The Future, 50 Years Ago

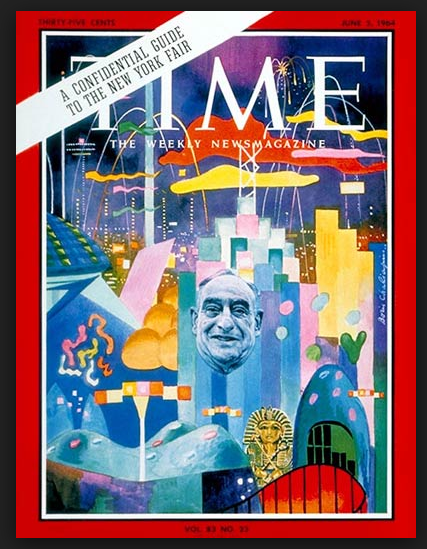

Last week, the Pew Research Center released a report that surveyed Americans' attitudes about technology and their thoughts about what technological advances would happen in the next half-century. I'll be writing something about the report itself later - suffice it to say for now that Americans' views of the technological future are remarkably static. But Pew's report was quite timely because, 50 years ago, the New York World's Fair opened.The juxtaposition, while surely accidental, prompted me to go back and revisit how people a half-century ago thought about technology and the future. So, climb into your TARDIS of choice and let's go back to Flushing Meadow in 1964 --On a drizzly spring day in 1964, some 92,000 people arrived by car, subway, and helicopter at a former swampy ash dump across the East River. They came to visit the future. They found it spread out over a 646 acre park dotted with lakes, lagoons, and reflecting pools. There, after paying $2, visitors entered the New York World’s Fair, hopped aboard air-conditioned monorail trains, and strolled amidst a colorful medley of domes, fins, pylons, and cubes fashioned from plastic, aluminum, glass, and concrete.At the Fair’s official dedication, a teenaged Boy Scout from Queens Troop 183 joined President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Federal Pavilion with its façade of glittering colored glass and massive staircases. From here they could see the Unisphere, a 450-ton stainless steel model of the earth rising twelve stories over Flushing Meadow that became the Fair’s iconic symbol.

Last week, the Pew Research Center released a report that surveyed Americans' attitudes about technology and their thoughts about what technological advances would happen in the next half-century. I'll be writing something about the report itself later - suffice it to say for now that Americans' views of the technological future are remarkably static. But Pew's report was quite timely because, 50 years ago, the New York World's Fair opened.The juxtaposition, while surely accidental, prompted me to go back and revisit how people a half-century ago thought about technology and the future. So, climb into your TARDIS of choice and let's go back to Flushing Meadow in 1964 --On a drizzly spring day in 1964, some 92,000 people arrived by car, subway, and helicopter at a former swampy ash dump across the East River. They came to visit the future. They found it spread out over a 646 acre park dotted with lakes, lagoons, and reflecting pools. There, after paying $2, visitors entered the New York World’s Fair, hopped aboard air-conditioned monorail trains, and strolled amidst a colorful medley of domes, fins, pylons, and cubes fashioned from plastic, aluminum, glass, and concrete.At the Fair’s official dedication, a teenaged Boy Scout from Queens Troop 183 joined President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Federal Pavilion with its façade of glittering colored glass and massive staircases. From here they could see the Unisphere, a 450-ton stainless steel model of the earth rising twelve stories over Flushing Meadow that became the Fair’s iconic symbol. Together, they cut the ribbon that officially opened the extravaganza’s international plazas and corporate exhibit halls. Over the sporadic voices of civil rights protestors, Johnson reminded listeners of the remarkable progress scientists and engineers had made since New York hosted a World’s Fair on the eve of World War Two. In 1939, Johnson reflected, few people would have predicted an era of space travel, global communication via satellites, wonder drugs and organ transplants, and the promise of nuclear power. But, as sodden flags moved limply in the chill breeze, Johnson warned that recently technological progress displayed “two faces” and urged world leaders and researchers to “conquer conflict just as we have conquered science.”

