Engineering a Body Electric

“Fantasy, dreams, superhuman, science fiction…” – this was how artist Alex Hay described his ideas when first meeting with Billy Klüver and other engineers from Bell Labs. The occasion was a series of planning meetings for 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, a formative moment for the American art & technology movement. “I had ideas,” Hay told an interviewer 1966 about his interest in "machines that were going to move me about. A whole environment just for the purpose of the various ways to deal with the human body.”By the time Hay’s performance Grass Field debuted on October 13, 1966 – he performed it again nine days later on the next-to-last night of 9 Evenings – his interpretation of how the artist’s body and the environment could interact had transformed. This change was catalyzed by Hay’s intense and collaborative interactions with Klüver’s engineer colleagues from Bell Labs. The final version of Grass Field took advantage of medical research done decades earlier coupled with the latest in electronics technology that Bell engineers had access to. Alex Hay was born in east-central Florida in 1930. After graduating from Florida State University, Hay moved to New York City where he became part of the Judson Dance Theatre. This was a group of dancers, artists, and composers – all of them active in experimental and avant-garde art – active primarily between 1962 and 1964. Members included Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, Lucinda Child, Steve Paxton, and Hay’s partner Deborah, all of whom would participate with him in 9 Evenings at New York’s 69th Regiment Armory. ((Biographical sketches of all participants are here. Art historian Clarisse Bardiot has a wonderful and carefully researched multi-media exploration of 9 Evenings which I've profited from greatly.))

Alex Hay was born in east-central Florida in 1930. After graduating from Florida State University, Hay moved to New York City where he became part of the Judson Dance Theatre. This was a group of dancers, artists, and composers – all of them active in experimental and avant-garde art – active primarily between 1962 and 1964. Members included Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, Lucinda Child, Steve Paxton, and Hay’s partner Deborah, all of whom would participate with him in 9 Evenings at New York’s 69th Regiment Armory. ((Biographical sketches of all participants are here. Art historian Clarisse Bardiot has a wonderful and carefully researched multi-media exploration of 9 Evenings which I've profited from greatly.)) To understand the engineering that helped Alex Hay realize his artistic vision, we might work backwards, starting with the performance itself. Hay's notes for Grass Field list its three main elements: “Internal sound potential of the body; External body color; A singular work activity.” He wanted his body’s sounds – “brain waves, muscle activity, eye movement” – to be picked up, amplified, and “transmitted to a central control station” and the audience at the Armory. So far as a work activity – Hay’s piece called for the placement of dozens of numbered six foot squares of duck cloth in a regular pattern. These would then be “retrieved in a correct arithmetic progression” and re-stacked.Lucy Lippard, a young art critic who attended 9 Evenings described the scene. Hay appeared dressed in a “peach-flesh pyjama suit” wearing a backpack-sized amplifier. Methodically – too slowly for many in the audience – he laid out 100 squares of the same peach-colored cloth in a “modular pattern.” All the while, electrodes and amplifiers on Hay picked up and transmitted the sounds of his body, at work and then at rest.

