Astronomy's History Trap

Last week, I wrote a blog post about the National Science Foundation's plan to close several optical and radio telescopes as a cost-cutting measure. It clearly hit a nerve. Thanks largely to a reposting from Physics Today, more people - some 2200 - read this, more than any other I've written. (Only my chiding of Michio Kaku drew a similar number of readers). In response, several people wrote to me and noted the current plans in the United States to build a new optical telescope facility with light collecting area equivalent to a 30-meter mirror. Here's my take on this...There is quote typically attributed to Mark Twain that says, "History doesn't repeat itself; but it does rhyme." Regardless of whether Mr. Clemens actually said this, the fact is that astronomers today should be hearing all sorts of rhyming. But many aren't and therein lies the problem. There are two contenders for ground-based astronomy's next big machine. The "Thirty Meter Telescope" project is spearheaded by scientists from Caltech and my own school, the University of California; institutions in India, Japan, China, and Canada also pledging funds to build it on Mauna Kea in Hawai'i. The heart of the telescope's design is 492 mirror segments, each 1.45 meters in size, that would create a mosaic-like light collecting surface. Cost? Somewhere between $970 million and $1.2 billion. The Moore Foundation (started by Intel co-founder Gordin Moore) has so far pledged $250 million toward the TMT.

There are two contenders for ground-based astronomy's next big machine. The "Thirty Meter Telescope" project is spearheaded by scientists from Caltech and my own school, the University of California; institutions in India, Japan, China, and Canada also pledging funds to build it on Mauna Kea in Hawai'i. The heart of the telescope's design is 492 mirror segments, each 1.45 meters in size, that would create a mosaic-like light collecting surface. Cost? Somewhere between $970 million and $1.2 billion. The Moore Foundation (started by Intel co-founder Gordin Moore) has so far pledged $250 million toward the TMT.

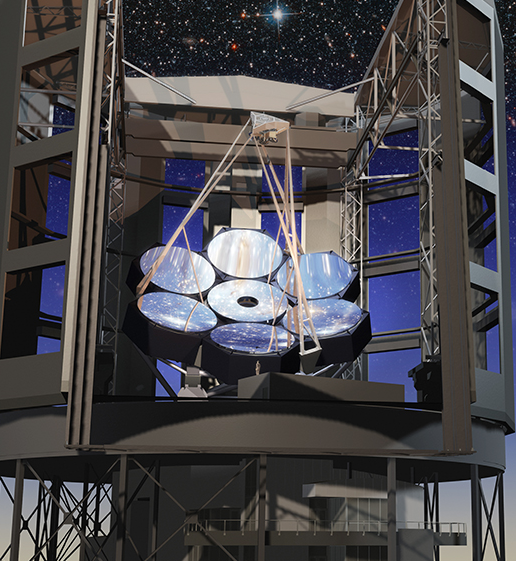

Going head-to-head with the TMT is the Giant Magellan Telescope. Planned for a mountain site in Chile, the GMT's cost is about the same as low-end estimates for the TMT. But the GMT's design is radically different. It will instead use seven massive 8.4-meter mirrors to create the equivalent of a 30-meter telescope. ((Three of these have so far been cast at the Mirror Lab at the University of Arizona.)) The GMT consortium includes the Carnegie Institution of Science, Harvard, the Smithsonian, the University of Arizona, and several more.

It's at this point that we should start to hear the rhyming sounds of history. Because thirty years ago, American astronomers were in exactly the same spot. And, from what I can tell, they didn't learn as much as they could have from the experience.

To wit: In the mis-1970s, the American astronomy community was in crisis. The traditional design model for large telescopes, based on the 200-inch Hale telescope on California’s Palomar Mountain, could no longer satisfy the financial constraints on and research expectations of the U.S. astronomy community. At the same time, the nation’s large telescopes were increasingly over-subscribed; simply observing faint objects for longer times was not feasible logistically.

Several ways forward were proposed. Kitt Peak National Observatory even developed initial designs for a 25-meter Next Generation Telescope.

When the 25-meter proved too ambitious, the national observatory scaled plans back to 15 meters. The problem? There were two competing designs for what was then called the National New Technology Telescope...is this starting to sound familiar?

Plan #1 - Build a telescope with a 15-meter light collecting area using 60 individual hexagonal glass segments to form the light collecting area. This design was championed by, yes, astronomers from Caltech and the University of California.

Plan #2 - Or...put four 7.5 meter mirrors on a common mount to create a total light gathering ability of a 15-meter telescope. This effort was pushed by researchers at - wait for it - the University of Arizona.

