Rockets, Art, & Other Roads Taken

One of the most read - and misread - poems of the 20th century is Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken." Pervasive in high school English courses, titles of self-help books, and even car advertisements, Frost's poem may have been a celebration of individualism. Or, if read more cruelly, it is a reflection on self-deception used to rationalize one's life choices.Engineer Frank J. Malina certainly knew of Frost's poem. Indeed, in the spring of 1953, Malina - then just forty years old - may have been experiencing the hesitation tempered with anticipation that Frost's stanzas expressed. For the third time in his life, Malina found himself at a critical crossroads in his professional career.In 1936, while a graduate student working with the famed Hungarian engineer Theodore von Kármán at Caltech, Malina abandoned a conventional research topic to pursue rocketry. During the Great Depression, especially, this was a risky career choice. The risks were real in other ways. People called Malina's team of rocket builders the "suicide squad" for a reason. Malina's gamble paid off. During World War Two, Caltech's rocket group developed and built thousands of rocket motors for assisting airplane take-offs. Before peace broke out, Malina co-founded the Jet Propulsion Laboratory as well as a company, Aerojet, which became wildly successful during the Cold War. And the WAC Corporal, a sounding rocket Malina imagined and designed, flew to over 240,000 feet in October 1945.

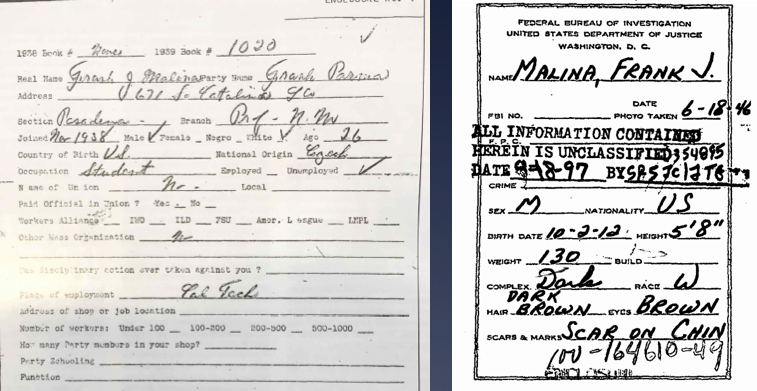

Malina's gamble paid off. During World War Two, Caltech's rocket group developed and built thousands of rocket motors for assisting airplane take-offs. Before peace broke out, Malina co-founded the Jet Propulsion Laboratory as well as a company, Aerojet, which became wildly successful during the Cold War. And the WAC Corporal, a sounding rocket Malina imagined and designed, flew to over 240,000 feet in October 1945. Malina's conscience and the destruction he saw during tours of Europe brought him to a second crossroads. Despite his accomplishments in rocketry - certainly on par with those of the soon-to-be-more-famous Wernher von Braun - and considerable military interest in his work, deepening ideological tensions of the Nuclear Age distressed Malina. In 1947, he left Caltech, moved to Paris, and took a position with the newly formed United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).However, the United States government, and many of its citizens, viewed UNESCO with suspicion. A 1948 article in the Saturday Evening Post, for example, mocked the organization's altruistic goals and made not-so-subtle digs at the left-leaning inclinations of employees like Malina. The FBI had been surveilling the American rocketeer since 1942 and Malina, while a graduate student at Caltech, had openly criticized capitalist economic systems. More likely than not, in fact, Malina was a member of the Communist Party before World War Two started.

