Science (and Science History) for the Public

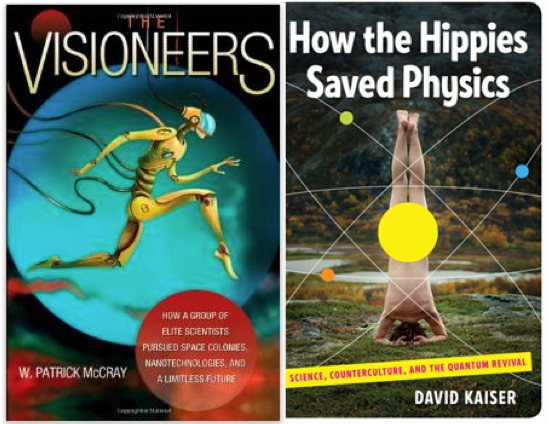

This past weekend, scholars met in Chicago for the annual meeting of the History of Science Society. A big highlight - for me at least - was that my book The Visioneers won the Watson Davis and Helen Miles Davis Prize which "promotes public understanding of the history of science."I was especially pleased to see that my book's award came on the heels of last year's winner, David Kaiser's romping How the Hippies Saved Physics. Given that a few of the same characters appear in both books, is it possible that HSS now stands for Hippie Studies Society. :) So, who were Watson and Helen Miles Davis? This question takes us to some interesting places in the history of how journalists, working with scientists, communicated new research discoveries to the general public. All of this activity unfolded against a backdrop of tremendous change, not just in science, but media technologies as well as public taste and expectations.Watson Davis and Helen Miles were both born in 1896. As a young man, Watson trained to be an engineer but also had an interest in bringing news about science to a wider audience.

This question takes us to some interesting places in the history of how journalists, working with scientists, communicated new research discoveries to the general public. All of this activity unfolded against a backdrop of tremendous change, not just in science, but media technologies as well as public taste and expectations.Watson Davis and Helen Miles were both born in 1896. As a young man, Watson trained to be an engineer but also had an interest in bringing news about science to a wider audience. In 1921, he was appointed Managing Editor of a new organization called Science Service. Now known as the Society for Science and the Public, Science Service was started that same year by journalist Edward W. Scripps and zoologist William Emerson Ritter. ((The creation of Science Service and its activities are documented wonderfully by historian Marcel LaFollette in a series of books.)) Its mission was to informed the public of the latest achievements in science. As Scripps said, their organization should "tell the millions outside the laboratories and the lecture halls what was going on inside." ((Quote from article.)) At the same time, the service had to be perceived not as a cheerleader for science but rather an objective and reliable source of information for the public and newspaper editors. These activities were largely funded by Scripps who donated $30,000 per year from 1921 until his death in 1926. His will put $500,000 in a trust for Science Service which provided an endowment for three more decades.Davis himself became director of Science Services in 1933, a position he held until 1966. He was married to Helen Miles (1896-1957) who herself was involved with science communication; she edited the journal Chemistry which the American Chemical Society published.The history of Science Service's and Davis's professional life gives a fascinating window into all sorts of important events throughout the mid-20th century, some connected with science, some not. These are all the more fascinating given the huge changes that took place within the scientific establishment and mass media industries during this time.

