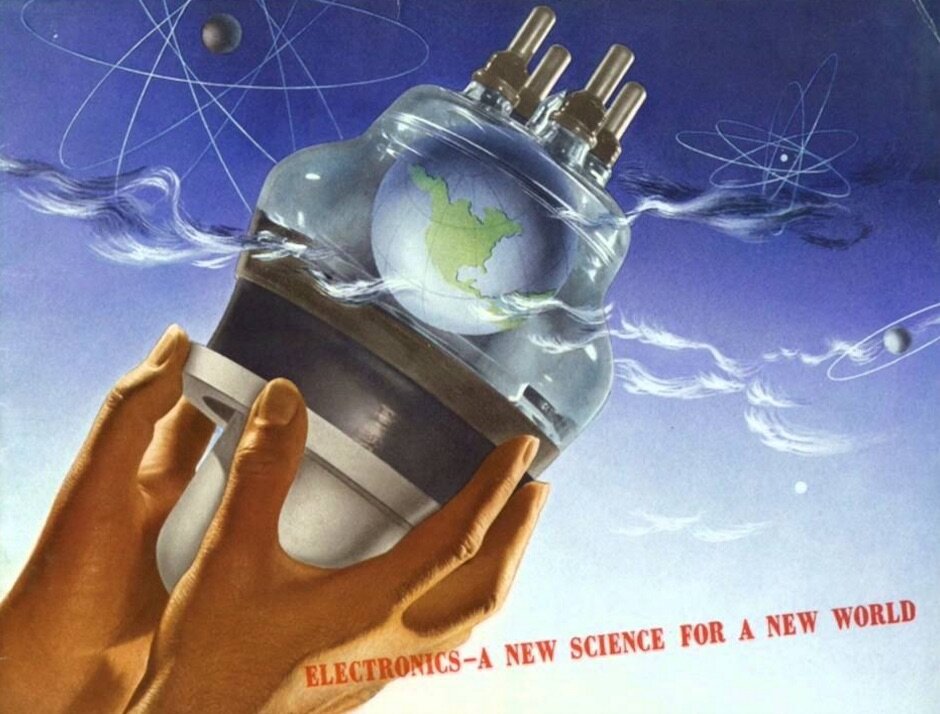

However, a second hoped-for accomplishment was to generate a situation where artists could do something original and aesthetically pleasing with these new resources. Here, Brockman was less sanguine, laying blame with Klüver’s “rather worshipful attitude toward artists” which resulted in an “illusory collaboration.” This was, he observed, an ironic reversal of the usual situation where the artist is called upon to provide background images or sound for a production – say, a movie or television commercial – yet “has no basic say in the creative process.” If anything, Brockman argued for engineers to not just be technological enablers but instead step out of the background and become full creative partners.Not surprisingly, the negative reactions to 9 Evenings wounded Billy Klüver and some of his engineer colleagues, people he had personally recruited for the project. As Robby Robinson noted to an artist involved with 9 Evenings, "You guys are emotionally prepared for this [negative criticism]. We aren't." This is not to say that the bad reviews didn't affect the artists. But engineers from Bell Labs certainly weren't used to seeing their work critiqued in such a public way.After the final performance and well-into the organizational stages for his fledgling group Experiments in Art and Technology, Klüver responded with an essay for Artforum. Alternating between explanation and defensiveness, he asked, “Have you ever met a normal healthy, and working engineer who gives a damn about contemporary art?” One could, of course, wonder whether Artforum’s readers knew any engineers, healthy or otherwise. Klüver continued, “Why should the contemporary artist want to use technology and engineering as material?” 9 Evenings was an attempt to see what happened – it was an experiment – when you put these communities together. The point was not to showcase or explain the technology to the audience. If the performers or engineers had to explain the technology, then they would also be obliged to explain the art and this, one of his colleagues noted "was too reprehensible to consider.”Klüver’s managerial decision, of course, created a paradox. The people best positioned to explain the technical aspects of the performances were disinclined to do so. But when technical problems occurred – and Klüver insisted in Artforum that they were far less common than critics assumed – the engineers were held accountable. Added to this mix was “both an unfamiliarity with technology and a rather infantile expectation about technology as a ‘performer.’” Klüver ended his essay by needling Artforum’s readers with the mordant observation: “We had our best reviews in Electronic News and The Wall Street Journal.”Moreover, Klüver’s view of 9 Evenings as an experiment might best to be considered in terms of how researchers in science or engineering view such things. Failure and success are relative, with a good deal of knowledge to be learned from the former. Moreover, experiment entails risk. Klüver told artists involved with 9 Evenings that “at Bell Labs any scientist who didn’t have a 90% failure record on his experiments was not considered a good scientist.” Consequently, one can imagine a certain incommensurability between the evaluative criteria that 9 Evenings participants had – artists as well as engineers – versus those of art critics. These differing markers of what counted as success or failure would vex many other art and technology initiatives.As a collective reaction, critics’ responses to 9 Evenings fell into three general categories. One: artists’ efforts to integrate technology and engineering into their creations had failed. Two: the engineers’ technical malfunctions had failed the artists and, therefore, Art itself. Three: the whole experiment was a misguided effort. Even if the artists and engineers had been personally enriched by collaborating with one another, the audience didn’t get to share in the reward.I’d like to offer a different assessment. Think of 9 Evenings less as art or theatre or even as the dying gasp of the “Happenings” scene that New York artists had created. Throughout the 1960s, the wonders of aerospace and computer technologies were made manifest by all sorts of sophisticated advertising campaigns, as several recent books makes clear (such as this and this). These messages and accompanying imagery spoke directly to Americans’ sense of technological prowess. The most spectacular of these, the American space program, was an international techno-spectacle that blended engineering, marketing, and performance. Only in failure could it meet or exceed the hype generated for it.