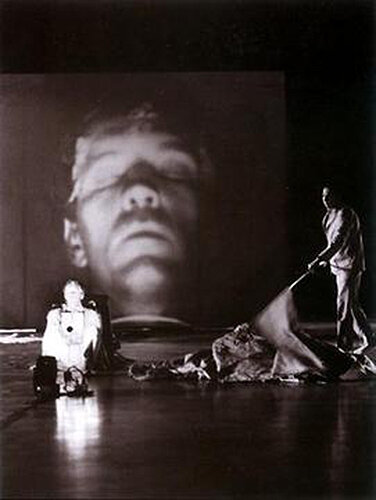

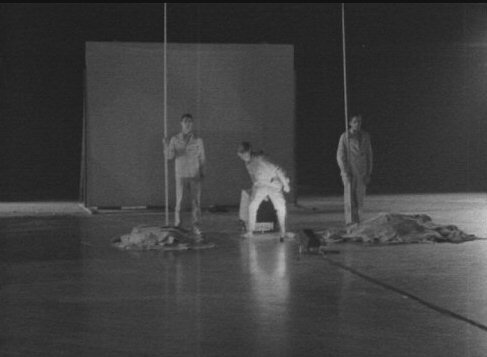

To understand the engineering that helped Alex Hay realize his artistic vision, we might work backwards, starting with the performance itself. Hay's notes for Grass Field list its three main elements: “Internal sound potential of the body; External body color; A singular work activity.” He wanted his body’s sounds – “brain waves, muscle activity, eye movement” – to be picked up, amplified, and “transmitted to a central control station” and the audience at the Armory. So far as a work activity – Hay’s piece called for the placement of dozens of numbered six foot squares of duck cloth in a regular pattern. These would then be “retrieved in a correct arithmetic progression” and re-stacked.Lucy Lippard, a young art critic who attended 9 Evenings described the scene. Hay appeared dressed in a “peach-flesh pyjama suit” wearing a backpack-sized amplifier. Methodically – too slowly for many in the audience – he laid out 100 squares of the same peach-colored cloth in a “modular pattern.” All the while, electrodes and amplifiers on Hay picked up and transmitted the sounds of his body, at work and then at rest. When finished, Hay say down in front of the audience and the lights dimmed. A giant screen behind him “projected a close-up image of his expressionless face” as he opened and closed his eyes. The projected image of his face created a link between Hay's physical activity - opening and closing his eyes - and the sounds that were generated by his body. Then, while Hay remained seated, Robert Rauschenberg and Steve Paxton – un-amplified – came out to pick up the squares one by one. Grass Field ended with the cloth pieces stacked in front of Hay and Rauschenberg and Paxton standing to either side of him.Hay's piece, according to newspaper articles from the time, left most audience members and critics baffled, if not hostile. The piece unfolded over more than 90 minutes and, in keeping with Klüver's injunction that the engineering details not intrude into or overshadow the art, audience members were unaware that the hisses, static, and booms they heard were coming from Hay's body. Many walked out. Andy Warhol was overheard to say, "I think it's just great."

