Taking It To The People

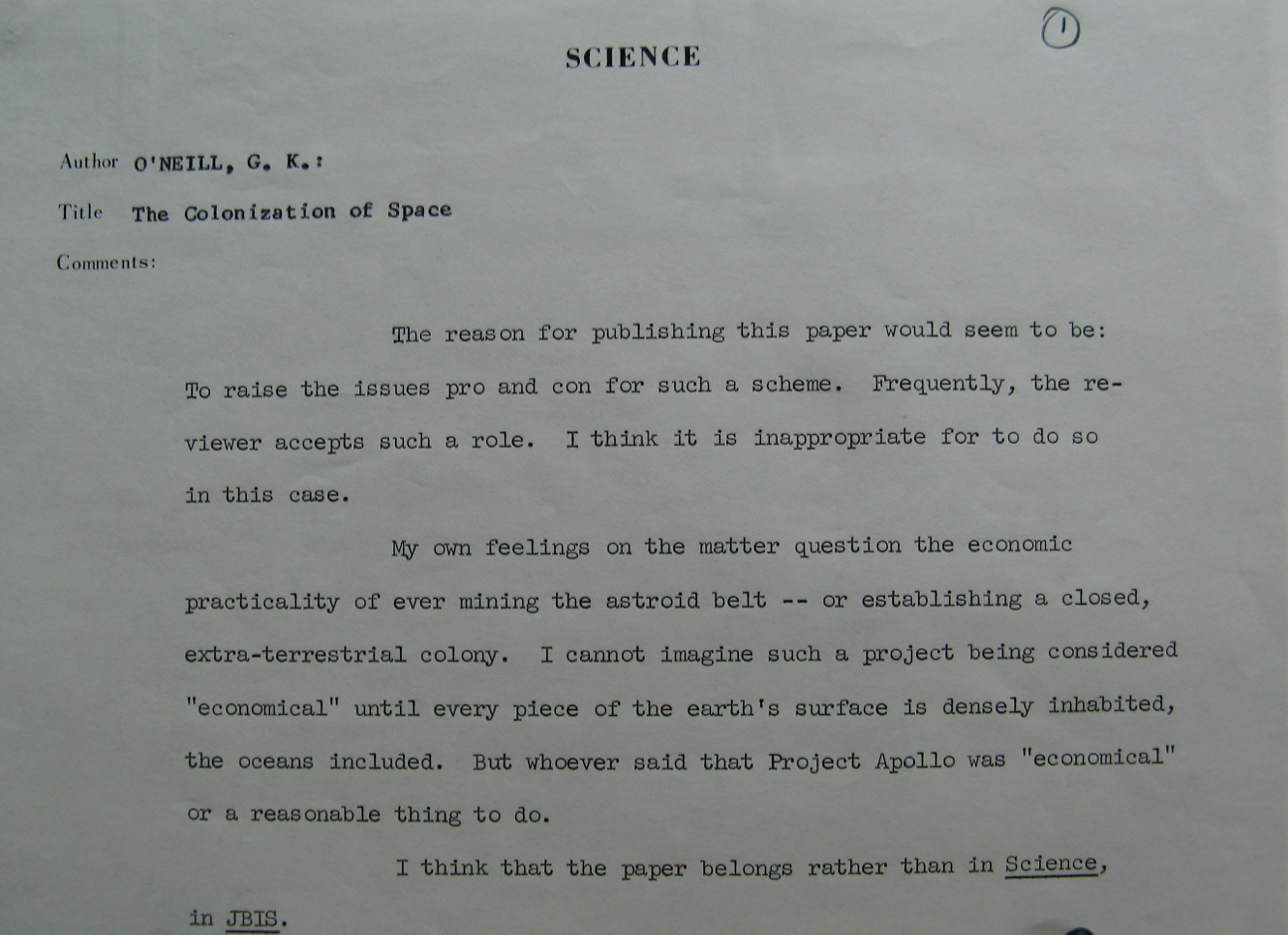

My favorite chapter in Gerard O'Neill’s 1977 book The High Frontier is actually the book’s appendix. Titled “Taking It To The People,” O'Neill described the difficulties (and eventual successes) he experienced when he tried to get attention from the public and his colleagues about his visioneering for space colonies.I commented on this chapter of O'Neill’s book obliquely in an earlier post which was about the challenges of defending one’s radical ideas once they’ve entered general circulation. I was reminded again of O'Neill’s “public engagement” efforts after a couple of professional experiences I had recently. I’ll come back to these shortly…After first striking out with Scientific American and then with The Atlantic Monthly, O'Neill tried to get his ideas before a wider audience via the journal Science, the flagship publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. This too was a bust. One of the anonymous comments acknowledged that “frequently” it is the reviewer's job to help sort out the “pros and cons for such” radical schemes.

