The Engineer as Work of Art

In August 1966, when Life magazine reported on the burgeoning art and technology scene, it highlighted the role of Johan Wilhelm “Billy” Klüver. According to the article, the 38-year-old engineer was “the Edison-Tesla-Steinmetz-Marconi-Leonardo da Vinci of the American avant-garde.” Besides working as a researcher at Bell Labs, Klüver had already collaborated with major artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, helping them incorporate electrical technologies into art pieces. His skill, explained Grace Glueck, an art writer for the New York Times a year earlier, “goes into friends’ creations. Klüver's contributions transcended the technical, however. As Life noted, the engineer was also engaged in developing a “scientific brain trust” in which engineers would assist artists in achieving their aesthetic vision. Where the artist has “an immediate, intuitive way of working” the engineer “proceeds logically and slowly toward an end.” Although “no visionary about life,” the engineer could, Klüver claimed, stimulate the artist with “new ways of looking at technology.”The first product from this mélange, Life said, would be a Festival for Art and Technology scheduled for the fall of 1966. Held at the 69th Regiment Armory – site of the famous 1913 exhibition of modern art – in mid-October 1966, this plan was realized as 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering.Unfolding, as it name suggests, over nine nights, the event stands out now as the coming out party of the art and technology movement in the United States. It also marked Klüver as the movement’s most visible and vocal spokesperson.Acting less as engineer or artist, Klüver was an orchestrator, a facilitator who wanted to bring artists and engineers together as an experiment to see what happened. The focus was not on the product – “We’re not interested in art,” Klüver told one writer in 1968 – but rather on the process that generated it. If we conflate process with a transitional act of becoming, changing, and seeing through experiment, than we can start to Klüver’s own career as a product of this – the “engineer as a work of art,” as an Art in America interview described him. Because of his pivotal role in coordinating 9 Evenings, I want to spend some time writing about the early experiences and influences that helped shape Klüver views toward art, technology, and the places where they overlapped.Klüver’s earliest contacts with the art world happened far away from the downtown New York art scene. Born in 1927 in Monaco, Klüver’s parents soon relocated back to their native Scandinavia and he grew up in Sweden where his father operated a tourist resort near the Norwegian border.

