50 Years of Art & Engineering

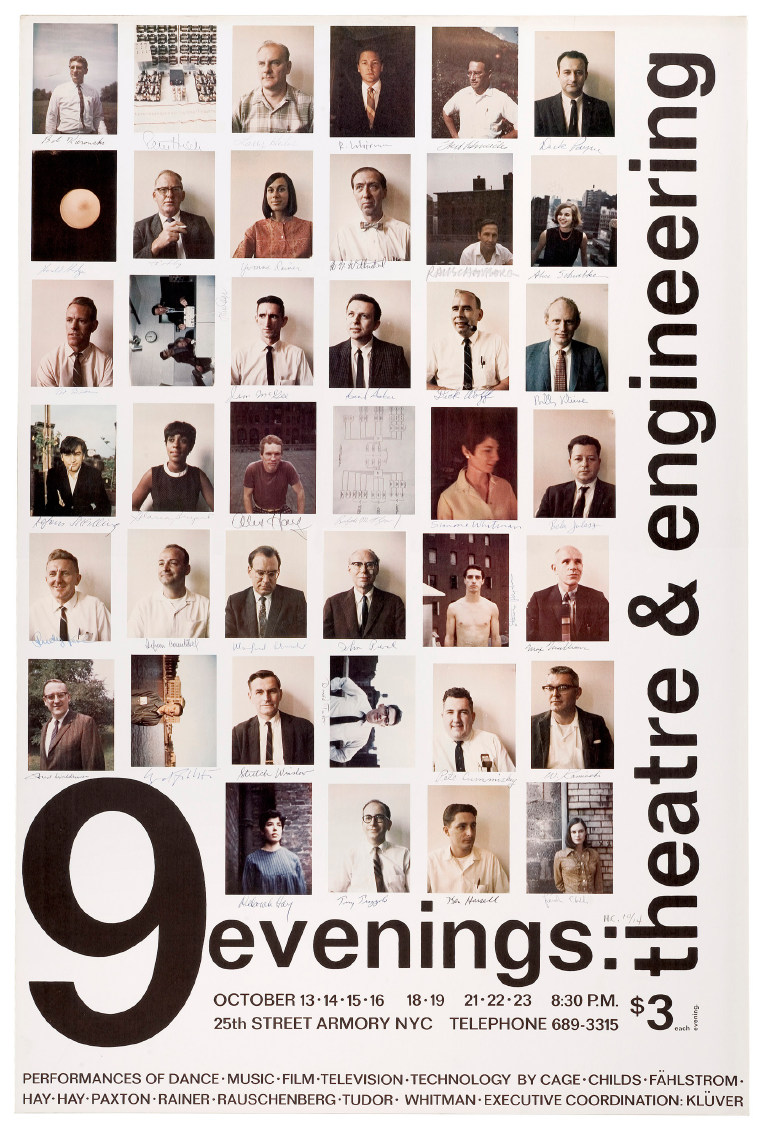

50 years ago, accomplished professionals from two supposedly very different communities – high-tech research and avant-garde art – came together and fused at the 69th Regiment Armory building in New York City. More than three dozen engineers from nearby Bell Laboratories, arguably the world’s preeminent corporate research laboratory, joined with artists like Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, and Lucinda Childs to create ten distinct multi-media pieces for 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering. In October 1966, thousands of art enthusiasts, critics, and curiosity seekers trekked to midtown Manhattan to see and, in some cases, participate in performances that blended dance, music, and the visual arts with sophisticated electrical and communications engineering. This fall marks the half-century mark of 9 Evenings. Because I’m writing a new book (called Art ReWired) about the intersection of engineers and artists, I thought a series of short blog posts about the seminal event would be both timely and brain-stimulating.