My favorite chapter in Gerard O'Neill’s 1977 book The High Frontier is actually the book’s appendix. Titled “Taking It To The People,” O'Neill described the difficulties (and eventual successes) he experienced when he tried to get attention from the public and his colleagues about his visioneering for space colonies.I commented on this chapter of O'Neill’s book obliquely in an earlier post which was about the challenges of defending one’s radical ideas once they’ve entered general circulation. I was reminded again of O'Neill’s “public engagement” efforts after a couple of professional experiences I had recently. I’ll come back to these shortly…After first striking out with Scientific American and then with The Atlantic Monthly, O'Neill tried to get his ideas before a wider audience via the journal Science, the flagship publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. This too was a bust. One of the anonymous comments acknowledged that “frequently” it is the reviewer's job to help sort out the “pros and cons for such” radical schemes. Whether space colonies were a practical idea was one issue; the peer-reviewer also questioned the “economic practicality” of O'Neill’s ideas. A second anonymous reader asked whether O'Neill has succeeded in reaching "beyond purely technical questions” so as to address “special and delicate human aspects” (emphasis in original). This is somewhat ironic because O'Neill imagined that settlements and manufacturing based in space might provide the energy and resources needed for an expanding human civilization while moving environmental degradation that industrial activities caused off-planet.It’s interesting to juxtapose O'Neill’s focus with themes found in Matt Wisnioski’s new book Engineers for Change. Wisnioski sets much of his story at almost exactly the same time – c. 1970 – as O'Neill is starting to advocate his ideas for the “humanization of space.” Although O'Neill was trained as a high-energy physicist, he was very much at home among large scale engineering projects. Before getting hooked on space, he worked throughout the 1950s and 1960s on improving the design of particle accelerators. His personal concerns around 1970 reflect those of the engineers described in Wisnioski’s book.At Princeton University, O'Neill was well-aware of prevailing skepticism toward science and technology among his students. Despite the successes of the space program, advances in computer technology, and the Green Revolution, campus attitudes, O’Neill recalled, reflected widespread “disenchantment with the sciences” and a “revulsion against authority and against technology.” ((From p. 233 of Gerard K. O'Neill, The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1977)) Even the best students studying for science or engineering careers, O'Neill observed, seemed defensive, worried