Of Geese, Gravity, and Subjective Science

Note: A few months ago, I wrote about Bishop Francis Godwin, his 1638 book The Man in the Moone, and the 17th century space race. What started me thinking about this was a series of art installations by the Berlin-based artist Agnes Meyer-Brandis. Since my new research project is exploring the art-science-technology interface, I decided to look further. This post is adapted from a forthcoming essay that will appear in the journal Leonardo.  On the first of August in 2008, there was a total solar eclipse in Novosibirsk in southwestern Siberia. Starting in the late afternoon, the moon slowly slipped in front of the sun. Normally invisible wisps of the solar corona came into view during the brief period of totality as did the planets Mercury and Venus.But in those few moments of darkness, something else was taking place. On a small island in the River Ob, 65 kilometers south of Novosibirsk, clad in protective gear akin to a hazmat suit, there was a person tethered to thirteen specially trained white geese arranged in a haphazard V-formation. When the eclipse arrived, the early evening sky glowed with a pale and eerie orange-red light. The geese became very calm. Blackness descended. And, for just a moment, the large white birds seemed to vanish from sight. Had they flown? If so – where?The whole scenario – the geese, the potential passenger, the instrumented chair – was orchestrated by a German installation artist named Agnes Meyer-Brandis. I first learned of her work in 2012 at a meeting in Berlin on "outer space and the end of utopia." I was really jet lagged and, when Meyer-Brandis began to describe her work, I first was very annoyed. "What kind of academic paper is this?" I thought. Then - almost simultaneously - all of the tired American academics (the Berliners, of course, knew the story) realized she was parodying the presentation of a research paper while showcasing her own work. The tension broke and the talk was the best part of the entire meeting.For years, Meyer-Brandis had been intrigued by the perceptions and realities around what calls “gravitational anomalies.” To investigate these, she founded an Institute for Art and Subjective Science at Berlin's decommissioned Tempelhof Airport. As the institute’s symbol, Meyer-Brandis adopted the same twin tools of Galilean gravitational investigation that Apollo 15 astronauts used on the moon in 1971 – a hammer and a feather.

On the first of August in 2008, there was a total solar eclipse in Novosibirsk in southwestern Siberia. Starting in the late afternoon, the moon slowly slipped in front of the sun. Normally invisible wisps of the solar corona came into view during the brief period of totality as did the planets Mercury and Venus.But in those few moments of darkness, something else was taking place. On a small island in the River Ob, 65 kilometers south of Novosibirsk, clad in protective gear akin to a hazmat suit, there was a person tethered to thirteen specially trained white geese arranged in a haphazard V-formation. When the eclipse arrived, the early evening sky glowed with a pale and eerie orange-red light. The geese became very calm. Blackness descended. And, for just a moment, the large white birds seemed to vanish from sight. Had they flown? If so – where?The whole scenario – the geese, the potential passenger, the instrumented chair – was orchestrated by a German installation artist named Agnes Meyer-Brandis. I first learned of her work in 2012 at a meeting in Berlin on "outer space and the end of utopia." I was really jet lagged and, when Meyer-Brandis began to describe her work, I first was very annoyed. "What kind of academic paper is this?" I thought. Then - almost simultaneously - all of the tired American academics (the Berliners, of course, knew the story) realized she was parodying the presentation of a research paper while showcasing her own work. The tension broke and the talk was the best part of the entire meeting.For years, Meyer-Brandis had been intrigued by the perceptions and realities around what calls “gravitational anomalies.” To investigate these, she founded an Institute for Art and Subjective Science at Berlin's decommissioned Tempelhof Airport. As the institute’s symbol, Meyer-Brandis adopted the same twin tools of Galilean gravitational investigation that Apollo 15 astronauts used on the moon in 1971 – a hammer and a feather. Meyer-Brandis' "Moon Geese" projects were originally inspired by her discovery of Bishop Francis Godwin's book. Godwin's book - arguably the first work of science fiction in English - centered on the experiences of a Domingo Gonsales who is flown to the moon by a special breed of geese.