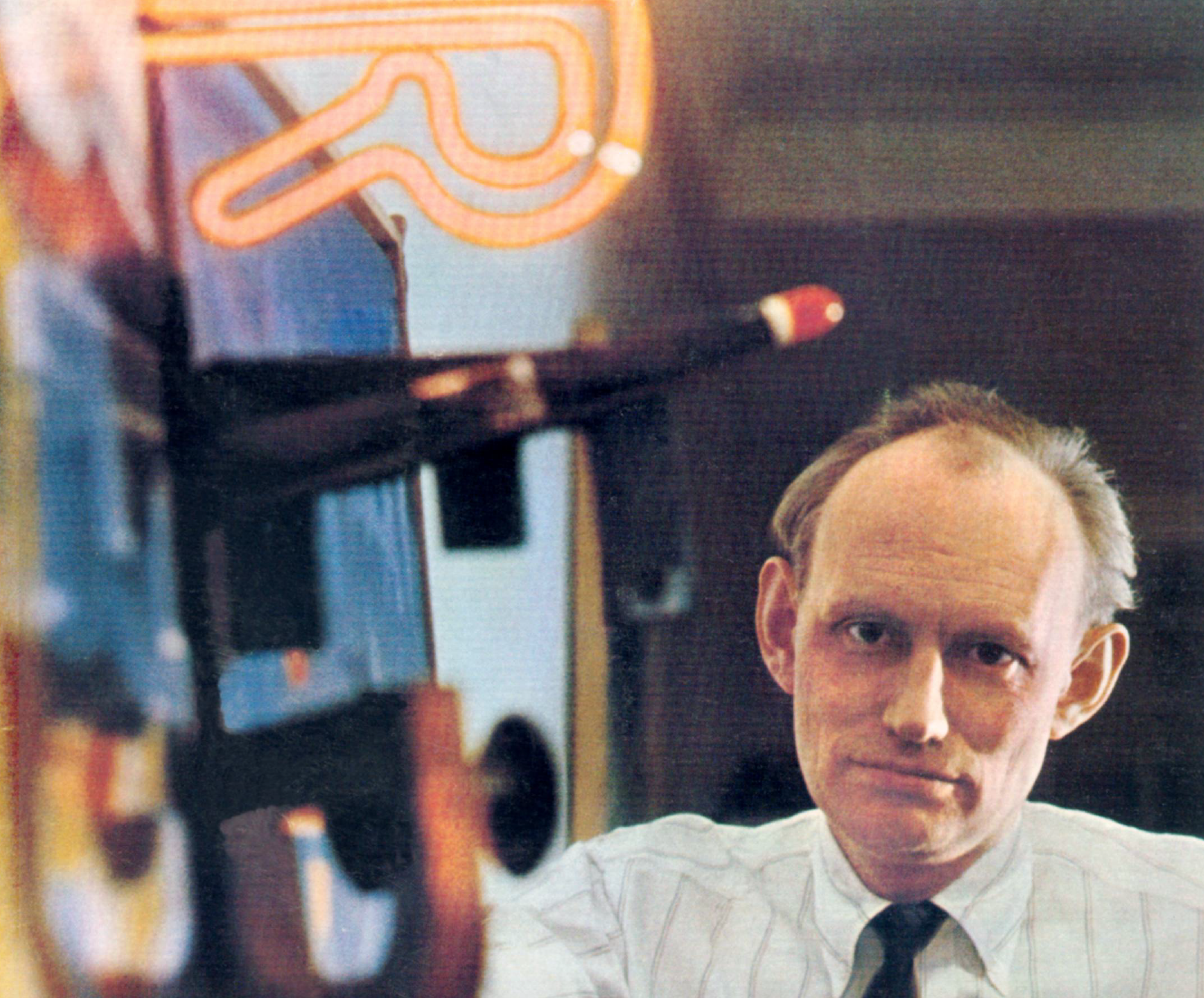

This fall marks the half-century mark of 9 Evenings. Because I’m writing a new book (called Art ReWired) about the intersection of engineers and artists, I thought a series of short blog posts about the seminal event would be both timely and brain-stimulating. The backstory to 9 Evenings is complex but the central figure in it is Wilhelm “Billy” Klüver (1927-2004). Long interested in experimental film and modern art, in the early 1960s the Swedish-born and Berkeley-trained engineer worked at Bell Labs. He also spent evenings and weekends assisting with artists like Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol and helping organize major art shows. The symbolism of having 9 Evenings at the Armory was obvious. In 1913, it had hosted a famous and controversial exhibition which helped to publicly present modern art to American viewers.

The backstory to 9 Evenings is complex but the central figure in it is Wilhelm “Billy” Klüver (1927-2004). Long interested in experimental film and modern art, in the early 1960s the Swedish-born and Berkeley-trained engineer worked at Bell Labs. He also spent evenings and weekends assisting with artists like Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol and helping organize major art shows. The symbolism of having 9 Evenings at the Armory was obvious. In 1913, it had hosted a famous and controversial exhibition which helped to publicly present modern art to American viewers. In 1966, as 9 Evenings was coming together, Klüver also helped establish the New York-based group Experiments in Art and Technology. E.A.T., as it was better known, brought artists and engineers together, generating what were sociological, as well as artistic and technological experiments. From one-on-one collaborations to large-scale ambitions that mirrored Cold War-era Big Science projects, E.AT. was highly visible, sometimes successful, and always controversial.