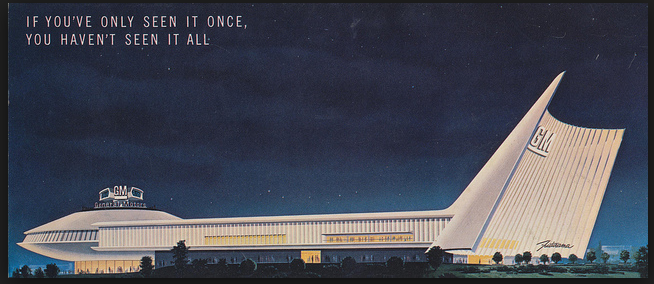

Together, they cut the ribbon that officially opened the extravaganza’s international plazas and corporate exhibit halls. Over the sporadic voices of civil rights protestors, Johnson reminded listeners of the remarkable progress scientists and engineers had made since New York hosted a World’s Fair on the eve of World War Two. In 1939, Johnson reflected, few people would have predicted an era of space travel, global communication via satellites, wonder drugs and organ transplants, and the promise of nuclear power. But, as sodden flags moved limply in the chill breeze, Johnson warned that recently technological progress displayed “two faces” and urged world leaders and researchers to “conquer conflict just as we have conquered science.” For the 51 million people who visited the Fair in 1964 and 1965, by far the most popular attraction was fully focused on the future. Each day Futurama received some 80,000 visitors who sat three-abreast in moving lounge chairs. From these perches, they saw “a brighter promise of things to come” yet “well on its way to tomorrow's world” as imagined by stylists at General Motors, the sponsor of the $50 million exhibit. ((The exhibit was officially called Futurama II to distinguish it from General Motors’ wildly popular Futurama ride at the 1939 New York World’s Fair but contemporary press coverage typically did not make the distinction.)) “Built around the idea that the human population has ample room to explode,” Futurama took its time travelers past carefully detailed dioramas that showed future cities that future people might build on new frontiers with future machines.

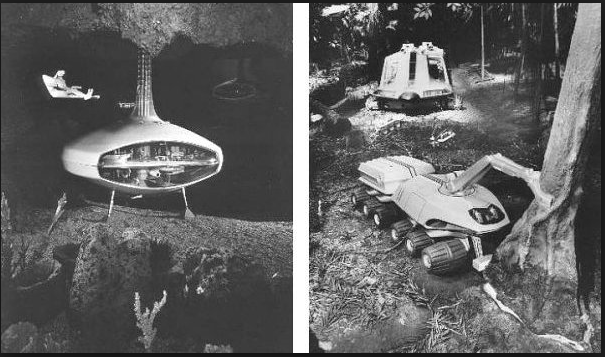

For the 51 million people who visited the Fair in 1964 and 1965, by far the most popular attraction was fully focused on the future. Each day Futurama received some 80,000 visitors who sat three-abreast in moving lounge chairs. From these perches, they saw “a brighter promise of things to come” yet “well on its way to tomorrow's world” as imagined by stylists at General Motors, the sponsor of the $50 million exhibit. ((The exhibit was officially called Futurama II to distinguish it from General Motors’ wildly popular Futurama ride at the 1939 New York World’s Fair but contemporary press coverage typically did not make the distinction.)) “Built around the idea that the human population has ample room to explode,” Futurama took its time travelers past carefully detailed dioramas that showed future cities that future people might build on new frontiers with future machines. The exhibit predicted new technologies that would enable future people to live wherever they wish, be this in isolated deserts, polar regions, remote mountain regions or at the ocean bottom. Travel to these regions, of course, would be key but General Motors proposed all manners of transportation alternatives from “aqua-copters” to ice-crawlers and nuclear-powered submarines. And if no highways existed, the world’s largest car maker was prepared to make them – one of the most talked about scenes in Futurama featured machines that would imaginably fell trees with laser beams, the foliage then gobbled up by massive road-building machine which extruded a mile of four-lane highway from its rear every hour. The new frontiers were not just for habitation and travel, however, but sites of production and extraction. The ocean floor had abundant minerals and plant life that could be harvested while the earth’s deserts, irrigated by vast desalination plants, could be turned into verdant farmland, a “science of plenty for a growing world.”

The exhibit predicted new technologies that would enable future people to live wherever they wish, be this in isolated deserts, polar regions, remote mountain regions or at the ocean bottom. Travel to these regions, of course, would be key but General Motors proposed all manners of transportation alternatives from “aqua-copters” to ice-crawlers and nuclear-powered submarines. And if no highways existed, the world’s largest car maker was prepared to make them – one of the most talked about scenes in Futurama featured machines that would imaginably fell trees with laser beams, the foliage then gobbled up by massive road-building machine which extruded a mile of four-lane highway from its rear every hour. The new frontiers were not just for habitation and travel, however, but sites of production and extraction. The ocean floor had abundant minerals and plant life that could be harvested while the earth’s deserts, irrigated by vast desalination plants, could be turned into verdant farmland, a “science of plenty for a growing world.” GM’s Futurama was only the Fair’s largest and most visible symbol of the dominant place that technology, especially corporate and government-created technology, occupied in mid-century American culture. American Express, IBM, and more than a dozen other major companies had similar future-oriented pavilions that extolled optimism, progress, and convenience that the consumer-oriented technologies of the 1960s brought. The Fair debuted in the same era when The Jetsons presented a technological cartoon utopia of robot servants, three-day workweeks, and flying cars. For many fairgoers, the two presented interchangeable visions of the future.Even with its enthusiastic, even Panglossian, expressions of faith in technology and corporate futurism, cracks were visible in the Fair’s ideological façade. Johnson’s dedication speech acknowledged that in the realm of science and technology, “reality has far-outstripped the vision” and suggested some temperance in what scientists and engineers could or should accomplish. The Fair’s motto “Peace through Understanding” surely struck many as questionable in a year when the global nuclear stockpile topped 36,000.