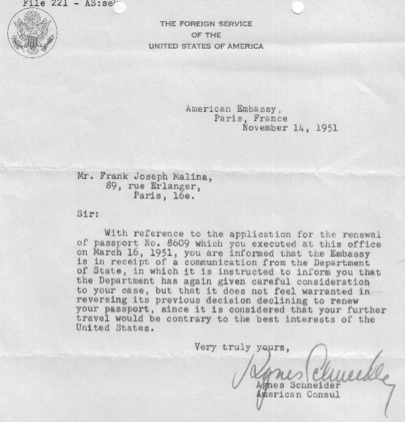

Malina's conscience and the destruction he saw during tours of Europe brought him to a second crossroads. Despite his accomplishments in rocketry - certainly on par with those of the soon-to-be-more-famous Wernher von Braun - and considerable military interest in his work, deepening ideological tensions of the Nuclear Age distressed Malina. In 1947, he left Caltech, moved to Paris, and took a position with the newly formed United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).However, the United States government, and many of its citizens, viewed UNESCO with suspicion. A 1948 article in the Saturday Evening Post, for example, mocked the organization's altruistic goals and made not-so-subtle digs at the left-leaning inclinations of employees like Malina. The FBI had been surveilling the American rocketeer since 1942 and Malina, while a graduate student at Caltech, had openly criticized capitalist economic systems. More likely than not, in fact, Malina was a member of the Communist Party before World War Two started. Any lingering FBI suspicions were confirmed the following year when physicist Frank Oppenheimer and his wife Jackie testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee about Communist activities around Caltech. According to one Washington paper, at the HUAC hearing “the name of Frank J. Malina” was "thrown at them [the Oppenheimers] again and again” by investigators. FBI scrutiny intensified and, when Malina’s passport expired in 1951, the State Department refused to renew it, stating that his travels would harm American interests.

Any lingering FBI suspicions were confirmed the following year when physicist Frank Oppenheimer and his wife Jackie testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee about Communist activities around Caltech. According to one Washington paper, at the HUAC hearing “the name of Frank J. Malina” was "thrown at them [the Oppenheimers] again and again” by investigators. FBI scrutiny intensified and, when Malina’s passport expired in 1951, the State Department refused to renew it, stating that his travels would harm American interests. The FBI issued a warrant for Malina's arrest and explored the possibility of extraditing him from France. At the same time, American pressure on UNESCO curtailed the scope of his travel and research activities. In February 1953, Malina resigned from UNESCO. ((James L. Johnson has written an excellent 2012 article on Malina's travails with the FBI.)) At just about the same time. the value of his Aerojet stock began increasing in value and he decided not to sell it.Malina, now a middle-aged expatriate living in Paris with his second wife and two young sons, was at his third crossroads. Instead of clutching to the familiar - more scientific research, maybe a professorship somewhere in aeronautics - Malina veered to a very different path. He became a professional artist.Malina's choice was not as rash as it might seem. He had long been interested in art, both the making of it as well as pondering the similarities and differences art shared with science. As a graduate student, he made professional-quality engineering drawings for von Kármán. Malina also kept a "Book of Life" where, among other things, he kept track of what he read. It's a wonderful resource that lists many art history books.