In 1921, he was appointed Managing Editor of a new organization called Science Service. Now known as the Society for Science and the Public, Science Service was started that same year by journalist Edward W. Scripps and zoologist William Emerson Ritter. ((The creation of Science Service and its activities are documented wonderfully by historian Marcel LaFollette in a series of books.)) Its mission was to informed the public of the latest achievements in science. As Scripps said, their organization should "tell the millions outside the laboratories and the lecture halls what was going on inside." ((Quote from article.)) At the same time, the service had to be perceived not as a cheerleader for science but rather an objective and reliable source of information for the public and newspaper editors. These activities were largely funded by Scripps who donated $30,000 per year from 1921 until his death in 1926. His will put $500,000 in a trust for Science Service which provided an endowment for three more decades.Davis himself became director of Science Services in 1933, a position he held until 1966. He was married to Helen Miles (1896-1957) who herself was involved with science communication; she edited the journal Chemistry which the American Chemical Society published.The history of Science Service's and Davis's professional life gives a fascinating window into all sorts of important events throughout the mid-20th century, some connected with science, some not. These are all the more fascinating given the huge changes that took place within the scientific establishment and mass media industries during this time. For example, Science Service provided extensive coverage of the 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial" in Dayton, Tennessee. Watson Davis went to Dayton to cover the proceedings. His photographs, as well as the official reports broadcast by Science Service, gave Americans a different sense of the controversy stirred by the "trial of the century" than they might otherwise have received from other news services. Two decades later, Science Service was one of the organs - along with the New York Times which had an inside scoop - that communicated the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the American public.Although initially intended as a news service, Science Service produced an extensive and sophisticated set of products that spanned several different forms of media. Besides These included radio programs, motion pictures, phonograph records, and science demonstration kits that would be distributed through the mail.Under Watson Davis's directorship, Science Services also organized science fairs. The first Science Talent Search (originally sponsored by Westinghouse and now sponsored by Intel since 1998), was held in 1942. The first two winners were Paul Teschan who went on do research in nephrology and Marina Prajmovsky who had a career as an ophthalmologist.

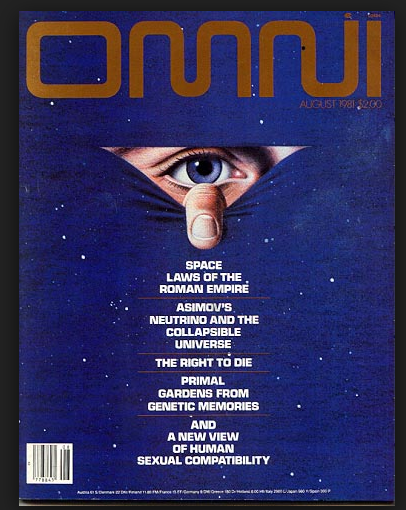

For example, Science Service provided extensive coverage of the 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial" in Dayton, Tennessee. Watson Davis went to Dayton to cover the proceedings. His photographs, as well as the official reports broadcast by Science Service, gave Americans a different sense of the controversy stirred by the "trial of the century" than they might otherwise have received from other news services. Two decades later, Science Service was one of the organs - along with the New York Times which had an inside scoop - that communicated the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the American public.Although initially intended as a news service, Science Service produced an extensive and sophisticated set of products that spanned several different forms of media. Besides These included radio programs, motion pictures, phonograph records, and science demonstration kits that would be distributed through the mail.Under Watson Davis's directorship, Science Services also organized science fairs. The first Science Talent Search (originally sponsored by Westinghouse and now sponsored by Intel since 1998), was held in 1942. The first two winners were Paul Teschan who went on do research in nephrology and Marina Prajmovsky who had a career as an ophthalmologist. During the Davis's career, science as well as the technologies of mass communication transformed. Science Service learned how to occupy a middle ground; it had to maintain enough public appeal (and, sometimes, sensationalism) to newspaper editors and radio hosts while not alienating the scientists and engineers who valued accuracy. During Davis's tenure, the entire scientific enterprise in the U.S. transformed. Big Science, secrecy, and massive government-funded laboratories became the norm while science and scientists became newsworthy. New fields like cosmology, nuclear physics, and molecular biology became prominent while older ways of doing and funding research faded. When Davis started his career, newsprint was king and radio was just starting; both were becoming rapidly commercialized. By the time of his death in 1967, televised news dominated.Science Service occupied a curious position in the science/reporting/public ecosystem of the mid-20th century. It was a not-for-profit independent news organization yet its goal was to promote understanding of science in a way that would not offend scientists yet would also appeal to publishers who bought its products. As Marcel LaFollette writes, Watson Davis's appointment as Science Service's director in 1933 was a "compromise that placed public interest and marketplace appeal first" but also responded to public demand for more stories about technological innovation while still, of course, attending to scientists’ concerns about accuracy.It's interesting to juxtapose the output of Science Service with other later ventures aimed to connect science and scientists with a broader audience. In the late 1970s, for example, there was a veritable boom in popular science. Dozens of new science and technology magazines, newspaper sections, and TV shows about science and technology appeared. One of the more curious critters to emerge was Omni magazine.