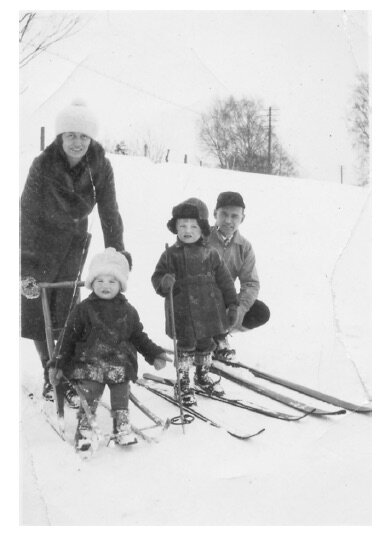

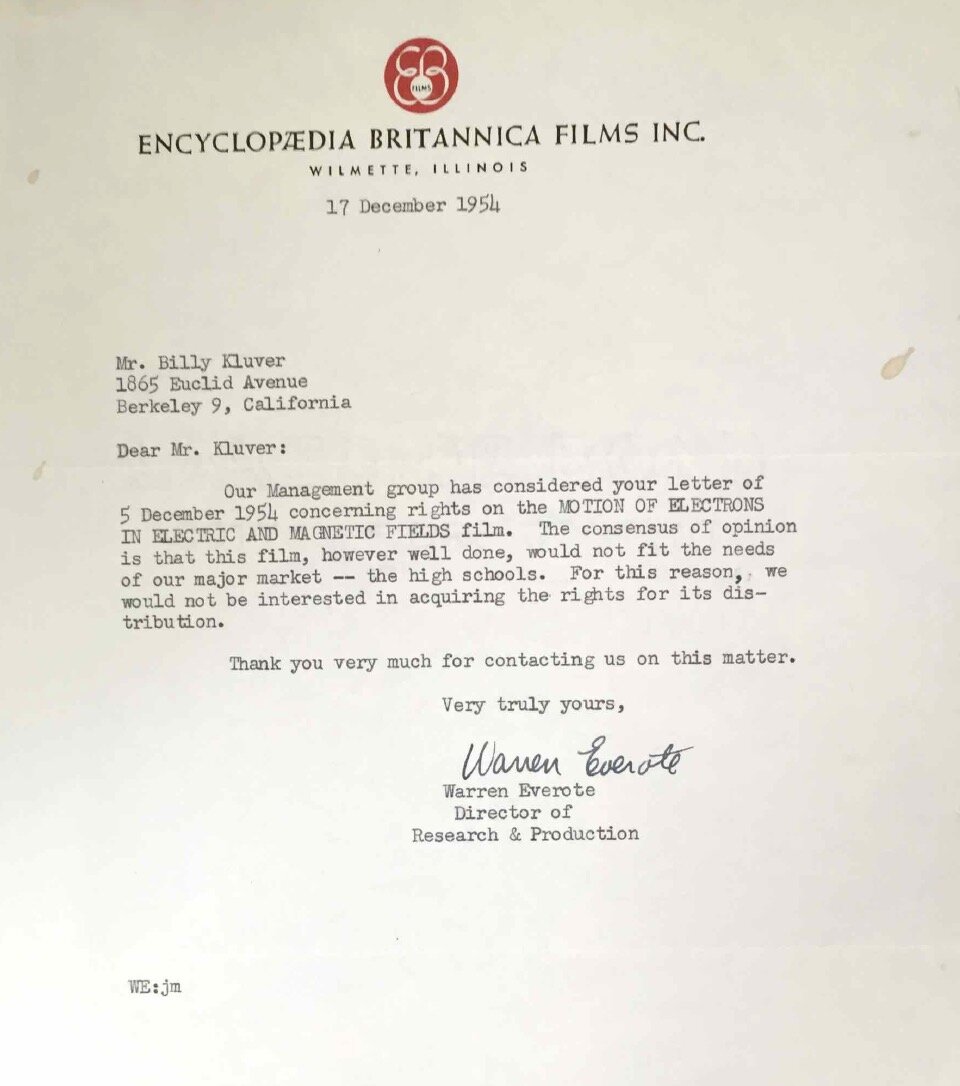

Klüver's contributions transcended the technical, however. As Life noted, the engineer was also engaged in developing a “scientific brain trust” in which engineers would assist artists in achieving their aesthetic vision. Where the artist has “an immediate, intuitive way of working” the engineer “proceeds logically and slowly toward an end.” Although “no visionary about life,” the engineer could, Klüver claimed, stimulate the artist with “new ways of looking at technology.”The first product from this mélange, Life said, would be a Festival for Art and Technology scheduled for the fall of 1966. Held at the 69th Regiment Armory – site of the famous 1913 exhibition of modern art – in mid-October 1966, this plan was realized as 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering.Unfolding, as it name suggests, over nine nights, the event stands out now as the coming out party of the art and technology movement in the United States. It also marked Klüver as the movement’s most visible and vocal spokesperson.Acting less as engineer or artist, Klüver was an orchestrator, a facilitator who wanted to bring artists and engineers together as an experiment to see what happened. The focus was not on the product – “We’re not interested in art,” Klüver told one writer in 1968 – but rather on the process that generated it. If we conflate process with a transitional act of becoming, changing, and seeing through experiment, than we can start to Klüver’s own career as a product of this – the “engineer as a work of art,” as an Art in America interview described him. Because of his pivotal role in coordinating 9 Evenings, I want to spend some time writing about the early experiences and influences that helped shape Klüver views toward art, technology, and the places where they overlapped.Klüver’s earliest contacts with the art world happened far away from the downtown New York art scene. Born in 1927 in Monaco, Klüver’s parents soon relocated back to their native Scandinavia and he grew up in Sweden where his father operated a tourist resort near the Norwegian border. After his parents divorced, Klüver moved with his mother to Stockholm where film became his consuming interest. Taking advantages of Stockholm’s vibrant film culture, the young Klüver joined the city’s University Film Society, a membership he maintained when he started his undergraduate coursework in 1946 at the Royal Institute of Technology. (Klüver’s autobiographical notes devote much more time discussing the film scene in Sweden and the movies he saw than his own interest in science and technology.)While in Stockholm, Klüver met Pontus Hultén. This proved an important connection as Hultén, a few years older than Klüver, later became the director of Stockholm’s Moderna Museet and, in the 1970s, the Centre Georges Pompidou. Hultén was a key contact for Klüver in the modern art world and, once he was working at Bell Labs, Klüver acted as a liaison for his fellow Swede to the American art scene.At university in Stockholm, Klüver’s electronics professor was Hannes Alfvén. Originally trained as a power engineer, Alfvén’s specialty was the study of plasma physics. Being in Sweden, one can imagine the draw that the Northern Lights had a research topic and, from the 1930s onward, he studied the aurorae borealis as a case study in the relationship between plasma movement in the presence of electrical and magnetic fields. This research brought Alfvén a share of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics. As Klüver recalled, Alfvén was a great role model, teaching him that “a physicist did not have to be limited in his interests or pursuits.” Writing with a pseudonym – Olaf Johannesson – Alfvén also wrote science fiction.Convinced that film could be an effective teaching tool, Klüver produced an animated short film that helped students visualize Alfvén’s laboratory research. Years later, when he came to the United States, Klüver brought copies of The Motion of Electrons in Electric and Magnetic Fields with him in the hope – unrealized – that Encyclopedia Britannica might be interested in it and others like it as a tool for teaching science.