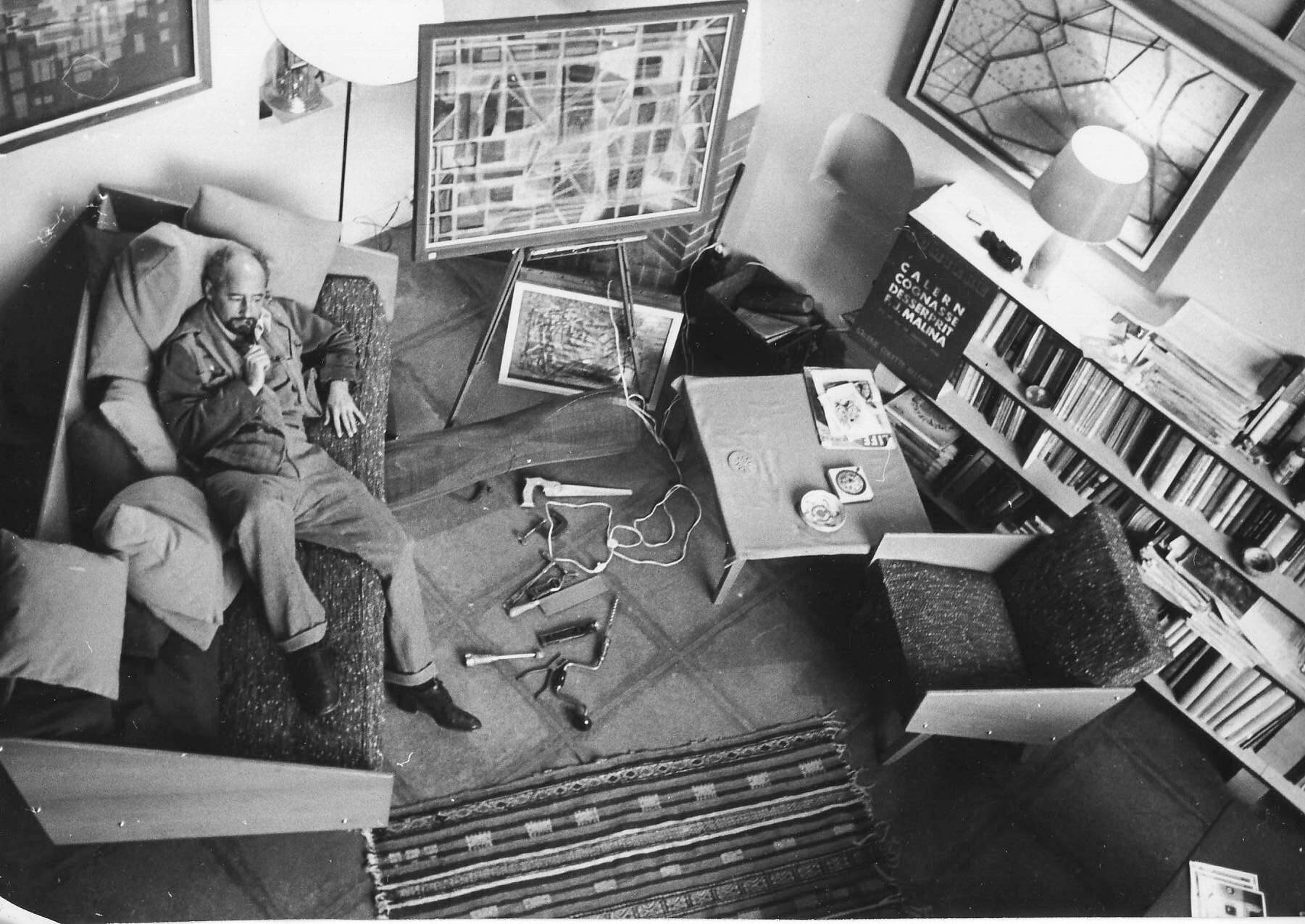

The FBI issued a warrant for Malina's arrest and explored the possibility of extraditing him from France. At the same time, American pressure on UNESCO curtailed the scope of his travel and research activities. In February 1953, Malina resigned from UNESCO. ((James L. Johnson has written an excellent 2012 article on Malina's travails with the FBI.)) At just about the same time. the value of his Aerojet stock began increasing in value and he decided not to sell it.Malina, now a middle-aged expatriate living in Paris with his second wife and two young sons, was at his third crossroads. Instead of clutching to the familiar - more scientific research, maybe a professorship somewhere in aeronautics - Malina veered to a very different path. He became a professional artist.Malina's choice was not as rash as it might seem. He had long been interested in art, both the making of it as well as pondering the similarities and differences art shared with science. As a graduate student, he made professional-quality engineering drawings for von Kármán. Malina also kept a "Book of Life" where, among other things, he kept track of what he read. It's a wonderful resource that lists many art history books. Moreover, Frank's first wife, Lilian, was an artist who, in the late 1930s, did works in a "social realist" fashion before trading California for New York and new artistic styles.