about being “accused by their colleagues of being irrelevant” or becoming cogs in the military-industrial complex.But what is interesting is that both Science referees found themselves pulled, like others who would debate the concept throughout the 1970s, between technical feasibility and broader questions of politics, economics, and societal needs. Just because a space colony could be built didn’t mean that it should be built. In other words, O'Neill was critiqued less for his speculative engineering and more for failing to more adequately consider its social dimensions. The concerns of Science’s referees aligned with the general “social turn” that many scientists and engineers took as the war in Vietnam continued, debates about the military-industrial complex intensified, et al..

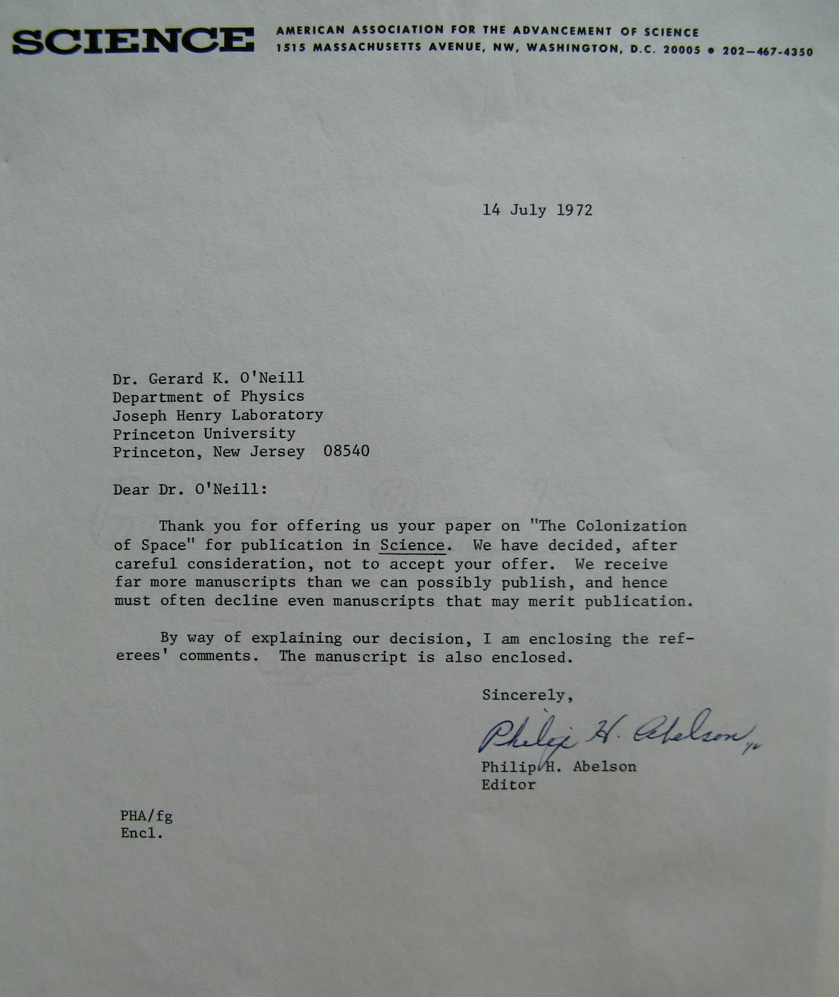

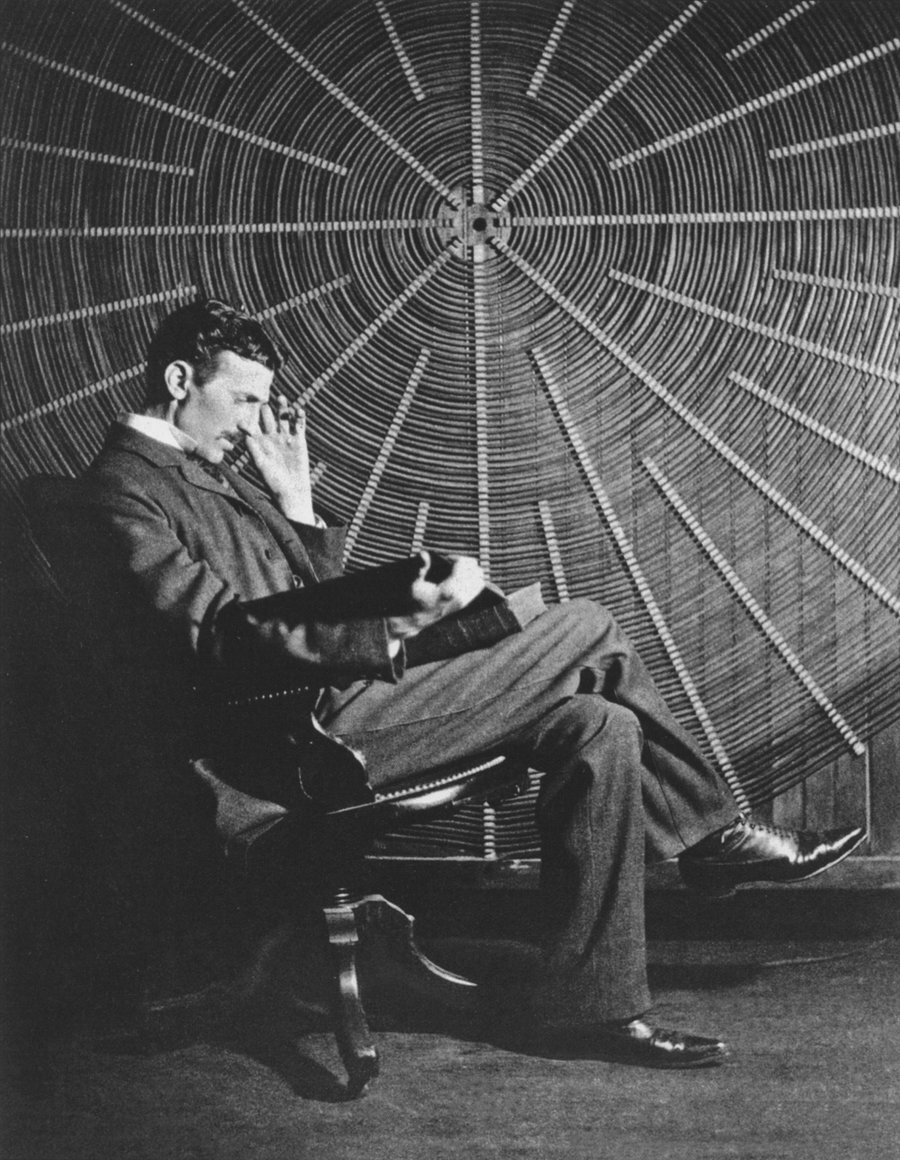

Whether space colonies were a practical idea was one issue; the peer-reviewer also questioned the “economic practicality” of O'Neill’s ideas. A second anonymous reader asked whether O'Neill has succeeded in reaching "beyond purely technical questions” so as to address “special and delicate human aspects” (emphasis in original). This is somewhat ironic because O'Neill imagined that settlements and manufacturing based in space might provide the energy and resources needed for an expanding human civilization while moving environmental degradation that industrial activities caused off-planet.It’s interesting to juxtapose O'Neill’s focus with themes found in Matt Wisnioski’s new book Engineers for Change. Wisnioski sets much of his story at almost exactly the same time – c. 1970 – as O'Neill is starting to advocate his ideas for the “humanization of space.” Although O'Neill was trained as a high-energy physicist, he was very much at home among large scale engineering projects. Before getting hooked on space, he worked throughout the 1950s and 1960s on improving the design of particle accelerators. His personal concerns around 1970 reflect those of the engineers described in Wisnioski’s book.At Princeton University, O'Neill was well-aware of prevailing skepticism toward science and technology among his students. Despite the successes of the space program, advances in computer technology, and the Green Revolution, campus attitudes, O’Neill recalled, reflected widespread “disenchantment with the sciences” and a “revulsion against authority and against technology.” ((From p. 233 of Gerard K. O'Neill, The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1977)) Even the best students studying for science or engineering careers, O'Neill observed, seemed defensive, worried about being “accused by their colleagues of being irrelevant” or becoming cogs in the military-industrial complex.But what is interesting is that both Science referees