After his parents divorced, Klüver moved with his mother to Stockholm where film became his consuming interest. Taking advantages of Stockholm’s vibrant film culture, the young Klüver joined the city’s University Film Society, a membership he maintained when he started his undergraduate coursework in 1946 at the Royal Institute of Technology. (Klüver’s autobiographical notes devote much more time discussing the film scene in Sweden and the movies he saw than his own interest in science and technology.)While in Stockholm, Klüver met Pontus Hultén. This proved an important connection as Hultén, a few years older than Klüver, later became the director of Stockholm’s Moderna Museet and, in the 1970s, the Centre Georges Pompidou. Hultén was a key contact for Klüver in the modern art world and, once he was working at Bell Labs, Klüver acted as a liaison for his fellow Swede to the American art scene.At university in Stockholm, Klüver’s electronics professor was Hannes Alfvén. Originally trained as a power engineer, Alfvén’s specialty was the study of plasma physics. Being in Sweden, one can imagine the draw that the Northern Lights had a research topic and, from the 1930s onward, he studied the aurorae borealis as a case study in the relationship between plasma movement in the presence of electrical and magnetic fields. This research brought Alfvén a share of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics. As Klüver recalled, Alfvén was a great role model, teaching him that “a physicist did not have to be limited in his interests or pursuits.” Writing with a pseudonym – Olaf Johannesson – Alfvén also wrote science fiction.Convinced that film could be an effective teaching tool, Klüver produced an animated short film that helped students visualize Alfvén’s laboratory research. Years later, when he came to the United States, Klüver brought copies of The Motion of Electrons in Electric and Magnetic Fields with him in the hope – unrealized – that Encyclopedia Britannica might be interested in it and others like it as a tool for teaching science. In 1951, Klüver graduated from the Royal Institute of Technology with a degree in electrical engineering. Before coming to the United States to continue his education, he worked at a Paris lab – a branch of Thomson CSF – which had a contract to build an underwater television camera for Jacques Cousteau. Cue Wes Anderson…In Marseilles, Klüver introduced himself to Cousteau as a “willing worker.” As he recalled, the French diver and science popularizer felt Klüver’s arms before inviting him to join the crew of Calypso. He spent that summer helping the crew recover materials from ancient Greek shipwreck off the French Riviera coast.A year later, Klüver was enrolled in the Ph.D. program at Berkeley’s Electrical Engineering Department. The three years it took him to finish his degree was a process Klüver referred to several times as boring and intellectually stifling.

