From Laser Art to Laserium

The folks at Science Friday included me today in a story about the ways in which the laser migrated from scientists' labs to art galleries and planetariums. If you liked the show, here's more of the story...This advertisement, published just a few years after the first optical lasers were demonstrated, asked the question: “Where does the laser go from here?” One of the places it went was the artist’s studio and the art gallery. For example, In Washington, DC, artist Rockne Krebs started experimenting in 1967 with lasers and produced several innovative installations.

One of the places it went was the artist’s studio and the art gallery. For example, In Washington, DC, artist Rockne Krebs started experimenting in 1967 with lasers and produced several innovative installations. Another part of this story was the career of physicist Elsa Garmire. Trained at Harvard and then MIT in the 1960s, Garmire was a pioneer in laser research.

Another part of this story was the career of physicist Elsa Garmire. Trained at Harvard and then MIT in the 1960s, Garmire was a pioneer in laser research. In the late 1960s, while doing a postdoc at Caltech, Garmire began to experiment with using lasers to make art. Initially, she created “lasergrams” – photographs made by shining laser beams through various diffraction media. Here’s one example from 1969.

In the late 1960s, while doing a postdoc at Caltech, Garmire began to experiment with using lasers to make art. Initially, she created “lasergrams” – photographs made by shining laser beams through various diffraction media. Here’s one example from 1969. Garmire also explored a variation on photographing manipulated laser images via live shows using a HeNe laser and rotating diffraction wheels and then filming the changing shapes and colors. This sowed the seeds for what eventually became Laserium.

Garmire also explored a variation on photographing manipulated laser images via live shows using a HeNe laser and rotating diffraction wheels and then filming the changing shapes and colors. This sowed the seeds for what eventually became Laserium. Before she returned to a very successful full-time career in scientific research, Garmire’s experimental live laser shows caught the attention of Ivan Dryer, a Los Angeles-based film maker.

Before she returned to a very successful full-time career in scientific research, Garmire’s experimental live laser shows caught the attention of Ivan Dryer, a Los Angeles-based film maker. Dryer soon realized that filming Garmire’s laser images was aesthetically inferior to seeing the intensity and purity of their colors in person. In the fall of 1970, he arranged for a live and – to his eyes – captivating demonstration of Garmire’s system, accompanied by classical music, for staff at the Griffith Observatory. The observatory management, however, was less enchanted with what they saw as entertainment, not education. Disappointed but still motivated, Dryer and Garmire co-founded a company in February 1971 called Laser Images Inc.. Riffing on the popularity of planetarium shows, they called their product “Laserium.”