The most spectacular of these, the American space program, was an international techno-spectacle that blended engineering, marketing, and performance. Only in failure could it meet or exceed the hype generated for it. Like the grandeur and gigantism of Apollo, the bigness of 9 Evenings fed into critics' suspicion. In her diary notes about 9 Evenings, artist Simone Forti wrote that, “The artists decided to go big because it was more exciting and dangerous.” Their decision, she observed, was made “on an intuition that the work the artists will eventually want to have come out of this relationship will be big in scale, making full use of mass media and industrial resources.” This quest for scale and funding was redolent of 1960s-era Big Science projects, a style of activity artists were supposedly expected to steer clear of.Just as the American space program was never about “science” or even “engineering,” 9 Evenings was never about art per se. The corporate funding, defense-derived technology, and market strategizing that enabled it made it less of an ensemble of artists’ performances and more of what historian Daniel Boorstin called a “pseudo-event”. Audience members who came to witness 9 Evenings arrived already enmeshed in 1960s spectacle culture shaped by mass advertising, marketing, and public relations firms.While delays and technical problems diminished the impact of the performances at the Armory, it’s also reasonable to conclude that marketing of American technology in general, and 9 Evenings in particular, elevated audience and critics imaginings of what technology could do – Technology could win the war in Vietnam, cure Cancer, merge seamlessly with Art – to unrealizable heights. In the mid-1960s, the real marriage of art and engineering, as The New Yorker noted with the snide erudition one expects, was instead happening in the television studios where commercials were made. Like a primetime space shot, to its critics 9 Evenings was a media event that crashed and burned on the launch pad.Ironically, despite the harsh and perhaps premature judgment from art critics, audience members did get to see what was promised to them. Alex Hay broadcasted his body’s sounds, Robert Rauschenberg’s Open Score showed audience members what images made via infrared cameras looked like, and Lucinda Child’s piece Vehicle created the impression of dancers moving about while suspended on air. God bless American science.

Like the grandeur and gigantism of Apollo, the bigness of 9 Evenings fed into critics' suspicion. In her diary notes about 9 Evenings, artist Simone Forti wrote that, “The artists decided to go big because it was more exciting and dangerous.” Their decision, she observed, was made “on an intuition that the work the artists will eventually want to have come out of this relationship will be big in scale, making full use of mass media and industrial resources.” This quest for scale and funding was redolent of 1960s-era Big Science projects, a style of activity artists were supposedly expected to steer clear of.Just as the American space program was never about “science” or even “engineering,” 9 Evenings was never about art per se. The corporate funding, defense-derived technology, and market strategizing that enabled it made it less of an ensemble of artists’ performances and more of what historian Daniel Boorstin called a “pseudo-event”. Audience members who came to witness 9 Evenings arrived already enmeshed in 1960s spectacle culture shaped by mass advertising, marketing, and public relations firms.While delays and technical problems diminished the impact of the performances at the Armory, it’s also reasonable to conclude that marketing of American technology in general, and 9 Evenings in particular, elevated audience and critics imaginings of what technology could do – Technology could win the war in Vietnam, cure Cancer, merge seamlessly with Art – to unrealizable heights. In the mid-1960s, the real marriage of art and engineering, as The New Yorker noted with the snide erudition one expects, was instead happening in the television studios where commercials were made. Like a primetime space shot, to its critics 9 Evenings was a media event that crashed and burned on the launch pad.Ironically, despite the harsh and perhaps premature judgment from art critics, audience members did get to see what was promised to them. Alex Hay broadcasted his body’s sounds, Robert Rauschenberg’s Open Score showed audience members what images made via infrared cameras looked like, and Lucinda Child’s piece Vehicle created the impression of dancers moving about while suspended on air. God bless American science.