During the Davis's career, science as well as the technologies of mass communication transformed. Science Service learned how to occupy a middle ground; it had to maintain enough public appeal (and, sometimes, sensationalism) to newspaper editors and radio hosts while not alienating the scientists and engineers who valued accuracy. During Davis's tenure, the entire scientific enterprise in the U.S. transformed. Big Science, secrecy, and massive government-funded laboratories became the norm while science and scientists became newsworthy. New fields like cosmology, nuclear physics, and molecular biology became prominent while older ways of doing and funding research faded. When Davis started his career, newsprint was king and radio was just starting; both were becoming rapidly commercialized. By the time of his death in 1967, televised news dominated.Science Service occupied a curious position in the science/reporting/public ecosystem of the mid-20th century. It was a not-for-profit independent news organization yet its goal was to promote understanding of science in a way that would not offend scientists yet would also appeal to publishers who bought its products. As Marcel LaFollette writes, Watson Davis's appointment as Science Service's director in 1933 was a "compromise that placed public interest and marketplace appeal first" but also responded to public demand for more stories about technological innovation while still, of course, attending to scientists’ concerns about accuracy.It's interesting to juxtapose the output of Science Service with other later ventures aimed to connect science and scientists with a broader audience. In the late 1970s, for example, there was a veritable boom in popular science. Dozens of new science and technology magazines, newspaper sections, and TV shows about science and technology appeared. One of the more curious critters to emerge was Omni magazine. Omni wasn’t a direct competitor to “establishment” publications like Scientific American or shows like NOVA but existed in a class of its own. Instead it was more of a “para-scientific” publication that reported on recent developments in science and technology but for a non-elite audience. Besides presenting popular science discoveries, Omni crossed borders into areas - the paranormal, fringe science, and fantasy - that more mainstream magazines like Scientific American wouldn’t touch. Like the Science Service, Omni was part of a longer trend of science communication efforts shaped in varying degrees by entertainment values.Watson Davis and Science Service mastered the art of productive compromise - giving the public an engaging presentation while still maintaining respect for accuracy. As Davis wrote in 1960, "science is news, good news...that can compete...with crime, politics, human comedy and pathos." At the same time, it could be "written popularly so as to be accurate in fact and implication and yet be good reading." ((Watson Davis, "The Rise of Science Understanding," in Smithsonian Archives)) I'm proud to see Visioneers recognized with the Davis Prize.

Omni wasn’t a direct competitor to “establishment” publications like Scientific American or shows like NOVA but existed in a class of its own. Instead it was more of a “para-scientific” publication that reported on recent developments in science and technology but for a non-elite audience. Besides presenting popular science discoveries, Omni crossed borders into areas - the paranormal, fringe science, and fantasy - that more mainstream magazines like Scientific American wouldn’t touch. Like the Science Service, Omni was part of a longer trend of science communication efforts shaped in varying degrees by entertainment values.Watson Davis and Science Service mastered the art of productive compromise - giving the public an engaging presentation while still maintaining respect for accuracy. As Davis wrote in 1960, "science is news, good news...that can compete...with crime, politics, human comedy and pathos." At the same time, it could be "written popularly so as to be accurate in fact and implication and yet be good reading." ((Watson Davis, "The Rise of Science Understanding," in Smithsonian Archives)) I'm proud to see Visioneers recognized with the Davis Prize.