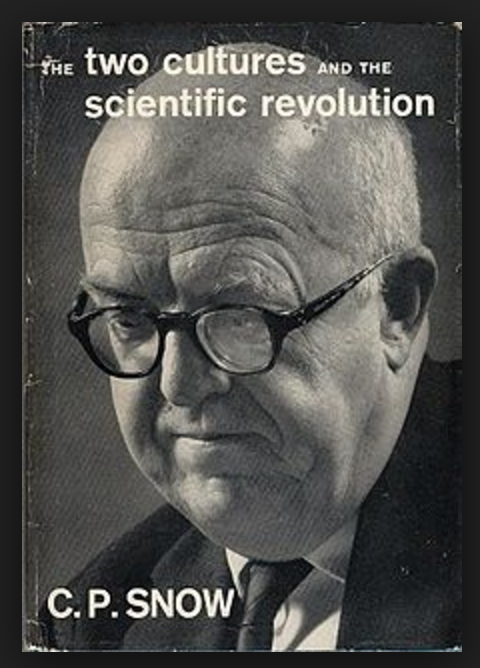

In 1966, as 9 Evenings was coming together, Klüver also helped establish the New York-based group Experiments in Art and Technology. E.A.T., as it was better known, brought artists and engineers together, generating what were sociological, as well as artistic and technological experiments. From one-on-one collaborations to large-scale ambitions that mirrored Cold War-era Big Science projects, E.AT. was highly visible, sometimes successful, and always controversial. 9 Evenings stands out as the most visible opening salvo in what became the “art and technology” movement of the long 1960s. Bracketed by the launch of Sputnik on one end and the Watergate scandal at the other, the movement unfolded in the U.S. and Europe and was marked by scores of collaborations between artists and engineers. Sometimes these collaborations were between curious individuals; in other cases, they involved scores of people and multi-millions dollar budgets. For artists, it was partly a desire to work with new technology and a sense of crisis about the relevance of object-oriented art. For engineers, working with artists was an opportunity to bridge C.P. Snow’s famous “Two Cultures” divide and show technology and engineering as a positive force in society.

9 Evenings stands out as the most visible opening salvo in what became the “art and technology” movement of the long 1960s. Bracketed by the launch of Sputnik on one end and the Watergate scandal at the other, the movement unfolded in the U.S. and Europe and was marked by scores of collaborations between artists and engineers. Sometimes these collaborations were between curious individuals; in other cases, they involved scores of people and multi-millions dollar budgets. For artists, it was partly a desire to work with new technology and a sense of crisis about the relevance of object-oriented art. For engineers, working with artists was an opportunity to bridge C.P. Snow’s famous “Two Cultures” divide and show technology and engineering as a positive force in society. Today, 9 Evenings appears as a model for how art and technology could combine into a new creative force. It’s nearly impossible to visit a display of contemporary art without seeing at least one piece deploying some digital or video technology. Meanwhile, artists like Eduardo Kac have blended bioengineering and art in ways that dissolve any boundaries between them.The roots of this hybridization, of course, can be traced to many sources but a primary one is 9 Evenings. Science historian Arthur I. Miller opened his recent intriguing (but ultimately flawed) book Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-Edge Science is Re-Defining Contemporary Art with a vignette drawn from 9 Evenings. More recently, Michelle Kuo, editor of Artforum, suggested that lessons from 9 Evenings seeped into and informed Silicon Valley’s culture of technological disruption. In addition to providing ample material for several doctoral dissertations, Seattle will see the commemoration of the “artistic traditions” 9 Evenings introduced and celebrate the power of collaboration and creativity via a multi-day art, technology, and science festival called 9E2.The enthusiasm and interest shown by digital and New Media Art scholars – a diverse and multi-disciplinary community to be sure – in 9 Evenings as a critical origin point for their topic of study is ironic given its silent treatment in art history. If one picks up any recent survey of modern art, the art and technology movement, let alone 9 Evenings, isn’t likely to appear. One would be hard pressed to even find “technology” in the index of such books.