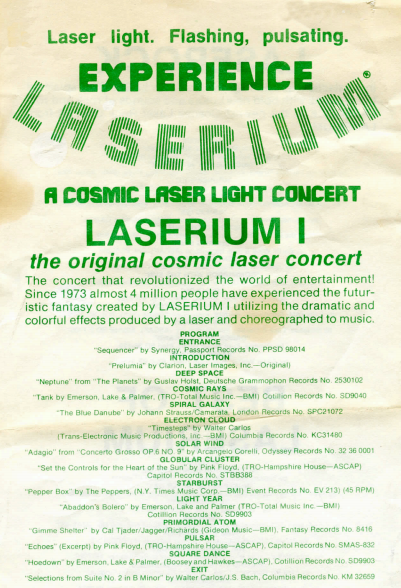

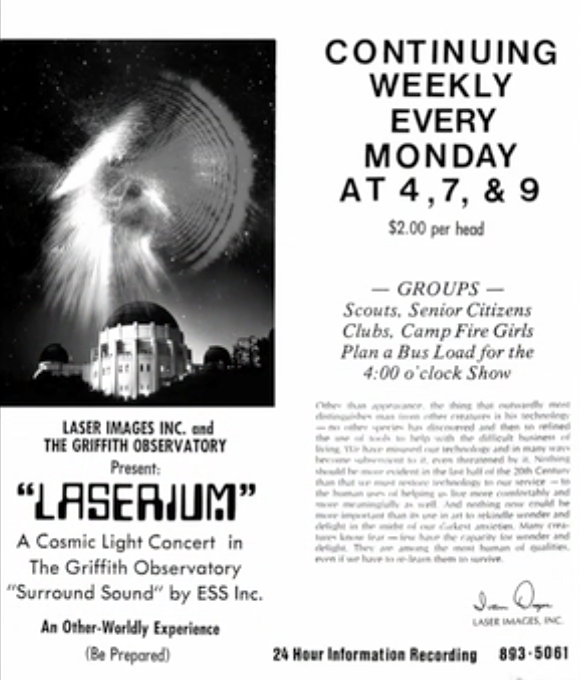

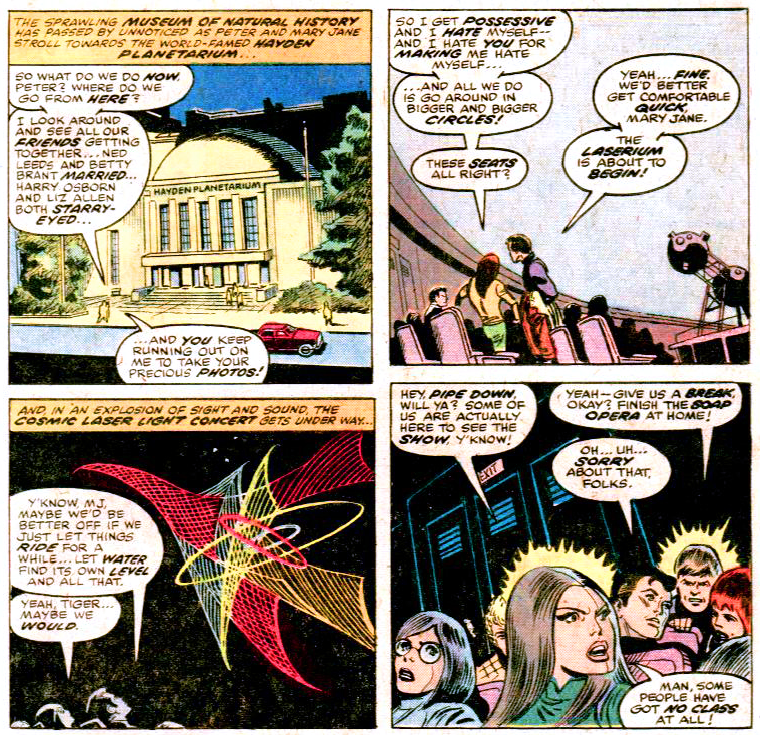

Dryer soon realized that filming Garmire’s laser images was aesthetically inferior to seeing the intensity and purity of their colors in person. In the fall of 1970, he arranged for a live and – to his eyes – captivating demonstration of Garmire’s system, accompanied by classical music, for staff at the Griffith Observatory. The observatory management, however, was less enchanted with what they saw as entertainment, not education. Disappointed but still motivated, Dryer and Garmire co-founded a company in February 1971 called Laser Images Inc.. Riffing on the popularity of planetarium shows, they called their product “Laserium.” The idea eventually took off. Laserium finally debuted at Griffith Observatory in November 1973, running on four consecutive Mondays, three times a day. Advertisements said "Be Prepared." Despite later stereotypes of Laserium, the first shows had no music by Pink Floyd. The run was a success and shows at Griffith continued for 28 years.

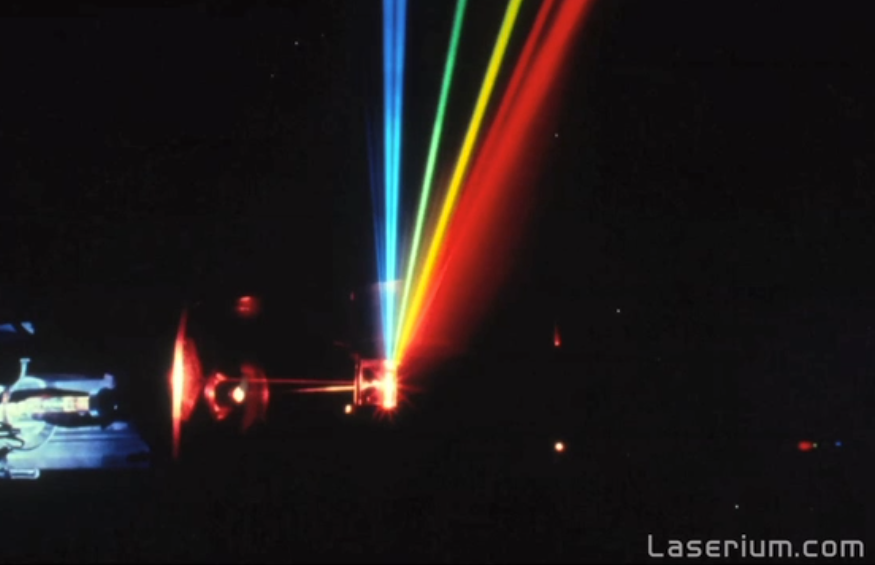

The idea eventually took off. Laserium finally debuted at Griffith Observatory in November 1973, running on four consecutive Mondays, three times a day. Advertisements said "Be Prepared." Despite later stereotypes of Laserium, the first shows had no music by Pink Floyd. The run was a success and shows at Griffith continued for 28 years. By 1977, Dryer’s growing team of live laser performers were putting on shows in more than 15 cities in the U.S. and abroad and Laserium was a registered trademark. Laserium was based around a standard system, using a low power krypton laser split by a prism into four colored beams.