Moreover, Frank's first wife, Lilian, was an artist who, in the late 1930s, did works in a "social realist" fashion before trading California for New York and new artistic styles. Around the time Malina married Lilian, he wrote a short statement setting out his opinions about art and science. In it, one finds seeds of the ideas that Malina later expressed in the pages of Leonardo, the international art-science journal he founded in 1968. Art, Malina opined, was “entirely separate from science.” Science deals with things by test and observation where art does the same but via feeling and emotion. Not solely a product of the intellect, art's function was to create “emotion or mood in its object," serving as an expression of the artist’s emotions and values.

Around the time Malina married Lilian, he wrote a short statement setting out his opinions about art and science. In it, one finds seeds of the ideas that Malina later expressed in the pages of Leonardo, the international art-science journal he founded in 1968. Art, Malina opined, was “entirely separate from science.” Science deals with things by test and observation where art does the same but via feeling and emotion. Not solely a product of the intellect, art's function was to create “emotion or mood in its object," serving as an expression of the artist’s emotions and values. In 1953, after deciding to explore the path of the professional artist, Malina quickly became skeptical of the Parisian art world which, to his mind seemed set up to promote certain styles and artists. He also found himself soon saturated by the plentiful “nudes, flowers, landscapes, and dead fish” on the walls of French galleries and museums. Instead, he turned to subjects he knew well – shock waves, fluid flow, and rocket motors - along with scientific phenomena, particularly those drawn from physics or astronomy, for inspiration.

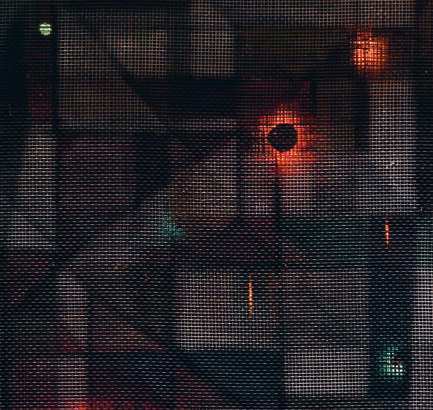

In 1953, after deciding to explore the path of the professional artist, Malina quickly became skeptical of the Parisian art world which, to his mind seemed set up to promote certain styles and artists. He also found himself soon saturated by the plentiful “nudes, flowers, landscapes, and dead fish” on the walls of French galleries and museums. Instead, he turned to subjects he knew well – shock waves, fluid flow, and rocket motors - along with scientific phenomena, particularly those drawn from physics or astronomy, for inspiration. After he was established as a professional artist, Malina imagined how art could serve as a probe of sorts. It could, he wrote in 1966, provide material for psychologists who wanted to understand how and what people saw. The result might be a better theory of aesthetics which could, in turn, make the arts “richer and much more effective.” For many years, he retained this curiosity as to why people saw what they did.This interest manifested itself in one of Malina's early art experiments. These were works made using the moiré effect. For instance, when there are two superimposed wire grids, one may sense visual patterns or even movement as the eye passes over them.