Today, 9 Evenings appears as a model for how art and technology could combine into a new creative force. It’s nearly impossible to visit a display of contemporary art without seeing at least one piece deploying some digital or video technology. Meanwhile, artists like Eduardo Kac have blended bioengineering and art in ways that dissolve any boundaries between them.The roots of this hybridization, of course, can be traced to many sources but a primary one is 9 Evenings. Science historian Arthur I. Miller opened his recent intriguing (but ultimately flawed) book Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-Edge Science is Re-Defining Contemporary Art with a vignette drawn from 9 Evenings. More recently, Michelle Kuo, editor of Artforum, suggested that lessons from 9 Evenings seeped into and informed Silicon Valley’s culture of technological disruption. In addition to providing ample material for several doctoral dissertations, Seattle will see the commemoration of the “artistic traditions” 9 Evenings introduced and celebrate the power of collaboration and creativity via a multi-day art, technology, and science festival called 9E2.The enthusiasm and interest shown by digital and New Media Art scholars – a diverse and multi-disciplinary community to be sure – in 9 Evenings as a critical origin point for their topic of study is ironic given its silent treatment in art history. If one picks up any recent survey of modern art, the art and technology movement, let alone 9 Evenings, isn’t likely to appear. One would be hard pressed to even find “technology” in the index of such books. This presents a puzzle. Many of the artists – Rauschenberg, Warhol, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg as well as a host of lesser-known figures – who populate the art history canon were dabblers if not eager participants in the larger art and technology movement. Their experimentation with technology and collaboration with engineers is camouflaged in favor of their more familiar accomplishments. We might see discussion of Rauschenberg’s “combines”, for instance, but his years-long collaborations with Klüver or his participation in E.A.T. are absent.

This presents a puzzle. Many of the artists – Rauschenberg, Warhol, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg as well as a host of lesser-known figures – who populate the art history canon were dabblers if not eager participants in the larger art and technology movement. Their experimentation with technology and collaboration with engineers is camouflaged in favor of their more familiar accomplishments. We might see discussion of Rauschenberg’s “combines”, for instance, but his years-long collaborations with Klüver or his participation in E.A.T. are absent. Perhaps this isn’t so shocking when one considers that art, broadly speaking, is itself largely absent from histories of modern science and technology. Piling on more irony – both art history and the histories of science and technology are themselves small islets comprising the larger archipelago of mainstream history. They have their own departments, journals, professional societies, meetings and so on. One is unlikely to see much art or science or technology appear in mainstream journals like American Historical Review.While finding a better seat at History's Big Table for art or technology might is a long-term and probably unrealistic project, it’s not unreasonable to look for ways in which of Clio’s semi-orphans can better engage with one another. People who look at the histories of art and science/technology share some common interests. A few that jump to mind include: how experiments are created and executed; patronage and the situation of art (or engineering) within a large political economy; the pursuit and effects of publicity and publishing; and questions about creativity and moral responsibility. Moreover, we can interpret productions like 9 Evenings as an art world version of 1960s-era Big Science. Whether it was Big Science or Big Art c. 1966, Cold War engineers were central actors in both.Despite its overuse, C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” diagnosis – despite decades of hand-wringing and curriculum re-jiggering by academic administrators – has never disappeared or been dispatched. Its echoes appear in today’s calls to introduce an “A for Art” into STEM education (Hey! You get STEAM!)

Perhaps this isn’t so shocking when one considers that art, broadly speaking, is itself largely absent from histories of modern science and technology. Piling on more irony – both art history and the histories of science and technology are themselves small islets comprising the larger archipelago of mainstream history. They have their own departments, journals, professional societies, meetings and so on. One is unlikely to see much art or science or technology appear in mainstream journals like American Historical Review.While finding a better seat at History's Big Table for art or technology might is a long-term and probably unrealistic project, it’s not unreasonable to look for ways in which of Clio’s semi-orphans can better engage with one another. People who look at the histories of art and science/technology share some common interests. A few that jump to mind include: how experiments are created and executed; patronage and the situation of art (or engineering) within a large political economy; the pursuit and effects of publicity and publishing; and questions about creativity and moral responsibility. Moreover, we can interpret productions like 9 Evenings as an art world version of 1960s-era Big Science. Whether it was Big Science or Big Art c. 1966, Cold War engineers were central actors in both.Despite its overuse, C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” diagnosis – despite decades of hand-wringing and curriculum re-jiggering by academic administrators – has never disappeared or been dispatched. Its echoes appear in today’s calls to introduce an “A for Art” into STEM education (Hey! You get STEAM!) In the next few blog posts, I’m going to look more closely at 9 Evenings. Fascinating in its own right as the earliest, biggest, and brightest art & tech collaboration from the long 1960s, a half-century later it offers a case study for how art and technology (and their histories) might talk to one another.

In the next few blog posts, I’m going to look more closely at 9 Evenings. Fascinating in its own right as the earliest, biggest, and brightest art & tech collaboration from the long 1960s, a half-century later it offers a case study for how art and technology (and their histories) might talk to one another.

Next Time: Billy Klüver – the Engineer as Artwork