By 1977, Dryer’s growing team of live laser performers were putting on shows in more than 15 cities in the U.S. and abroad and Laserium was a registered trademark. Laserium was based around a standard system, using a low power krypton laser split by a prism into four colored beams. The details of the system are preserved in the patent application Dryer and two colleagues filed in July 1975 for a “laser light image generator” that can create a “plurality of light images in different colors from a single laser light.”

The details of the system are preserved in the patent application Dryer and two colleagues filed in July 1975 for a “laser light image generator” that can create a “plurality of light images in different colors from a single laser light.” Laserium had a broad appeal – stoners, geeks, and planetarium junkies all turned out to see shows. Its popularity was no doubt enhanced by the relative novelty of lasers for the general public in the mid-1970s. The 1977 film Star Wars added to people’s interest in all things laser-y.

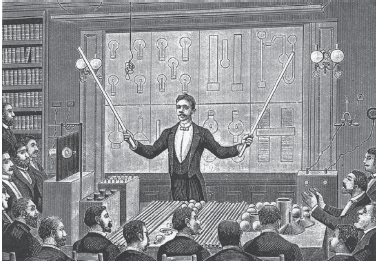

Laserium had a broad appeal – stoners, geeks, and planetarium junkies all turned out to see shows. Its popularity was no doubt enhanced by the relative novelty of lasers for the general public in the mid-1970s. The 1977 film Star Wars added to people’s interest in all things laser-y. Just as planetarium shows have helped popularize astronomy, Laserium can be seen as a public display of laser technology, its roots traceable back to 19th century displays of electricity and electrical effects by people like Michael Faraday and Nikola Tesla.

Just as planetarium shows have helped popularize astronomy, Laserium can be seen as a public display of laser technology, its roots traceable back to 19th century displays of electricity and electrical effects by people like Michael Faraday and Nikola Tesla. Laserium was not without its aesthetic admirers. One art writer, for example, referred to experiments with laser projection as the “seeds of what will become the high, universally acclaimed visual art of the future.” Given Laserium’s penchant for attracting attendees whose appreciation of choreographed laser light was chemically enhanced, “high” visual art takes on another meaning as well.

Laserium was not without its aesthetic admirers. One art writer, for example, referred to experiments with laser projection as the “seeds of what will become the high, universally acclaimed visual art of the future.” Given Laserium’s penchant for attracting attendees whose appreciation of choreographed laser light was chemically enhanced, “high” visual art takes on another meaning as well. After peaking in the late 1970s when some 70 people worked for the company, Laserium slowly faded in popularity. Often lampooned as the preferred entertainment of pot heads and LSD trippers, we can also see Laserium as the somewhat disreputable cousin of the venerable planetarium show. Nonetheless, by 2002, more than 20 million people around the world had seen a Laserium show – its run at Griffith lasted some 28 years – and its idiosyncratic blend of music and spectacle had become part of popular culture.Laserium's story tells us that we can no longer think of the late 1960s and early 1970s as an “anti-science” or “anti-technology” period. A more nuanced reading shows that engineers, artists, and the general public in general sought and found alternative forms of science and technology. Laserium was a colorful off-shoot of this search for a different, groovier, science.

After peaking in the late 1970s when some 70 people worked for the company, Laserium slowly faded in popularity. Often lampooned as the preferred entertainment of pot heads and LSD trippers, we can also see Laserium as the somewhat disreputable cousin of the venerable planetarium show. Nonetheless, by 2002, more than 20 million people around the world had seen a Laserium show – its run at Griffith lasted some 28 years – and its idiosyncratic blend of music and spectacle had become part of popular culture.Laserium's story tells us that we can no longer think of the late 1960s and early 1970s as an “anti-science” or “anti-technology” period. A more nuanced reading shows that engineers, artists, and the general public in general sought and found alternative forms of science and technology. Laserium was a colorful off-shoot of this search for a different, groovier, science.