Art at the Speed of Light

After physicists first demonstrated the optical laser in May 1960, scientists and engineers started thinking of what they could do with it. So did artists. By 1970, these communities, often collaborating with one another, transformed lasers into a novel artistic medium. For a short period, Elsa M. Garmire was part of the artist-engineer interactions that peaked in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Raised by her chemical engineer father and her homemaker/violin teacher mother, by the age of 12 Garmire wanted to be a scientist. After doing an undergrad degree at Radcliffe, she started graduate school in MIT's physics program. Her specialty was optics and lasers and she was advised by Charles Townes, MIT's new provost who had shared the 1964 Nobel for his laser and maser research.

For a short period, Elsa M. Garmire was part of the artist-engineer interactions that peaked in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Raised by her chemical engineer father and her homemaker/violin teacher mother, by the age of 12 Garmire wanted to be a scientist. After doing an undergrad degree at Radcliffe, she started graduate school in MIT's physics program. Her specialty was optics and lasers and she was advised by Charles Townes, MIT's new provost who had shared the 1964 Nobel for his laser and maser research. In 1966, Garmire moved to California for a postdoctoral position at Caltech. Caring for two young children, increasingly unhappy with her marriage, and stymied by the school’s treatment of women faculty, Garmire began to consider other options.Intrigued by the use of technology “in a non-logical, artistic way” she contacted Billy Klüver in the summer of 1968. An engineer at Bell Labs, Klüver was the driving force behind Experiments in Art and Technology, the most prominent of the American organizations started in the 1960s to catalyze artist-engineer collaborations. Impressed with Garmire's enthusiasm and background - Klüver did laser research too - he brought her into the E.A.T. fold.An active member of E.A.T.'s branch in Los Angeles, Garmire organized, for example, a “Cybernetic Moon Landing Celebration” in July 1969 at Caltech. This included a "laser wall" Garmire helped build - a low-power argon laser beam spread into multiple lines of color that people could walk through.

In 1966, Garmire moved to California for a postdoctoral position at Caltech. Caring for two young children, increasingly unhappy with her marriage, and stymied by the school’s treatment of women faculty, Garmire began to consider other options.Intrigued by the use of technology “in a non-logical, artistic way” she contacted Billy Klüver in the summer of 1968. An engineer at Bell Labs, Klüver was the driving force behind Experiments in Art and Technology, the most prominent of the American organizations started in the 1960s to catalyze artist-engineer collaborations. Impressed with Garmire's enthusiasm and background - Klüver did laser research too - he brought her into the E.A.T. fold.An active member of E.A.T.'s branch in Los Angeles, Garmire organized, for example, a “Cybernetic Moon Landing Celebration” in July 1969 at Caltech. This included a "laser wall" Garmire helped build - a low-power argon laser beam spread into multiple lines of color that people could walk through. Garmire captured her thoughts on the relationship between art and technology in a short piece published in a newsletter the local E.A.T. chapter put out. “Technological art,” she wrote, “is the first step toward eliminating this divinity of technological wonders…The technological artist approaches and utilizes the incomprehensible for his own ends in ways often irrelevant to the original ‘purpose’ of the device.” ((Elsa Garmire, “Art and Technology: Ruminations of an Engineer,” E.A.T. L.A. #1, January 1970, p. 5.))

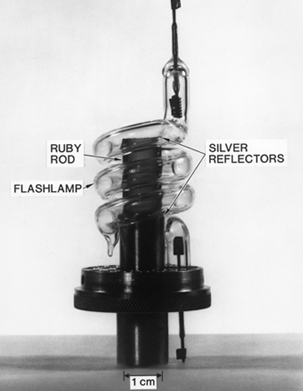

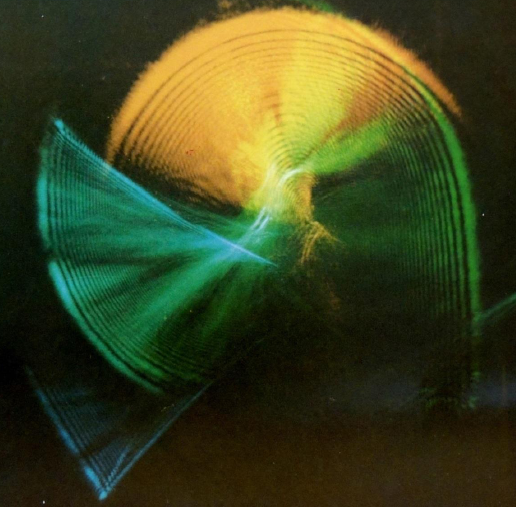

Garmire captured her thoughts on the relationship between art and technology in a short piece published in a newsletter the local E.A.T. chapter put out. “Technological art,” she wrote, “is the first step toward eliminating this divinity of technological wonders…The technological artist approaches and utilizes the incomprehensible for his own ends in ways often irrelevant to the original ‘purpose’ of the device.” ((Elsa Garmire, “Art and Technology: Ruminations of an Engineer,” E.A.T. L.A. #1, January 1970, p. 5.)) Garmire, working in her Caltech lab, became increasingly interested in exploring the aesthetic possibilities of lasers. Initially, Garmire created “lasergrams” – still photographs made by shining laser beams through various diffraction media. Here's one example from 1969. It's similar in appearance to the active, changing Lumia pieces made by the Danish-born artist Thomas Wilfred.