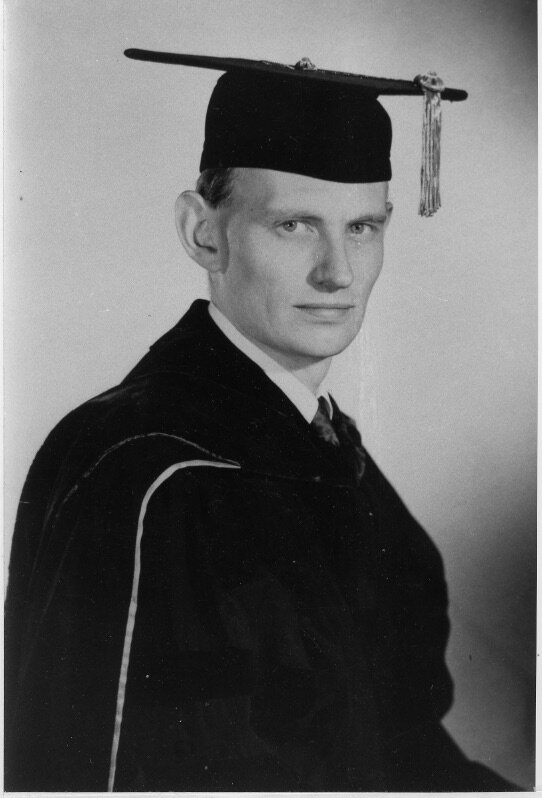

In 1951, Klüver graduated from the Royal Institute of Technology with a degree in electrical engineering. Before coming to the United States to continue his education, he worked at a Paris lab – a branch of Thomson CSF – which had a contract to build an underwater television camera for Jacques Cousteau. Cue Wes Anderson…In Marseilles, Klüver introduced himself to Cousteau as a “willing worker.” As he recalled, the French diver and science popularizer felt Klüver’s arms before inviting him to join the crew of Calypso. He spent that summer helping the crew recover materials from ancient Greek shipwreck off the French Riviera coast.A year later, Klüver was enrolled in the Ph.D. program at Berkeley’s Electrical Engineering Department. The three years it took him to finish his degree was a process Klüver referred to several times as boring and intellectually stifling. Driven by Cold War defense needs, enrollment in programs like Klüver rose dramatically and the focus was much less on the underlying meaning of what, say, quantum mechanics meant. Instead, students were taught to “shut up and calculate.” For Klüver, who had a longstanding interest in philosophy – in Paris he audited courses by Maurice Merleau-Ponty at the Sorbonne – this was frustrating; Klüver later recalled how a physics professors expressing disapproval at his extramural interests. Despite this, Klüver became friends with Dick Foster who helped organize film showing at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art. Like Klüver, Foster had another life outside art and film – he worked at the Stanford Research Institute as a national security analyst. Together, the two of them traveled to Big Sur where they hung out with Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, and Allen Ginsberg.Klüver graduated in 1957 with his Ph.D. in electrical engineering – his specialty was microwave and, later, laser physics, topics made hot by Cold War defense needs. When he finished his degree, Klüver – like many other physicists and engineers in his cohort – had several jobs open to him. RCA, Raytheon, and Stanford Research Institute all courted him with generous offers but Klüver opted to take a job at Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, NJ – arguably the world’s best corporate research lab at the time – as a member of the Technical Staff in Communications Research Department.