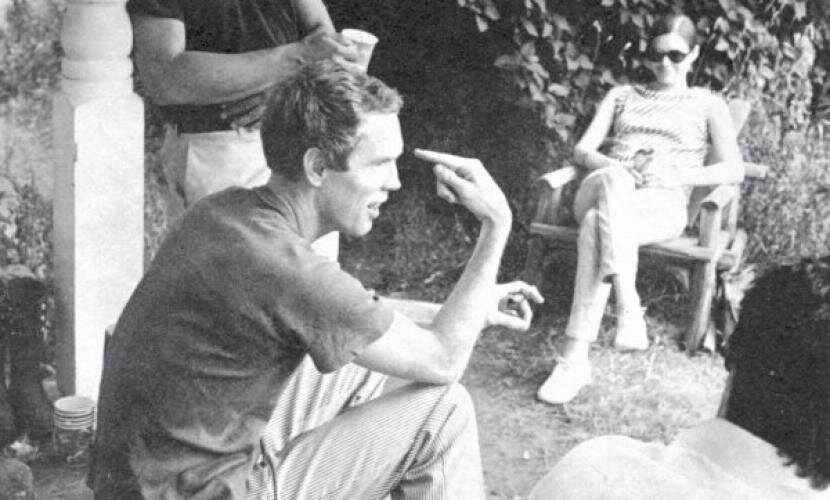

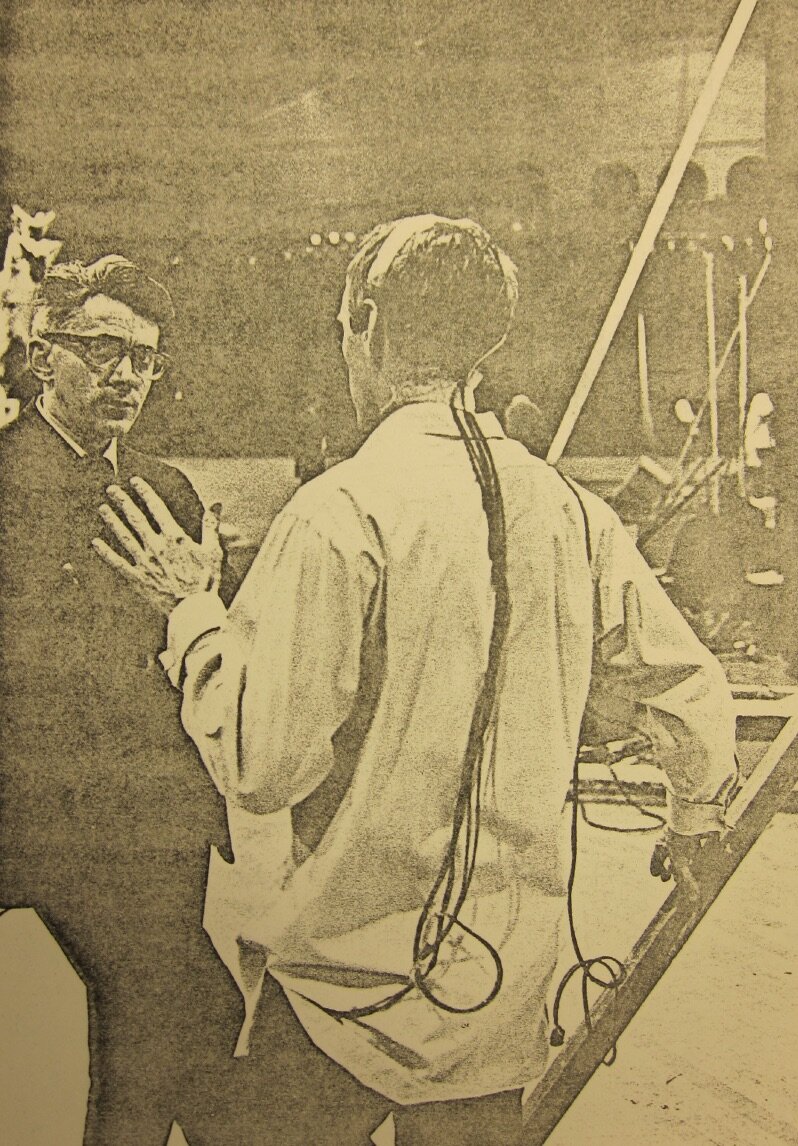

When finished, Hay say down in front of the audience and the lights dimmed. A giant screen behind him “projected a close-up image of his expressionless face” as he opened and closed his eyes. The projected image of his face created a link between Hay's physical activity - opening and closing his eyes - and the sounds that were generated by his body. Then, while Hay remained seated, Robert Rauschenberg and Steve Paxton – un-amplified – came out to pick up the squares one by one. Grass Field ended with the cloth pieces stacked in front of Hay and Rauschenberg and Paxton standing to either side of him.Hay's piece, according to newspaper articles from the time, left most audience members and critics baffled, if not hostile. The piece unfolded over more than 90 minutes and, in keeping with Klüver's injunction that the engineering details not intrude into or overshadow the art, audience members were unaware that the hisses, static, and booms they heard were coming from Hay's body. Many walked out. Andy Warhol was overheard to say, "I think it's just great." Although Grass Field's conceptualization was straightforward, its execution required very sophisticated engineering. Klüver, in a memo to his Bell colleagues, noted that the piece was “clear and simple” but “it looks as if there will be complicated technical problems.” L.J. (“Robby”) Robinson, an engineer at Bell who worked on wireless technology, recalled, “It was like preparing a man to go into space with the sensors attached to his body and the radio transmitters and amplifiers scattered over his body so they would not interfere with his movements.” A photo of Hay before his performance shows him chatting with composer David Tudor, wires running from his head and down his back.