Garmire, working in her Caltech lab, became increasingly interested in exploring the aesthetic possibilities of lasers. Initially, Garmire created “lasergrams” – still photographs made by shining laser beams through various diffraction media. Here's one example from 1969. It's similar in appearance to the active, changing Lumia pieces made by the Danish-born artist Thomas Wilfred. Another Garmire creation from the same period is less diffuse and more geometric in shape:

Another Garmire creation from the same period is less diffuse and more geometric in shape: Caltech’s public relations department generated attention for her artwork in 1971. Unfortunately, a powerful earthquake on the day of Garmire’s opening at a local gallery overshadowed the publicity and also damaged some of her pieces.

Caltech’s public relations department generated attention for her artwork in 1971. Unfortunately, a powerful earthquake on the day of Garmire’s opening at a local gallery overshadowed the publicity and also damaged some of her pieces. Garmire also explored a variation on photographing manipulated laser images via live shows using a HeNe laser and rotating diffraction wheels and then filming the changing shapes and colors.

Garmire also explored a variation on photographing manipulated laser images via live shows using a HeNe laser and rotating diffraction wheels and then filming the changing shapes and colors. The idea of doing live laser shows was already in the air in the late 1960s. For example, Lowell Cross, a multi-media artist, performed the first “public multi-color laser light show” in May 1969 at Mills College. Cross later collaborated with Berkeley physicist Carson D. Jeffries and composer David Tudor to create a laser light show for the interior of the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo '70 in Osaka. This used a laser deflection system which manipulated the four colors from a krypton laser. Highly sensitive mirrors in the system could vibrate up to rates of 500 times per second and were activated from the sound system in the Pavilion's mirror dome.

The idea of doing live laser shows was already in the air in the late 1960s. For example, Lowell Cross, a multi-media artist, performed the first “public multi-color laser light show” in May 1969 at Mills College. Cross later collaborated with Berkeley physicist Carson D. Jeffries and composer David Tudor to create a laser light show for the interior of the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo '70 in Osaka. This used a laser deflection system which manipulated the four colors from a krypton laser. Highly sensitive mirrors in the system could vibrate up to rates of 500 times per second and were activated from the sound system in the Pavilion's mirror dome. Cross' work was only one example of attempts by professional artists to adapt the laser for aesthetic purposes. Another notable effort was by Rockne Krebs, an American artist who made laser-based sculptures for several years starting in the late 1960s.

Cross' work was only one example of attempts by professional artists to adapt the laser for aesthetic purposes. Another notable effort was by Rockne Krebs, an American artist who made laser-based sculptures for several years starting in the late 1960s. Over time, Krebs expanded his focus from small-scale efforts using lasers in rooms and galleries to ambitious outdoor installations that incorporated building and landscapes into the work. Harking back - unconsciously, most likely - to Garmire's experiments, his piece The Green Hypotenuse (1983) used a 7 mile-long laser beam that stretched from the observatory on Mt. Wilson down to Caltech.

Over time, Krebs expanded his focus from small-scale efforts using lasers in rooms and galleries to ambitious outdoor installations that incorporated building and landscapes into the work. Harking back - unconsciously, most likely - to Garmire's experiments, his piece The Green Hypotenuse (1983) used a 7 mile-long laser beam that stretched from the observatory on Mt. Wilson down to Caltech. A key difference between Garmire's "lasergrams" and installations made by artists like Krebs is the latter's ephemeral nature. When the laser was turned off, the art disappeared. All that's left are the sketches that went into its planning - "drawings for sculpture you can walk through" according to the title for one Krebs' exhibit.Physicist Garmire's experiments in blending art and technology were only slightly less ephemeral. In 1973, she co-taught a course on art and technology to undergrads at Caltech before leaving on a lengthy sabbatical trip with her family. By 1975, she was a single parent trying to return to a career in science. She did this with a vengeance. She held faculty positions at USC and then Dartmouth, eventually becoming dean of engineering there. Along the way, she made a point to promote the professional activities of women in science and engineering fields.

A key difference between Garmire's "lasergrams" and installations made by artists like Krebs is the latter's ephemeral nature. When the laser was turned off, the art disappeared. All that's left are the sketches that went into its planning - "drawings for sculpture you can walk through" according to the title for one Krebs' exhibit.Physicist Garmire's experiments in blending art and technology were only slightly less ephemeral. In 1973, she co-taught a course on art and technology to undergrads at Caltech before leaving on a lengthy sabbatical trip with her family. By 1975, she was a single parent trying to return to a career in science. She did this with a vengeance. She held faculty positions at USC and then Dartmouth, eventually becoming dean of engineering there. Along the way, she made a point to promote the professional activities of women in science and engineering fields. Professional accolades accrued - election to the National Academy of Engineering and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She was also made a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, the American Physical Society, and the Optical Society of America (she served as OSA's president in 1993). A new husband, her two kids, and her scientific career - these, instead of art, became the lights of her life.

Professional accolades accrued - election to the National Academy of Engineering and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She was also made a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, the American Physical Society, and the Optical Society of America (she served as OSA's president in 1993). A new husband, her two kids, and her scientific career - these, instead of art, became the lights of her life.