found themselves pulled, like others who would debate the concept throughout the 1970s, between technical feasibility and broader questions of politics, economics, and societal needs. Just because a space colony could be built didn’t mean that it should be built. In other words, O'Neill was critiqued less for his speculative engineering and more for failing to more adequately consider its social dimensions. The concerns of Science’s referees aligned with the general “social turn” that many scientists and engineers took as the war in Vietnam continued, debates about the military-industrial complex intensified, et al.. Ultimately, Science rejected O'Neill’s manuscript. Two years later, Physics Today published a revised version of it but the experience taught O'Neill that “taking it to the people” wasn’t easy.…which loops us back to my own experience. I’m in the midst of giving a series of public talks based on my Visioneers book. I’ve also been fortunate to have been asked to do some radio interviews and other media appearances. It’s been fun so far. For example, I recently gave a public talk at Caltech as part of the Skeptics Society's ‘Distinguished Lecture Series.’ About 100 people took time from a beautiful sunny SoCal afternoon (and the NFL playoffs) to hear me talk in dark auditorium; several hundred more tuned in over the web.)I was a little nervous because the Society is, well, skeptical. I thought they might take issue with the ideas actors in my book championed. This turned out not to be the case – they grokked that my book isn’t about adjudicating whether visioneers’ plans for the future were correct or wrong-headed. What concerns me more is how people like O'Neill conceived of and presented their ideas in response to the dire warnings in reports like Limits to Growth. What were their motives, hopes, and results? How did other technological communities react to their plans? How were these ideas brought to the public by journalists, science fiction writers, and popular culture?The questions and comments people had for me after the talk (and subsequent dinner chat at Burger Continental, thanks to Michael Shermer) took a few new turns. One group wanted to know “who else was a visioneer?” This is a pretty standard question and it's a fun one to kick around. I suggested that, according to my definition, Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace might qualify, Nikola Tesla was a definite “yes” and so were Doug Engelbart and Elon Musk. (What we didn't to was adequately discuss why there are so few women on the list. I bring this up in my book...but, I wish I had a more satisfying explanation other than to propose that this reflects the larger historical experiences of women in science and engineering careers. I'd be interested to hear from folks who might have more insights.)