Although Grass Field's conceptualization was straightforward, its execution required very sophisticated engineering. Klüver, in a memo to his Bell colleagues, noted that the piece was “clear and simple” but “it looks as if there will be complicated technical problems.” L.J. (“Robby”) Robinson, an engineer at Bell who worked on wireless technology, recalled, “It was like preparing a man to go into space with the sensors attached to his body and the radio transmitters and amplifiers scattered over his body so they would not interfere with his movements.” A photo of Hay before his performance shows him chatting with composer David Tudor, wires running from his head and down his back. Hay’s piece revolved around his desire to capture and amplify his body’s sounds and movements, essentially transforming his body into an instrument. “I want to pick up faint body sounds like brain waves, cardiac sounds, muscle sounds and amplify them,” he told an interviewer in September 1966. His activity would, meanwhile, alter their sound and tempo. The idea of monitoring the body’s electrical signals, especially those from the brain, was an old one. In 1924, German physiologist Hans Berger recorded the first human electroencephalograph and within a decade the EEG became a standard tool and laboratories and hospitals.The name Hay chose for his piece - Grass Field - was a play on words that wove in some interesting history of science. His performance made use of his body's electric fields, of course. "Grass" came from the name of the Grass Instrument Company, a Massachusetts-based company started in the 1930s that made EEG equipment. ((This information comes from Clarisse Bardiot's thorough exploration of Grass Field.))