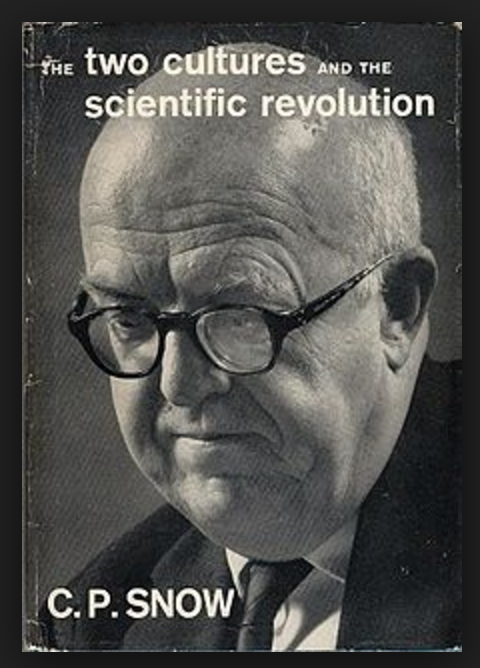

Driven by Cold War defense needs, enrollment in programs like Klüver rose dramatically and the focus was much less on the underlying meaning of what, say, quantum mechanics meant. Instead, students were taught to “shut up and calculate.” For Klüver, who had a longstanding interest in philosophy – in Paris he audited courses by Maurice Merleau-Ponty at the Sorbonne – this was frustrating; Klüver later recalled how a physics professors expressing disapproval at his extramural interests. Despite this, Klüver became friends with Dick Foster who helped organize film showing at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art. Like Klüver, Foster had another life outside art and film – he worked at the Stanford Research Institute as a national security analyst. Together, the two of them traveled to Big Sur where they hung out with Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, and Allen Ginsberg.Klüver graduated in 1957 with his Ph.D. in electrical engineering – his specialty was microwave and, later, laser physics, topics made hot by Cold War defense needs. When he finished his degree, Klüver – like many other physicists and engineers in his cohort – had several jobs open to him. RCA, Raytheon, and Stanford Research Institute all courted him with generous offers but Klüver opted to take a job at Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, NJ – arguably the world’s best corporate research lab at the time – as a member of the Technical Staff in Communications Research Department. At Bell Lab’s, Klüver’s boss was John R. Pierce. It was a good fit. In addition to his legendary acumen as an electrical engineer and research manager – he helped pioneer early satellite communications, among other things – Pierce also wrote sci-fi and had a longstanding interest in both modern art and experimental electronic music. Pierce was generous in tolerating, even indirectly enabling, Klüver’s later art and technology initiatives, a managerial decision made easy by the flush economic circumstances that Bell Labs was in during the 1960s.Soon after he started working at Bell Labs, Klüver encountered C.P. Snow’s famous “Two Cultures” lectures when they were published in 1959 in two installments in the magazine Encounter. Klüver later recalled that he “reacted very strongly against it. I didn’t feel he had the right to divide society into two separate cultures…But perhaps it was his call for action to bridge the gap that I subconsciously agreed with.”

At Bell Lab’s, Klüver’s boss was John R. Pierce. It was a good fit. In addition to his legendary acumen as an electrical engineer and research manager – he helped pioneer early satellite communications, among other things – Pierce also wrote sci-fi and had a longstanding interest in both modern art and experimental electronic music. Pierce was generous in tolerating, even indirectly enabling, Klüver’s later art and technology initiatives, a managerial decision made easy by the flush economic circumstances that Bell Labs was in during the 1960s.Soon after he started working at Bell Labs, Klüver encountered C.P. Snow’s famous “Two Cultures” lectures when they were published in 1959 in two installments in the magazine Encounter. Klüver later recalled that he “reacted very strongly against it. I didn’t feel he had the right to divide society into two separate cultures…But perhaps it was his call for action to bridge the gap that I subconsciously agreed with.” At about the read Snow’s diagnosis, Klüver and his friend Pontus Hultén began making trips around the New York City area – Klüver had a car – to visit artists. In addition to lofts and studios in New York, they ventured forth to Connecticut where they met the Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo and kinetic artist Alexander Calder. By this time, he had also met Swedish artist Jean Tinguely and soon helped him build his infamous “Homage to New York.” On St. Patrick’s Day in 1960, Klüver was in the courtyard at the Museum of Modern Art “Homage” – with its bicycle wheels, piano, a child’s cart, bottles, bathtub, and a “money thrower” contributed by Robert Rauschenberg – stuttered, wheezed, smoked, and staggered its way to self-destruction.

