Calling Governor Moonbeam?

The recent news that California is slowly scratching its way back from the budgetary abyss the state was circling the past three years delighted me for at least two reasons. One is obvious – I work for the University of California which had the proverbial stuffing beaten out of it during the Great Recession. My other source of joy is more esoteric.When the New York Times reported on Governor Edmund “Jerry” Brown’s recent State of the State speech, it noted in passing that as Democrats “face pressure to increase spending, many are now describing Mr. Brown, long known as ‘Governor Moonbeam’ for his eccentricities, as the only adult in the room.”As I describe at the end of The Visioneers, 1973 and 2013 are a lot closer than their four decades separation might suggest. A person who fell asleep in 1973 with The Limits to Growth on their lap and then woke up today would find today’s headlines eerily familiar. We have soaring oil prices, shortages of key minerals, and the birth of Spaceship Earth’s 7 billionth inhabitant. In response to dire expectations, so-called “doomsters” have suggested the need for restraints and restrictions, ideas which their “boomster” counterparts resist. More locally (for me) Jerry Brown is again/still leading the Golden State. And journalists are still tagging him with the “Moonbeam” label.Why Moonbeam? Readers of Leaping Robot past a certain age will know that this moniker was bestowed on Brown by Chicago columnist Mike Royko in 1976. Royko was referring to the fact that Brown’s 70s-era political appeal was mainly to the “moonbeam vote” by which he meant the “young, idealistic, and nontraditional.” Royko, circa 1976, had no great fondness for California, once calling it the “world’s largest outdoor mental asylum.” A few years later, he expanded on this, with a description any naturalist would appreciate: “If it babbles and its eyeballs are glazed it probably comes from California.” Royko’s tag for Brown stuck and it certainly damaged the California governor when he ran for president in 1980. But he later regretted the effect his words had, calling “Moonbeam” an “idiotic, damn-fool, meaningless, throw-away line” and asked people to stop tarring Brown with it. “Enough of this ‘Moonbeam’ stuff,” Mr. Royko concluded in 1991, “I declare it null, void and deceased.”But there is a little more to the Moonbeam story. Royko wasn’t just referring to Californians’ predisposition to perhaps being a little more free and easy going than Chicagoans. In the mid-1970s, Gov. Brown actually was quite spacey...In 1977, Brown became quite interested in Gerard O'Neill’s ideas for an expanded human presence in space. Besides noticing the swell of public interest, Brown was also mindful that the aerospace companies (and technology-oriented firms, in general) were a mainstay of the California economy. Brown had recently asked former Apollo astronaut Russell Schweickart to be his science advisor and he first met O’Neill at meetings facilitated by former Whole Earth Catalog publisher (and informal Brown advisor) Stewart Brand.In August 1977, as the movie Star Wars sold out theaters nationwide, Brand, Schweickart, and O’Neill and some 1,100 invited guests from the aerospace and science communities met at the Museum of Science and Industry in Los Angeles for the first California Space Day. The event blended O'Neill’s techno-utopianism with presentations from major aerospace firms. Space Day’s motto, emblazoned behind the podium, was anti-limits, proclaiming “California in the Space Age: An Era of Possibilities.” A working model of O'Neill’s mass driver device, which would soon be featured in an episode of the PBS science show Nova, sat next to the podium. Timothy Leary, meanwhile, pushed his psychedelic version of O'Neill’s vision, saying, “Now there is nowhere left for smart Americans to go but out into high orbit. I love that phrase – high orbit…We were talking about high orbit long before the space program.”Brown’s speech at Space Day abandoned his earlier ascetic language of limits and restricted opportunity which he had used at his 1975 inauguration.

Royko’s tag for Brown stuck and it certainly damaged the California governor when he ran for president in 1980. But he later regretted the effect his words had, calling “Moonbeam” an “idiotic, damn-fool, meaningless, throw-away line” and asked people to stop tarring Brown with it. “Enough of this ‘Moonbeam’ stuff,” Mr. Royko concluded in 1991, “I declare it null, void and deceased.”But there is a little more to the Moonbeam story. Royko wasn’t just referring to Californians’ predisposition to perhaps being a little more free and easy going than Chicagoans. In the mid-1970s, Gov. Brown actually was quite spacey...In 1977, Brown became quite interested in Gerard O'Neill’s ideas for an expanded human presence in space. Besides noticing the swell of public interest, Brown was also mindful that the aerospace companies (and technology-oriented firms, in general) were a mainstay of the California economy. Brown had recently asked former Apollo astronaut Russell Schweickart to be his science advisor and he first met O’Neill at meetings facilitated by former Whole Earth Catalog publisher (and informal Brown advisor) Stewart Brand.In August 1977, as the movie Star Wars sold out theaters nationwide, Brand, Schweickart, and O’Neill and some 1,100 invited guests from the aerospace and science communities met at the Museum of Science and Industry in Los Angeles for the first California Space Day. The event blended O'Neill’s techno-utopianism with presentations from major aerospace firms. Space Day’s motto, emblazoned behind the podium, was anti-limits, proclaiming “California in the Space Age: An Era of Possibilities.” A working model of O'Neill’s mass driver device, which would soon be featured in an episode of the PBS science show Nova, sat next to the podium. Timothy Leary, meanwhile, pushed his psychedelic version of O'Neill’s vision, saying, “Now there is nowhere left for smart Americans to go but out into high orbit. I love that phrase – high orbit…We were talking about high orbit long before the space program.”Brown’s speech at Space Day abandoned his earlier ascetic language of limits and restricted opportunity which he had used at his 1975 inauguration. “It is a world of limits but through respecting and reverencing the limits, endless possibilities emerge,” he said, “As for space colonies, it’s not a question of whether – only when and how.” The pro-space ideas Brown put forth were drawn straight from O'Neill’s vision – solar power beamed to earth via satellite, and space manufacturing facilities along with space settlements providing a “safety valve of unexplored frontiers” to accommodate the dreamers and rebels from the pro-space movement. Journalists, of course, noticed the gubernatorial shift in rhetorical direction and wondered if critics would “challenge what appears to be his recantation of Buddhist economics.” Outside, meanwhile, laid-off workers waved signs that said “Jobs on Earth, Not in Space."