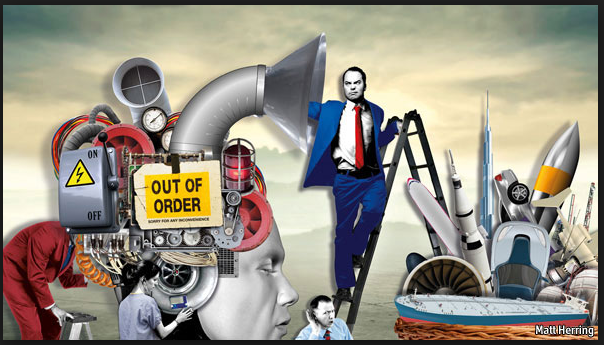

GM’s Futurama was only the Fair’s largest and most visible symbol of the dominant place that technology, especially corporate and government-created technology, occupied in mid-century American culture. American Express, IBM, and more than a dozen other major companies had similar future-oriented pavilions that extolled optimism, progress, and convenience that the consumer-oriented technologies of the 1960s brought. The Fair debuted in the same era when The Jetsons presented a technological cartoon utopia of robot servants, three-day workweeks, and flying cars. For many fairgoers, the two presented interchangeable visions of the future.Even with its enthusiastic, even Panglossian, expressions of faith in technology and corporate futurism, cracks were visible in the Fair’s ideological façade. Johnson’s dedication speech acknowledged that in the realm of science and technology, “reality has far-outstripped the vision” and suggested some temperance in what scientists and engineers could or should accomplish. The Fair’s motto “Peace through Understanding” surely struck many as questionable in a year when the global nuclear stockpile topped 36,000. While the coming months would see Robert Moses’ promised land blasted for financial scandal and its failure to turn a profit, critics complained of its “tacky, plastic, here-today-blown-tomorrow look.” Indeed, cultural observers decried the Fair’s very imagining of the future. A journalist for Time noted that the corporate and government exhibitors “displays not what might be done in the future but rather what has already been done…The 1939 fair was a promise. The 1964 fair is a boast.”Comments such as these were not just isolated barbs from journalists. By the time the New York World’s Fair closed in October 1965, there was a growing sense of unease and skepticism about whether technology, especially that promulgated by government programs and corporate research labs, was an unalloyed force for good. General Motors, for example, closed its popular Futurama pavilion in the same year that a young consumer crusader named Ralph Nader blasted the “designed-in dangers” of that company’s cars in his book Unsafe at Any Speed. By the end of the decade, this general sense of ambivalence transformed into widespread pessimism, especially among intellectuals and cultural critics. For many Americans, the scenarios suggested by Futurama and other fair exhibits weren’t just banal and boring – they were threatening.When Gay Talese, then a young New York City reporter in the 1960s, made a point of interviewed elderly visitors to the Fair, he and was to find that many had also visited the 1939-40 World's Fair which opened at the same site on the eve of World War Two. “I was so skeptical,” a retired school teacher said, “at the 1939 fair when they showed us all those rockets.” Another chimed in, “And television!” Those who took the 15 minute ride through Futurama, received a small blue and white lapel button. It proclaimed: “I have seen the future.” And then they returned to the Fair, squinting into the bright and persistent glare of the present...

While the coming months would see Robert Moses’ promised land blasted for financial scandal and its failure to turn a profit, critics complained of its “tacky, plastic, here-today-blown-tomorrow look.” Indeed, cultural observers decried the Fair’s very imagining of the future. A journalist for Time noted that the corporate and government exhibitors “displays not what might be done in the future but rather what has already been done…The 1939 fair was a promise. The 1964 fair is a boast.”Comments such as these were not just isolated barbs from journalists. By the time the New York World’s Fair closed in October 1965, there was a growing sense of unease and skepticism about whether technology, especially that promulgated by government programs and corporate research labs, was an unalloyed force for good. General Motors, for example, closed its popular Futurama pavilion in the same year that a young consumer crusader named Ralph Nader blasted the “designed-in dangers” of that company’s cars in his book Unsafe at Any Speed. By the end of the decade, this general sense of ambivalence transformed into widespread pessimism, especially among intellectuals and cultural critics. For many Americans, the scenarios suggested by Futurama and other fair exhibits weren’t just banal and boring – they were threatening.When Gay Talese, then a young New York City reporter in the 1960s, made a point of interviewed elderly visitors to the Fair, he and was to find that many had also visited the 1939-40 World's Fair which opened at the same site on the eve of World War Two. “I was so skeptical,” a retired school teacher said, “at the 1939 fair when they showed us all those rockets.” Another chimed in, “And television!” Those who took the 15 minute ride through Futurama, received a small blue and white lapel button. It proclaimed: “I have seen the future.” And then they returned to the Fair, squinting into the bright and persistent glare of the present...