At about the read Snow’s diagnosis, Klüver and his friend Pontus Hultén began making trips around the New York City area – Klüver had a car – to visit artists. In addition to lofts and studios in New York, they ventured forth to Connecticut where they met the Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo and kinetic artist Alexander Calder. By this time, he had also met Swedish artist Jean Tinguely and soon helped him build his infamous “Homage to New York.” On St. Patrick’s Day in 1960, Klüver was in the courtyard at the Museum of Modern Art “Homage” – with its bicycle wheels, piano, a child’s cart, bottles, bathtub, and a “money thrower” contributed by Robert Rauschenberg – stuttered, wheezed, smoked, and staggered its way to self-destruction. Klüver’s view of auto-destructing artwork differed from critics who saw it as an nihilistic expression of about technology. “In the same way as a scientific experiment can never fail, this experiment in art could never fail,” he wrote in 1960. Judging Homage on the basis of whether it worked perfectly – and it certainly didn’t – would be a mistake. Inspired by the possibilities of engineering, the artist had turned engineers for help. “As an engineer, working with him,” Klüver concluded, “I was part of the machine.”By this point, Klüver literally had one foot in each of Snow’s Two Cultures. Part of his time was spent doing physics at Bell Labs in northern New Jersey. The rest of it was spent, a world apart, in Manhattan where he worked with Rauschenberg, Yvonne Rainer, Andy Warhol, and Jasper Johns while attending avant-garde theatre and dance performances and taking part in the burgeoning “Happenings” scene.