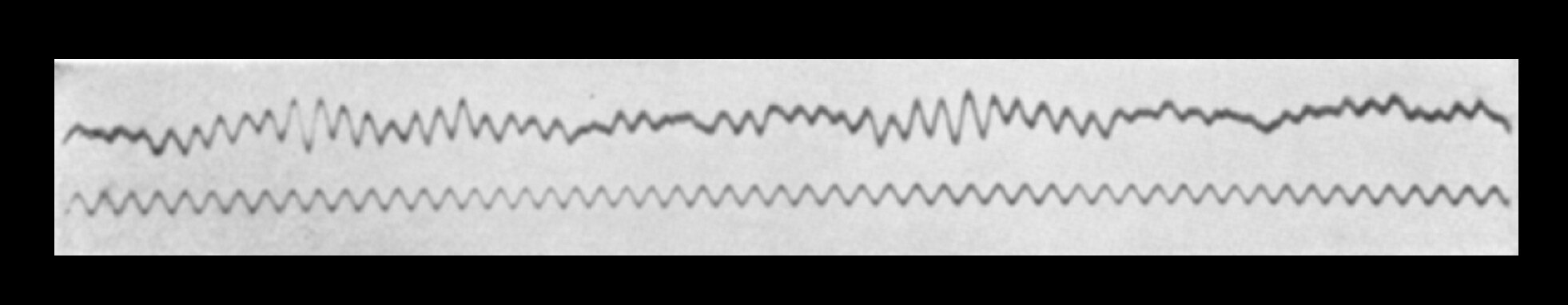

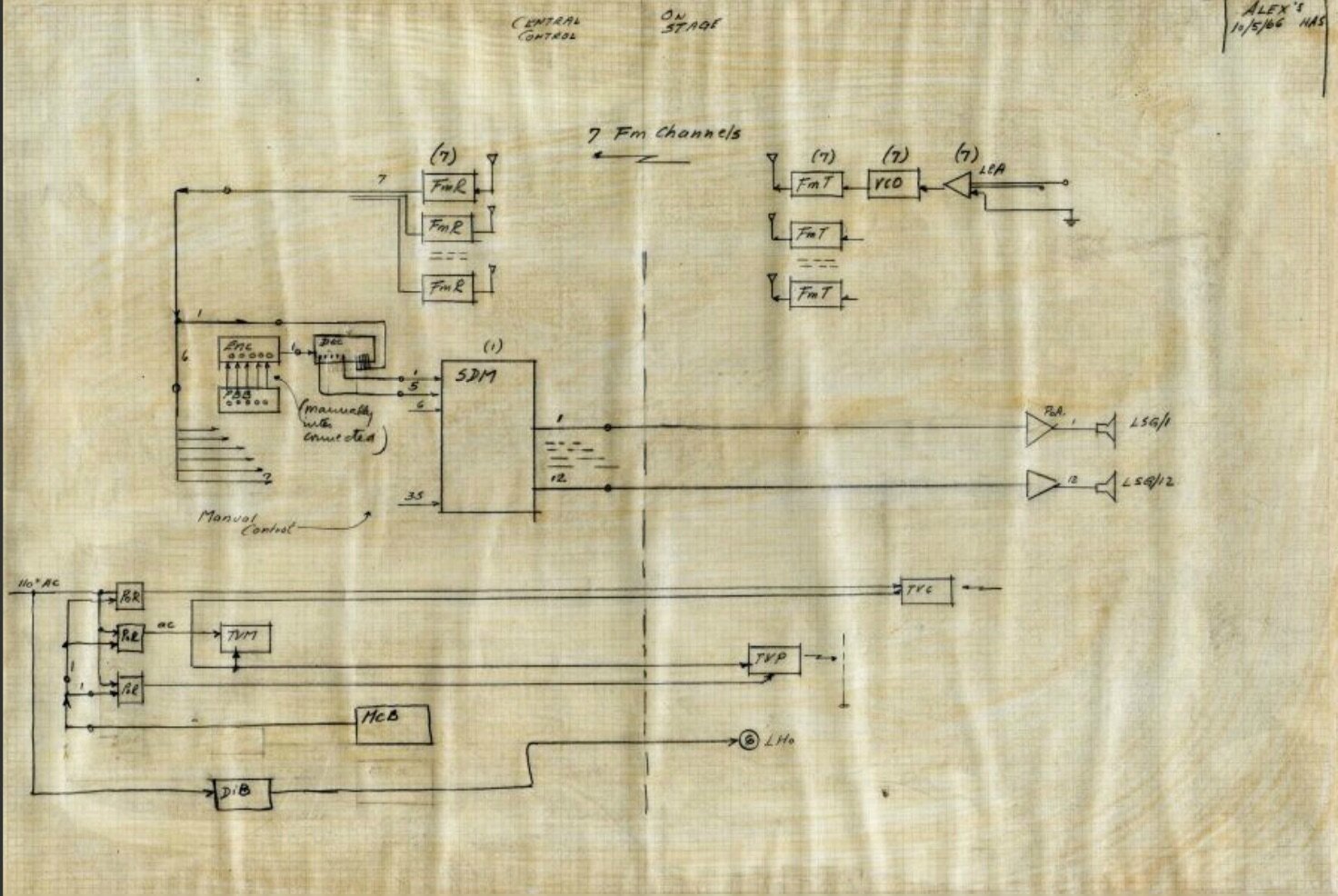

Hay’s piece revolved around his desire to capture and amplify his body’s sounds and movements, essentially transforming his body into an instrument. “I want to pick up faint body sounds like brain waves, cardiac sounds, muscle sounds and amplify them,” he told an interviewer in September 1966. His activity would, meanwhile, alter their sound and tempo. The idea of monitoring the body’s electrical signals, especially those from the brain, was an old one. In 1924, German physiologist Hans Berger recorded the first human electroencephalograph and within a decade the EEG became a standard tool and laboratories and hospitals.The name Hay chose for his piece - Grass Field - was a play on words that wove in some interesting history of science. His performance made use of his body's electric fields, of course. "Grass" came from the name of the Grass Instrument Company, a Massachusetts-based company started in the 1930s that made EEG equipment. ((This information comes from Clarisse Bardiot's thorough exploration of Grass Field.)) Two main challenges for the Bell engineers working with Hay were portability and power. As Hay noted, equipment for making encephalographs usually isn’t moving about. In addition, he needed batteries that were small and lightweight enough to carry yet could also power his gear. As part of the engineering research needed to realize Grass Field, Herb Schneider, the “performance engineer” for the piece, consulted doctors and EEG technicians at Mount Sinai Hospital and local medical companies.A key component for Hay was a series of differential amplifiers. Bell technicians Pete Cumminski and Marty Wazowicz designed and built several of these. These recorded Hay’s electrical signals from heart, brain, and eye muscles and amplified them. These signals were then sent to an FM wireless transmitter made by another Bell technician.

Two main challenges for the Bell engineers working with Hay were portability and power. As Hay noted, equipment for making encephalographs usually isn’t moving about. In addition, he needed batteries that were small and lightweight enough to carry yet could also power his gear. As part of the engineering research needed to realize Grass Field, Herb Schneider, the “performance engineer” for the piece, consulted doctors and EEG technicians at Mount Sinai Hospital and local