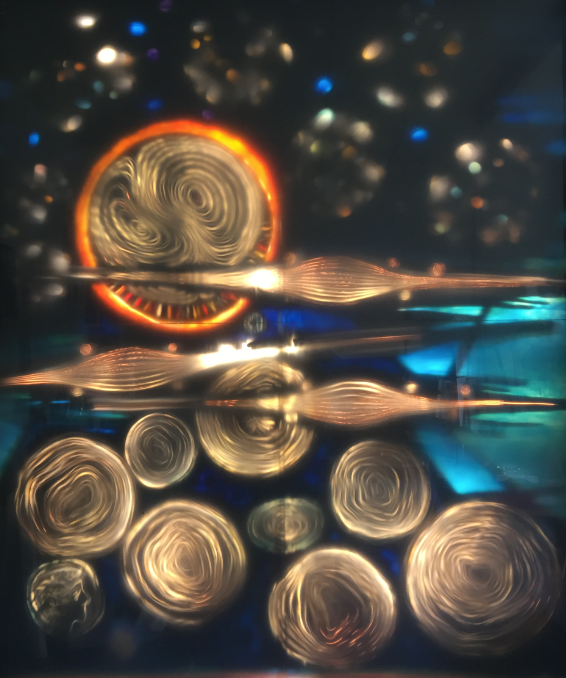

After he was established as a professional artist, Malina imagined how art could serve as a probe of sorts. It could, he wrote in 1966, provide material for psychologists who wanted to understand how and what people saw. The result might be a better theory of aesthetics which could, in turn, make the arts “richer and much more effective.” For many years, he retained this curiosity as to why people saw what they did.This interest manifested itself in one of Malina's early art experiments. These were works made using the moiré effect. For instance, when there are two superimposed wire grids, one may sense visual patterns or even movement as the eye passes over them. Malina wanted increased contrast between the moiré patterns made via wire mesh and their backgrounds. Getting frustrated, he tried back-lighting his works. The effect gave him a "feeling of ecstasy that one experiences” when "making a discovery.” This led to a series of experiments with low wattage bulbs behind compositions of superimposed painted wire mesh. Malina began to call his new works “electro-paintings.”In the months that followed, Malina increased his pace of experimentation. He started a new series of electro-paintings, using incandescent lights but with the flashes controlled by thermal interrupters added to the circuitry. As a result, the composition - like the one shown below, a piece Malina titled Jazz - changed over several minutes.

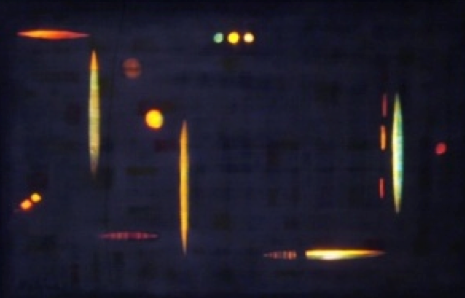

Malina wanted increased contrast between the moiré patterns made via wire mesh and their backgrounds. Getting frustrated, he tried back-lighting his works. The effect gave him a "feeling of ecstasy that one experiences” when "making a discovery.” This led to a series of experiments with low wattage bulbs behind compositions of superimposed painted wire mesh. Malina began to call his new works “electro-paintings.”In the months that followed, Malina increased his pace of experimentation. He started a new series of electro-paintings, using incandescent lights but with the flashes controlled by thermal interrupters added to the circuitry. As a result, the composition - like the one shown below, a piece Malina titled Jazz - changed over several minutes. As the title suggests, Jazz was meant to have a certain rhythm, something Malina said was especially noticeable when "viewed while listening to music with a rapid tempo.” I spent an evening a few years ago, watching Jazz at the Malina family's Paris apartment…even without some bebop playing, it created a dynamic yet contemplative mood.Malina's success encouraged him to think more about incorporating actual motion into his works. The electrical systems he was working with were starting to become more complex so he began to collaborate with assistants, including Jean Villmer, a young electronics engineer. They first tried working with systems with varying light output.

As the title suggests, Jazz was meant to have a certain rhythm, something Malina said was especially noticeable when "viewed while listening to music with a rapid tempo.” I spent an evening a few years ago, watching Jazz at the Malina family's Paris apartment…even without some bebop playing, it created a dynamic yet contemplative mood.Malina's success encouraged him to think more about incorporating actual motion into his works. The electrical systems he was working with were starting to become more complex so he began to collaborate with assistants, including Jean Villmer, a young electronics engineer. They first tried working with systems with varying light output. This proved excessively complicated and Villmer suggested an alternate approach: an electromechanical system that would give the visual effect of continuous movement combined with changing light. Malina experimented with this approach for years and even patented it. Along the way, he made over 200 electro-kinetic paintings, including (my favorite piece) Cosmos from 1965.