“It is a world of limits but through respecting and reverencing the limits, endless possibilities emerge,” he said, “As for space colonies, it’s not a question of whether – only when and how.” The pro-space ideas Brown put forth were drawn straight from O'Neill’s vision – solar power beamed to earth via satellite, and space manufacturing facilities along with space settlements providing a “safety valve of unexplored frontiers” to accommodate the dreamers and rebels from the pro-space movement. Journalists, of course, noticed the gubernatorial shift in rhetorical direction and wondered if critics would “challenge what appears to be his recantation of Buddhist economics.” Outside, meanwhile, laid-off workers waved signs that said “Jobs on Earth, Not in Space."

Even after the klieg lights had been turned off at Space Day, Brown continued to push for a “California Space Program.” Brown, prompted by Schweickart, Brand, and O'Neill, was interested in making space socially useful and economically relevant. For example, Brown imagined that satellite communications would facilitate teaching and the exchange of research information between University of California campuses.

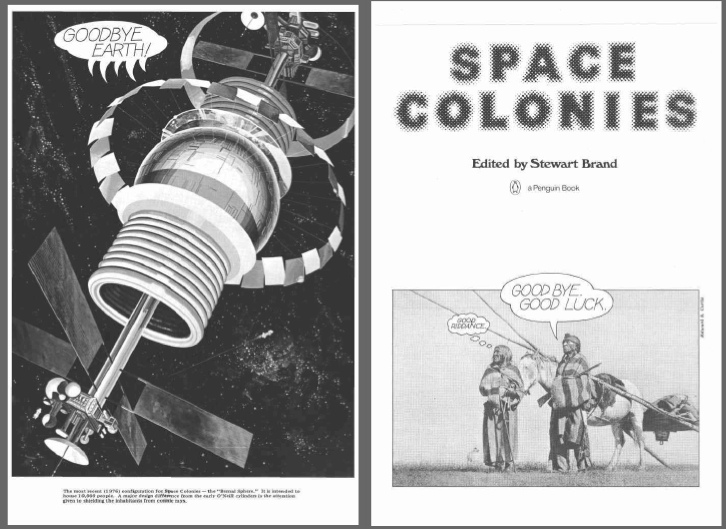

Such a satellite could also foster better emergency communications – nice for a state regularly wracked by fires, mudslides, and riots. Another usage Brown imagined was a system of space-based environmentally monitoring stations. Brown’s interest in prosaic uses of space was a far cry from the utopian-tinged visions of O'Neill. But both men were interested in seeing space exploration expand into areas that might more directly benefit people earth-side and also make some steps towards ameliorating environmental problems. As Brown 1980 campaign slogan had it: "protect the earth, serve the people and explore the universe." (I'd love to see someone run for office today with this!)Not everyone agreed with this vision of the future. Many pundits and writers - Lewis Mumford, John Holt, Wendell Berry - attacked O'Neill, Brand, and Brown for championing more "mega-projects" that would help support the military-industrial complex. Others blasted their claims that the humanization of space offered any real solutions to the earth's environmental problems. This debate was captured nicely in the opening pages of the 1977 book Space Coloniesthat Brand edited - one one page is a picture of a floating space colony. On the other page is a reproduction of a 19th century photo of a Native American couple - he says "Goodbye! Good luck!" while she grumbles "Good riddance!"So far, in his second lap as California's governor, Brown hasn't put forth any spacey ideas. Perhaps he learned his lesson the first time. Or, more likely, space just isn't the compelling technological frontier that it once was. Brown's take? “Moonbeam also stands for not being the insider,” said Mr. Brown. “But standing apart and marching to my own drummer. And I've done that.” I wonder what Mike Royko would say to all this...today's Brown sure seems less Moonbeamy but also a lot less dreamy.

This debate was captured nicely in the opening pages of the 1977 book Space Coloniesthat Brand edited - one one page is a picture of a floating space colony. On the other page is a reproduction of a 19th century photo of a Native American couple - he says "Goodbye! Good luck!" while she grumbles "Good riddance!"So far, in his second lap as California's governor, Brown hasn't put forth any spacey ideas. Perhaps he learned his lesson the first time. Or, more likely, space just isn't the compelling technological frontier that it once was. Brown's take? “Moonbeam also stands for not being the insider,” said Mr. Brown. “But standing apart and marching to my own drummer. And I've done that.” I wonder what Mike Royko would say to all this...today's Brown sure seems less Moonbeamy but also a lot less dreamy.