medical companies.A key component for Hay was a series of differential amplifiers. Bell technicians Pete Cumminski and Marty Wazowicz designed and built several of these. These recorded Hay’s electrical signals from heart, brain, and eye muscles and amplified them. These signals were then sent to an FM wireless transmitter made by another Bell technician. This wasn’t the first time Bell staff had developed equipment that translated an artist’s movements into an electrical signal. In 1963, Billy Klüver and Harold Hodges helped dancer Yvonne Rainer realize a piece called At My Body’s House. They rigged a small wireless system – a microphone and transmitter – which could pick up the sounds of Rainer’s breathing as she danced.While Hay’s piece extended this idea, the equipment involved in 1966 was more complicated. At least four engineers contributed to Grass Field’s technology and Hay estimated that Robinson spent $1000 of his own money to buy equipment for for the piece.

This wasn’t the first time Bell staff had developed equipment that translated an artist’s movements into an electrical signal. In 1963, Billy Klüver and Harold Hodges helped dancer Yvonne Rainer realize a piece called At My Body’s House. They rigged a small wireless system – a microphone and transmitter – which could pick up the sounds of Rainer’s breathing as she danced.While Hay’s piece extended this idea, the equipment involved in 1966 was more complicated. At least four engineers contributed to Grass Field’s technology and Hay estimated that Robinson spent $1000 of his own money to buy equipment for for the piece. The technology for Alex Hay’s October 13 performance didn't work properly until the evening of the show. Robinson recalled that in the days leading up to 9 Evenings, Hay was "at the point of no return...no real breakthroughs had occurred to indicate a chance of things working.” Less than two weeks before opening night, the Bell engineers decided to risk a new approach, using integrated circuits, a relatively new technology at the time.About five days before 9 Evenings started, things started to come together, equipment-wise, but “that final bit of usable body noise just wouldn’t show up,” recalled Robinson. At this point, Herb Schneider and Bob Kieronski, a young Bell engineer who joined the effort, were working long hours, shuttling between the Armory and their day jobs at Bell’s laboratories in New Jersey.