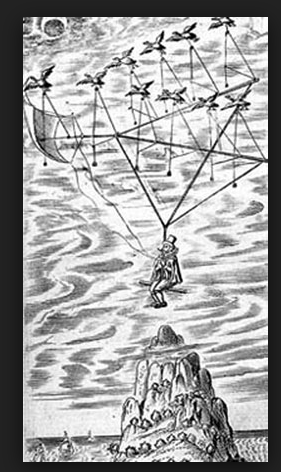

Meyer-Brandis' "Moon Geese" projects were originally inspired by her discovery of Bishop Francis Godwin's book. Godwin's book - arguably the first work of science fiction in English - centered on the experiences of a Domingo Gonsales who is flown to the moon by a special breed of geese. She decided to extend Godwin’s account as part of an exploration of what she called “subjective science.” These investigations – what will happen if I try this? what will I see? – drop exploratory probes into the working worlds of both the laboratory researcher and the studio artist. “I was wondering,” she said with mock seriousness, “if these cosmic phenomena would somehow influence the behavior of moon geese. Maybe they take off and fly to the moon with such a phenomenon?” ((Kadhim Shubber, “This German artist is training geese to fly to the moon,” Wired.UK, 9 September 2013))Faced with what she playfully labeled as “inconclusive results” in Siberia, Meyer-Brandis decided further experimentation was needed. Perhaps the problem rested with the birds. In 2011, Meyer-Brandis moved her project to Pollinaria, a village in east-central Italy, to launch an experiment of longer duration. Her Moon Goose Colony started with eleven new birds, each named after a spaceflight pioneer. ((THE MOON GOOSE ANALOGUE: Lunar Migration Bird Facility” by Agnes Meyer-Brandis was commissioned by The Arts Catalyst and FACT, in partnership with Pollinaria. „The Moon Goose Colony, P1“ is a Pollinaria project by Agnes Meyer-Brandis.)) It was a cosmopolitan flock. Besides Yuri, Neil, and Buzz, there was Valentina, for the first woman to go into space, Rakesh, named for the first Indian in space. And, of course, there was Gonsales.

She decided to extend Godwin’s account as part of an exploration of what she called “subjective science.” These investigations – what will happen if I try this? what will I see? – drop exploratory probes into the working worlds of both the laboratory researcher and the studio artist. “I was wondering,” she said with mock seriousness, “if these cosmic phenomena would somehow influence the behavior of moon geese. Maybe they take off and fly to the moon with such a phenomenon?” ((Kadhim Shubber, “This German artist is training geese to fly to the moon,” Wired.UK, 9 September 2013))Faced with what she playfully labeled as “inconclusive results” in Siberia, Meyer-Brandis decided further experimentation was needed. Perhaps the problem rested with the birds. In 2011, Meyer-Brandis moved her project to Pollinaria, a village in east-central Italy, to launch an experiment of longer duration. Her Moon Goose Colony started with eleven new birds, each named after a spaceflight pioneer. ((THE MOON GOOSE ANALOGUE: Lunar Migration Bird Facility” by Agnes Meyer-Brandis was commissioned by The Arts Catalyst and FACT, in partnership with Pollinaria. „The Moon Goose Colony, P1“ is a Pollinaria project by Agnes Meyer-Brandis.)) It was a cosmopolitan flock. Besides Yuri, Neil, and Buzz, there was Valentina, for the first woman to go into space, Rakesh, named for the first Indian in space. And, of course, there was Gonsales. Meyer-Brandis combined her interest in the peculiarities of gravity with forays into ethology and human-animal relations. As the Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz demonstrated in the 1930s – work that helped him win a share of a Nobel Prize in 1973 – newly hatched goslings imprint on their parents. Short films created by Meyer-Brandis show her flock trailing her everywhere and getting quite vocal in their distress when she took a short break. For me, the most haunting image from this experimentation is this:

Meyer-Brandis combined her interest in the peculiarities of gravity with forays into ethology and human-animal relations. As the Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz demonstrated in the 1930s – work that helped him win a share of a Nobel Prize in 1973 – newly hatched goslings imprint on their parents. Short films created by Meyer-Brandis show her flock trailing her everywhere and getting quite vocal in their distress when she took a short break. For me, the most haunting image from this experimentation is this: Training days were packed full of activities designed to foster their training as potential moon-bound gansas. A wooden rig similar to what Godwin described helped the geese learn the proper V-formation.