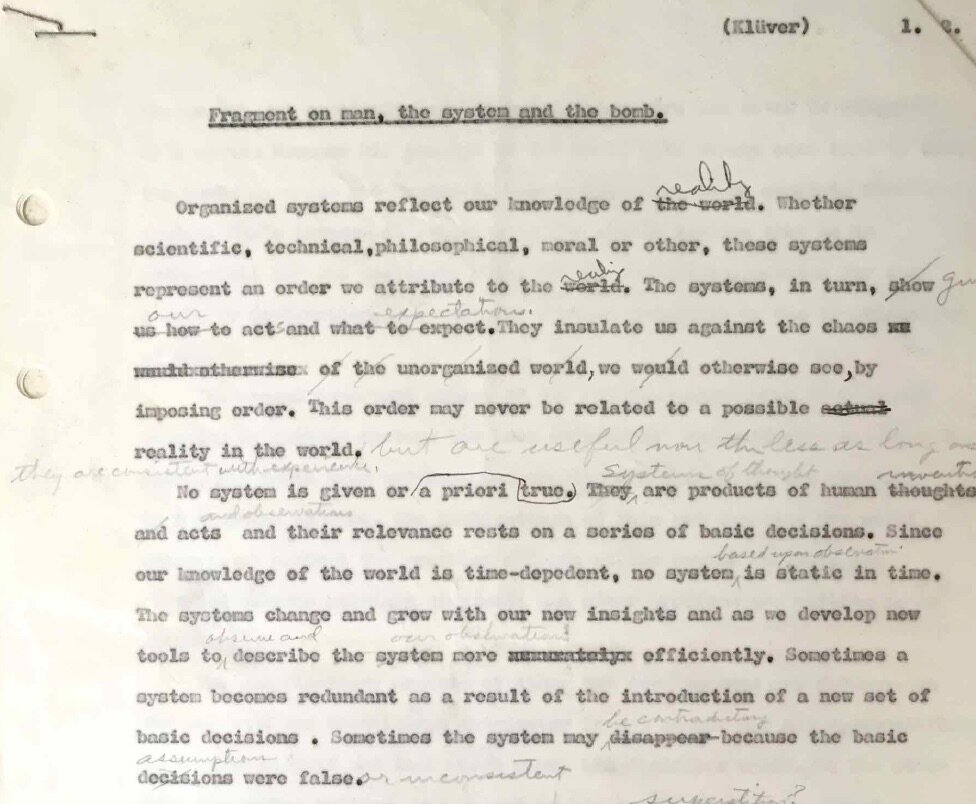

Klüver’s view of auto-destructing artwork differed from critics who saw it as an nihilistic expression of about technology. “In the same way as a scientific experiment can never fail, this experiment in art could never fail,” he wrote in 1960. Judging Homage on the basis of whether it worked perfectly – and it certainly didn’t – would be a mistake. Inspired by the possibilities of engineering, the artist had turned engineers for help. “As an engineer, working with him,” Klüver concluded, “I was part of the machine.”By this point, Klüver literally had one foot in each of Snow’s Two Cultures. Part of his time was spent doing physics at Bell Labs in northern New Jersey. The rest of it was spent, a world apart, in Manhattan where he worked with Rauschenberg, Yvonne Rainer, Andy Warhol, and Jasper Johns while attending avant-garde theatre and dance performances and taking part in the burgeoning “Happenings” scene. Back at Bell Labs, Klüver continued publishing his research in internal Bell papers as well as mainstream engineering journals. His c.v. lists also 10 patents (several are described here) with his name on them from the 1960s. He was also beginning to write short essays about art, technology, and society. It’s through the preservation efforts of Klüver’s widow, Julie Martin, that these are available. They provide a fascinating window into the thoughts of an engineer trying to reconcile his interests and expertise with ideas, trends, and concerns from the humanities and the art world.For example, in 1960, Klüver published a short essay in a short-lived art and literary review called The Hasty Papers that the painter Alfred Leslie published. Called “Fragment on Man and the System,” Klüver described it as a collection of the “jumbled thoughts, my youth, and my many influences.”

Back at Bell Labs, Klüver continued publishing his research in internal Bell papers as well as mainstream engineering journals. His c.v. lists also 10 patents (several are described here) with his name on them from the 1960s. He was also beginning to write short essays about art, technology, and society. It’s through the preservation efforts of Klüver’s widow, Julie Martin, that these are available. They provide a fascinating window into the thoughts of an engineer trying to reconcile his interests and expertise with ideas, trends, and concerns from the humanities and the art world.For example, in 1960, Klüver published a short essay in a short-lived art and literary review called The Hasty Papers that the painter Alfred Leslie published. Called “Fragment on Man and the System,” Klüver described it as a collection of the “jumbled thoughts, my youth, and my many influences.” It later appeared on the same page as a poem by William Carlos Williams and bundled together with contributions from Allen Ginsberg, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Frank O’Hara. Klüver noted that the engineer – the “system builder” – had a new capacity to understand and analyze complex general systems. Yet, “he appears to be unable to make contact with reality.” As a result, these systems – critiques of technology in the 1960s often honed in on The System – were, as a result, “drifting without guidance from meaningful decisions.” There was a gap, Klüver said, between the individual and the system builder which must be closed so that the former becomes an active element of the system.Two features of Klüver’s essay stand out. First, he wrote it in the absence of any established canon of what today we call Science and Technology Studies. The 1960s saw all sorts of increasingly sophisticated critiques about technology – from Lewis Mumford to Jacques Ellul to the environmental movement and student left. The Society for the History of Technology had only just formed in 1958; the Society for the Social Studies of Science didn’t come along until 1975. So, when Klüver wrote his piece – he started drafting it while he was still at Berkeley, he didn’t have access to these critiques which followed. Therefore, I see his essay – general and often vague as it is – as a sort of proto-STS essay.Second, as he later described it, this short essay “contained the seeds” for what became Experiments in Art and Technology, the non-profit he co-founded (with Rauschenberg, artist Robert Whitman, and Bell engineer Fred Waldhauer) in 1966 in the midst of organizing 9 Evenings. Klüver was trying to articulate that technology is not deterministic and that people – “the individual” (artist) – can work with the “system builder” (the engineer) to change it. In the go-go techno-utopian year of 1960, this sort of thinking from an engineer – especially one such as Klüver whose employment was so deeply tied to the Cold War System – was unusually forward-thinking.Following his experiences with Tingueley and Homage, Klüver began to give greater thought to how he might get his Bell Labs colleagues to leap across Snow’s Two Cultures and interface with artists. In September 1962, for example, he circulated a memo around the lab suggesting that Bell Labs start an “Arts and Science Club.” Its purpose would be to “establish direct contact between working artists and Bell Laboratory employees” and acquaint the latter with “the formidable mass of modern art” that was being made just thirty miles away.