This proved excessively complicated and Villmer suggested an alternate approach: an electromechanical system that would give the visual effect of continuous movement combined with changing light. Malina experimented with this approach for years and even patented it. Along the way, he made over 200 electro-kinetic paintings, including (my favorite piece) Cosmos from 1965. By the time he died in 1981, Malina had created over 2600 works of art. These ranged from simple sketches and paintings to complex pieces that combined light, motion, and sound into - using the language popular at the time - a cybernetic system. His techniques fit with both the 1960s Op Art style as well as the kinetic art movement of the mid-20th century.A museum curator recently asked me if Malina was an important artist. I'm not an art historian and I'm uninterested such judgments. But we know Malina was a professional artist, selling dozens of works and participating in scores of group and solo shows in the US and Europe. What especially intrigues me about Malina are the different roads he took during his life - from pioneering rocketeer to championing science as a force for international cooperation to artist and then publisher at the art-science interface. In retrospect, we can see how these choices and options complemented and built on one another.There is some irony inherent in Malina's choices and the contingencies around them. He chose a new research trajectory in the 1930s because he wanted to build rockets for peaceful scientific research. But military interest during World War Two provided the necessary resources and the arena to demonstrate rocketry's potential. Malina quit building rockets in 1946 because he could foresee their destructive potential. Nonetheless, Aerojet, the company Malina helped start, made rocket motors that powered weapons of mass destruction. FBI pressure on Malina was motivated by the Cold War politics yet the same twilight conflict drove Aerojet's stock ever higher, enabling, maybe encouraging, Malina to follow a new road as an artist.

By the time he died in 1981, Malina had created over 2600 works of art. These ranged from simple sketches and paintings to complex pieces that combined light, motion, and sound into - using the language popular at the time - a cybernetic system. His techniques fit with both the 1960s Op Art style as well as the kinetic art movement of the mid-20th century.A museum curator recently asked me if Malina was an important artist. I'm not an art historian and I'm uninterested such judgments. But we know Malina was a professional artist, selling dozens of works and participating in scores of group and solo shows in the US and Europe. What especially intrigues me about Malina are the different roads he took during his life - from pioneering rocketeer to championing science as a force for international cooperation to artist and then publisher at the art-science interface. In retrospect, we can see how these choices and options complemented and built on one another.There is some irony inherent in Malina's choices and the contingencies around them. He chose a new research trajectory in the 1930s because he wanted to build rockets for peaceful scientific research. But military interest during World War Two provided the necessary resources and the arena to demonstrate rocketry's potential. Malina quit building rockets in 1946 because he could foresee their destructive potential. Nonetheless, Aerojet, the company Malina helped start, made rocket motors that powered weapons of mass destruction. FBI pressure on Malina was motivated by the Cold War politics yet the same twilight conflict drove Aerojet's stock ever higher, enabling, maybe encouraging, Malina to follow a new road as an artist. Would Malina have become a professional artist were it not for the FBI's harassment or in the absence of his financial independence? That's hard to say. But, unlike Frost's traveler in the woods confronting two seemingly equal routes, Malina expressed no regrets about the roads he took and those he wandered away from. ((The research for this blog post was done while I was the Lindbergh Chair at the National Air and Space Museum in 2015-2016. I'd also like to acknowledge a giant debt to three other researchers interested in Malina's life: Fraser MacDonald, Ewen Chardronnet, and Fabrice Lepelletrie.))

Would Malina have become a professional artist were it not for the FBI's harassment or in the absence of his financial independence? That's hard to say. But, unlike Frost's traveler in the woods confronting two seemingly equal routes, Malina expressed no regrets about the roads he took and those he wandered away from. ((The research for this blog post was done while I was the Lindbergh Chair at the National Air and Space Museum in 2015-2016. I'd also like to acknowledge a giant debt to three other researchers interested in Malina's life: Fraser MacDonald, Ewen Chardronnet, and Fabrice Lepelletrie.))