Ultimately, Science rejected O'Neill’s manuscript. Two years later, Physics Today published a revised version of it but the experience taught O'Neill that “taking it to the people” wasn’t easy.…which loops us back to my own experience. I’m in the midst of giving a series of public talks based on my Visioneers book. I’ve also been fortunate to have been asked to do some radio interviews and other media appearances. It’s been fun so far. For example, I recently gave a public talk at Caltech as part of the Skeptics Society's ‘Distinguished Lecture Series.’ About 100 people took time from a beautiful sunny SoCal afternoon (and the NFL playoffs) to hear me talk in dark auditorium; several hundred more tuned in over the web.)I was a little nervous because the Society is, well, skeptical. I thought they might take issue with the ideas actors in my book championed. This turned out not to be the case – they grokked that my book isn’t about adjudicating whether visioneers’ plans for the future were correct or wrong-headed. What concerns me more is how people like O'Neill conceived of and presented their ideas in response to the dire warnings in reports like Limits to Growth. What were their motives, hopes, and results? How did other technological communities react to their plans? How were these ideas brought to the public by journalists, science fiction writers, and popular culture?The questions and comments people had for me after the talk (and subsequent dinner chat at Burger Continental, thanks to Michael Shermer) took a few new turns. One group wanted to know “who else was a visioneer?” This is a pretty standard question and it's a fun one to kick around. I suggested that, according to my definition, Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace might qualify, Nikola Tesla was a definite “yes” and so were Doug Engelbart and Elon Musk. (What we didn't to was adequately discuss why there are so few women on the list. I bring this up in my book...but, I wish I had a more satisfying explanation other than to propose that this reflects the larger historical experiences of women in science and engineering careers. I'd be interested to hear from folks who might have more insights.) One person insisted that Steve Jobs should make the list – I demurred with the proviso that perhaps the hybrid combo of Jobs+Woz had the right mix. (This person's insistence reminded me of how visioneers, as I’ve presented them, worked hard to maintain a certain purity of their ideas…I had to work pretty hard to make the case that I wasn’t anti-Jobs but that I just didn’t see him having the necessary technical chops to fit the category as I've defined it).But I what surprised me more than anything was the reaction from one person that I was being too hard on the visioneers by underestimating what they achieved. This was surprising because if anything, reaction from some of my history colleagues (those who don't study science or technology) tends to trend in the opposite direction ((This usually occurs while visiting the faculty mail room i.e. "Space colonies? We don't have them...so, how is that important? And nanotechnology? What's it done for us lately?" I don't usually point out that their on-going yet surely definitive study of 19th century dust collecting is pretty esoteric too.))However, the best part of the Skeptics talk was talking with someone about what my story would look like outside the non-U.S. context. “Were there,” he asked, “similar pro=space visioneer types in, say, the Soviet Union?” This was a great question. I’ve always wished that I had the materials and evidence that might give me a sense of what similar sort of things were happening in other countries. Maybe this stuff is out there. My own experience working just in the U.S. context tells me getting access would be tough – I had to track down lots of my research materials not just in archives but in people’s basements and airport storage lockers. Doing this in the former Soviet Union or France just wasn’t possible. But it was a great question.I’m giving several more talks in the next 6 weeks – Seattle, DC, Phoenix, and San Jose, so far. (This, combined with a full teaching schedule, means fewer Leaping Robot postings for awhile...) Somewhere along the way, I’ll come back to this topic of “taking it to the people” and see I can identify any larger patterns in terms of – apologies to Raymond Carver – what people talk about when they talk about the future.

One person insisted that Steve Jobs should make the list – I demurred with the proviso that perhaps the hybrid combo of Jobs+Woz had the right mix. (This person's insistence reminded me of how visioneers, as I’ve presented them, worked hard to maintain a certain purity of their ideas…I had to work pretty hard to make the case that I wasn’t anti-Jobs but that I just didn’t see him having the necessary technical chops to fit the category as I've defined it).But I what surprised me more than anything was the reaction from one person that I was being too hard on the visioneers by underestimating what they achieved. This was surprising because if anything, reaction from some of my history colleagues (those who don't study science or technology) tends to trend in the opposite direction ((This usually occurs while visiting the faculty mail room i.e. "Space colonies? We don't have them...so, how is that important? And nanotechnology? What's it done for us lately?" I don't usually point out that their on-going yet surely definitive study of 19th century dust collecting is pretty esoteric too.))However, the best part of the Skeptics talk was talking with someone about what my story would look like outside the non-U.S. context. “Were there,” he asked, “similar pro=space visioneer types in, say, the Soviet Union?” This was a great question. I’ve always wished that I had the materials and evidence that might give me a sense of what similar sort of things were happening in other countries. Maybe this stuff is out there. My own experience working just in the U.S. context tells me getting access would be tough – I had to track down lots of my research materials not just in archives but in people’s basements and airport storage lockers. Doing this in the former Soviet Union or France just wasn’t possible. But it was a great question.I’m giving several more talks in the next 6 weeks – Seattle, DC, Phoenix, and San Jose, so far. (This, combined with a full teaching schedule, means fewer Leaping Robot postings for awhile...) Somewhere along the way, I’ll come back to this topic of “taking it to the people” and see I can identify any larger patterns in terms of – apologies to Raymond Carver – what people talk about when they talk about the future.