It later appeared on the same page as a poem by William Carlos Williams and bundled together with contributions from Allen Ginsberg, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Frank O’Hara. Klüver noted that the engineer – the “system builder” – had a new capacity to understand and analyze complex general systems. Yet, “he appears to be unable to make contact with reality.” As a result, these systems – critiques of technology in the 1960s often honed in on The System – were, as a result, “drifting without guidance from meaningful decisions.” There was a gap, Klüver said, between the individual and the system builder which must be closed so that the former becomes an active element of the system.Two features of Klüver’s essay stand out. First, he wrote it in the absence of any established canon of what today we call Science and Technology Studies. The 1960s saw all sorts of increasingly sophisticated critiques about technology – from Lewis Mumford to Jacques Ellul to the environmental movement and student left. The Society for the History of Technology had only just formed in 1958; the Society for the Social Studies of Science didn’t come along until 1975. So, when Klüver wrote his piece – he started drafting it while he was still at Berkeley, he didn’t have access to these critiques which followed. Therefore, I see his essay – general and often vague as it is – as a sort of proto-STS essay.Second, as he later described it, this short essay “contained the seeds” for what became Experiments in Art and Technology, the non-profit he co-founded (with Rauschenberg, artist Robert Whitman, and Bell engineer Fred Waldhauer) in 1966 in the midst of organizing 9 Evenings. Klüver was trying to articulate that technology is not deterministic and that people – “the individual” (artist) – can work with the “system builder” (the engineer) to change it. In the go-go techno-utopian year of 1960, this sort of thinking from an engineer – especially one such as Klüver whose employment was so deeply tied to the Cold War System – was unusually forward-thinking.Following his experiences with Tingueley and Homage, Klüver began to give greater thought to how he might get his Bell Labs colleagues to leap across Snow’s Two Cultures and interface with artists. In September 1962, for example, he circulated a memo around the lab suggesting that Bell Labs start an “Arts and Science Club.” Its purpose would be to “establish direct contact between working artists and Bell Laboratory employees” and acquaint the latter with “the formidable mass of modern art” that was being made just thirty miles away. Drawing on C.P. Snow, Klüver asked how one could find a better representation – and opportunity – “than in Bell Labs and in the artist’s world in New York.” Artists, he said, were very interested in science and engineering.” And yet, the paradox is that "many technical problems and dreams of the artists” needed input from engineers and scientists. Klüver proposed to broker an arranged marriage between them. “It would not be surprising,” he wrote, “if the scientist could inspire the artist by presenting new problems to him.”Nothing, so far as the historical record is concerns, appears to have come from Klüver’s memo. 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering was still four years away. But the seeds for what became that event – the intellectual and organizational momentum needed to realize it – was already taking shape and form in Klüver’s mind. “Technology needs an examiner, a stimulator, a teaser, a stripper. The artist’s use of technology gives us this goal,” he wrote in a Swedish magazine in 1966, “What is left for the engineer is to see to it that the artist is not too late.”Note: This is the second in a series of blog posts about 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, a multi-media event that helped launch the 1960s-era art and technology movement and now offers a touchstone for New Media Art and analysis. The first installment is here...

Drawing on C.P. Snow, Klüver asked how one could find a better representation – and opportunity – “than in Bell Labs and in the artist’s world in New York.” Artists, he said, were very interested in science and engineering.” And yet, the paradox is that "many technical problems and dreams of the artists” needed input from engineers and scientists. Klüver proposed to broker an arranged marriage between them. “It would not be surprising,” he wrote, “if the scientist could inspire the artist by presenting new problems to him.”Nothing, so far as the historical record is concerns, appears to have come from Klüver’s memo. 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering was still four years away. But the seeds for what became that event – the intellectual and organizational momentum needed to realize it – was already taking shape and form in Klüver’s mind. “Technology needs an examiner, a stimulator, a teaser, a stripper. The artist’s use of technology gives us this goal,” he wrote in a Swedish magazine in 1966, “What is left for the engineer is to see to it that the artist is not too late.”Note: This is the second in a series of blog posts about 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, a multi-media event that helped launch the 1960s-era art and technology movement and now offers a touchstone for New Media Art and analysis. The first installment is here...