Training days were packed full of activities designed to foster their training as potential moon-bound gansas. A wooden rig similar to what Godwin described helped the geese learn the proper V-formation. Despite such resolute training, in the films Meyer-Brandis made, the presumed moon geese seem determined to remain earth-bound. More training was obviously needed. Therefore, she built a simulated lunar crater field at the newly christened “Pollinaria Institute of Technology.” Inspired by the Mars-500 mission, an international psychological experiment to simulate the isolation of long-term space travel, the “Moon Geese Analogue” (a video of this work - well-worth watching - is here) facility she built provides ample space for the geese to gain experience for the harsh lunar conditions they might one day encounter. Goose-made tracks in the dirt seem to mimic boot prints left by astronauts on the lunar surface. Only the availability of air, the lack of weightlessness, and ample bird droppings disturb the Moon Geese Analogue’s verisimilitude as a training platform.

Despite such resolute training, in the films Meyer-Brandis made, the presumed moon geese seem determined to remain earth-bound. More training was obviously needed. Therefore, she built a simulated lunar crater field at the newly christened “Pollinaria Institute of Technology.” Inspired by the Mars-500 mission, an international psychological experiment to simulate the isolation of long-term space travel, the “Moon Geese Analogue” (a video of this work - well-worth watching - is here) facility she built provides ample space for the geese to gain experience for the harsh lunar conditions they might one day encounter. Goose-made tracks in the dirt seem to mimic boot prints left by astronauts on the lunar surface. Only the availability of air, the lack of weightlessness, and ample bird droppings disturb the Moon Geese Analogue’s verisimilitude as a training platform. Human space voyagers, once launched into space, must maintain close communication with mission control. The Moon Goose Analogue Control Room, a portable installation Meyer-Brandis built, was opened to the public in 2012. Visitors could monitor the moongeese in real-time as they pecked and waddled across the simulated lunar surface hundreds of miles away at their training base in Italy. Internet communication channels provided two-way live video and audio feed between the Control Room and the Analogue. Telemetry showed data about the geese’s habitat and other experimental conditions.

Human space voyagers, once launched into space, must maintain close communication with mission control. The Moon Goose Analogue Control Room, a portable installation Meyer-Brandis built, was opened to the public in 2012. Visitors could monitor the moongeese in real-time as they pecked and waddled across the simulated lunar surface hundreds of miles away at their training base in Italy. Internet communication channels provided two-way live video and audio feed between the Control Room and the Analogue. Telemetry showed data about the geese’s habitat and other experimental conditions. Like Godwin’s The Man in the Moone, Meyer-Brandis’ “subjective science” experiments blend the playful with the probing. Separated by centuries, both Godwin and Meyer-Brandis have created a delicate yet durable alloy of artistic creativity and scientific inquiry.In questioning what is science and what is experience, Meyer-Brandis also forces a reconsideration of what an experiment – something done, after all, to test the boundary between known and the unknown – really is. With work inhabiting the subjunctive and the subjective, she maintains a serious composure broken only by a winking awareness that, unfortunately, moon geese don’t exist. But there is nothing dishonest in her presentation. The degree to which an observer believes depends on how much they appreciate the gravity of the experimenter’s working life. Like Bishop Godwin, she takes us on a fantastic voyage to a liminal space just beyond the boundaries of believability.

Like Godwin’s The Man in the Moone, Meyer-Brandis’ “subjective science” experiments blend the playful with the probing. Separated by centuries, both Godwin and Meyer-Brandis have created a delicate yet durable alloy of artistic creativity and scientific inquiry.In questioning what is science and what is experience, Meyer-Brandis also forces a reconsideration of what an experiment – something done, after all, to test the boundary between known and the unknown – really is. With work inhabiting the subjunctive and the subjective, she maintains a serious composure broken only by a winking awareness that, unfortunately, moon geese don’t exist. But there is nothing dishonest in her presentation. The degree to which an observer believes depends on how much they appreciate the gravity of the experimenter’s working life. Like Bishop Godwin, she takes us on a fantastic voyage to a liminal space just beyond the boundaries of believability.