The technology for Alex Hay’s October 13 performance didn't work properly until the evening of the show. Robinson recalled that in the days leading up to 9 Evenings, Hay was "at the point of no return...no real breakthroughs had occurred to indicate a chance of things working.” Less than two weeks before opening night, the Bell engineers decided to risk a new approach, using integrated circuits, a relatively new technology at the time.About five days before 9 Evenings started, things started to come together, equipment-wise, but “that final bit of usable body noise just wouldn’t show up,” recalled Robinson. At this point, Herb Schneider and Bob Kieronski, a young Bell engineer who joined the effort, were working long hours, shuttling between the Armory and their day jobs at Bell’s laboratories in New Jersey. The finished custom-made amplifiers didn't arrive until the night before the show. The engineers attached them to Hay’s body but the signals “would not stabilize and produce those elusive sounds of the body.” The group disbanded for the night and the general consensus was that Hay’s contribution to 9 Evenings would probably have to be canceled. Robinson and the other Bell engineers continued to troubleshoot the equipment throughout the next day. When Hay showed up at the Armory that evening he found, to his surprise, that hadn't been dropped from the show but, instead, he could generate “a beautiful set of sounds” for Grass Field.Hay’s views toward the engineers who made his piece possible changed markedly over the course of making Grass Field. He described one engineer as “pretty casual and apathetic” at the start but, as 9 Evenings drew closer, he was working long hours for free at the Armory. Nonetheless, Hay didn’t have any illusions that the engineers he collaborated with would become converts to avant-garde art. “Chances are,” he said, “they have very conventional ideas about art.” 9 Evenings wasn’t about turning engineers into artists but rather giving artists access to engineers – their expertise and their hardware – as a new and flexible material with which to work.

The finished custom-made amplifiers didn't arrive until the night before the show. The engineers attached them to Hay’s body but the signals “would not stabilize and produce those elusive sounds of the body.” The group disbanded for the night and the general consensus was that Hay’s contribution to 9 Evenings would probably have to be canceled. Robinson and the other Bell engineers continued to troubleshoot the equipment throughout the next day. When Hay showed up at the Armory that evening he found, to his surprise, that hadn't been dropped from the show but, instead, he could generate “a beautiful set of sounds” for Grass Field.Hay’s views toward the engineers who made his piece possible changed markedly over the course of making Grass Field. He described one engineer as “pretty casual and apathetic” at the start but, as 9 Evenings drew closer, he was working long hours for free at the Armory. Nonetheless, Hay didn’t have any illusions that the engineers he collaborated with would become converts to avant-garde art. “Chances are,” he said, “they have very conventional ideas about art.” 9 Evenings wasn’t about turning engineers into artists but rather giving artists access to engineers – their expertise and their hardware – as a new and flexible material with which to work. What interested the engineers that Hay and other artists in 9 Evenings interacted with was less about the artistic quality of the final product but the process involved in seeing it realized. This demanded attentive interaction with the artists – listening to what they wanted and finding ways to technologically translate their visions into devices and electrical systems. “Take a person where a product is dependent on their full participation,” Hay said of his engineer collaborators, “When full participation produces the product, they’re interested.”With Grass Field, Alex Hay’s electrified body became an instrument turned on by a group of people. With its focus on feedback - taking electric cues from Hay's body and transforming them into sounds in real-time, Grass Field stands as an example of the systems-and-cybernetic art that critics like Jack Burnham saw as harbingers of a new generation of art. Finally, we can imagine Hay's body and the collaborative processes it was enmeshed in as a site for communication between artists and engineers with the signals they generated radiating outward from the Armory to today.

What interested the engineers that Hay and other artists in 9 Evenings interacted with was less about the artistic quality of the final product but the process involved in seeing it realized. This demanded attentive interaction with the artists – listening to what they wanted and finding ways to technologically translate their visions into devices and electrical systems. “Take a person where a product is dependent on their full participation,” Hay said of his engineer collaborators, “When full participation produces the product, they’re interested.”With Grass Field, Alex Hay’s electrified body became an instrument turned on by a group of people. With its focus on feedback - taking electric cues from Hay's body and transforming them into sounds in real-time, Grass Field stands as an example of the systems-and-cybernetic art that critics like Jack Burnham saw as harbingers of a new generation of art. Finally, we can imagine Hay's body and the collaborative processes it was enmeshed in as a site for communication between artists and engineers with the signals they generated radiating outward from the Armory to today.