Are you hearing those echoes of the past yet?

So, what happened to the NNTT? At a meeting in July 1984, a blue ribbon panel of astronomers and engineers picked Arizona's multiple-mirror design. But it was a Pyrrhic victory. Less than a year later, the W.M. Keck Foundation gave Caltech $70 million to build a 10-meter telescopes in Hawai'i; funding to build a second followed. ((All of this history is detailed in my 2004 book Giant Telescopes; some of it is captured in this article.))

Meanwhile, NSF funding for the "victorious" NNTT was nowhere near as generous and, in 1987, the 15-meter national telescope project was killed. What arose from the ashes of the national 15-meter project was an international partnership to build two 8-meter telescopes. The first Gemini telescope in Hawai'i saw first light in 1999; its twin in Chile reached the same milestone in 2000. The result of all this astro-politicking: two privately operated 10-meter telescopes and two publicly accessible 8-meter telescopes. ((The whole story is way more complicated that I've summarized here. For example, Arizona's mirror technology wasn't used in either Keck or Gemini. Rather, it was used for the twin Magellan telescopes in Chile and the NNTT design was used, sort of, to build the Large Binocular Telescope in southern Arizona. Meanwhile, the Gemini telescopes were built using what are called "thin meniscus mirrors," a third technological path that emerged in the 1980s.))

Today's impasse over whether to build the TMT, the GMT, both, et cetera closely resembles the debates in the early 1980s about the National New Technology Telescope. To be sure, the past isn't exactly repeating. Neither TMT nor GMT is envisioned as a publicly accessible facility. But the history does rhyme. Many of the actors (individuals as well as institutions) that were so embroiled in that controversy/competition over how to best build today's giant telescopes are implicated in today's debates about which design and which partnership model is best for tomorrow's bigger (gianter?) telescopes. (One quickly runs out of superlatives...large, overwhelmingly large, monster, etc...meanwhile, the European Southern Observatory's its 40-meter mega-project with the anodyne name of the Extremely Large Telescope.)

Why should this ancient history - water under the bridge, one might say - matter to astronomers today? I can think of at least three reasons:#1 - A billion dollars to build a new telescope - whether it comes from private donors or governments - is obviously a lot of money. This is thrice true when we're talking about possibly building three 30-meter class facilities. If this means shuttering smaller 'scopes, as the NSF is planning, than one has to consider the impact this could have on astronomy's "have-nots" i.e. those people without access to privately-operated facilities. ((Obviously, my splitting an entire scientific community into two camps is an oversimplification. There are researchers from Caltech who use the National Radio Astronomy Observatory's 'scopes just as "have-nots" can sometimes compete for time at privately-operated Keck telescopes. The NSF even operated the "Telescope System Instrumentation Program" which would help fund "the development of instruments...for the private observatories, in exchange for which telescope time on those facilities will be made available to the community." It's unclear to me whether TSIP is still operating...The National Optical Astronomy Observatory's page for the program doesn't seem to have been updated recently...another NOAO page suggests that time is available in 2014 though. This page, however, has some interesting stats on the number of nights made available and the estimated costs.)) Will ever-larger research facilities affect how science is done? How many grad students or postdocs will have access to a 30-meter facility? Would they simply become folded into a much larger research program? The current generation of 8/10-meter class facilities clearly changed the practice of doing science...there's every reason to expect 30-meter telescopes will do likewise.

#2 - History seems to be poised to repeat itself...In the 1980s, while the U.S. community bickered over which design was best (and tried to raise the capital necessary to start building), the European science community slowly and methodically built an innovative series of telescopes. The culmination of this was the Very Large Telescope (again, the names...). This suite of four 8-meter telescopes in Chile helped put European astronomy on equal (some would say better) footing than their U.S. counterparts. Now, I'm not trying to make some nationalistic argument here. Astronomical research in the 21st century is certainly more international than it was three decades ago while new players (China, India, et al.) have entered the telescope game. But astronomers with whom I have spoken warn of a similar dynamic at work now...while the U.S. community dithers over whether to build TMT, GMT, whatever, the European community is gradually making progress towards its 40-meter goal. Americans' fear is that their European competitors will be able to pick the low-hanging "astronomy fruit" that a new giant facility will put in reach.

#3 - Perhaps the most critical reason for thinking about all of this "history" is how today's debates over which telescope to build affect the morale and spirit of the American astronomy community. How does this infighting reflect the community's moral economy i.e. those unstated yet accepted rules that define and structure community interactions? The principal actors driving the TMT and GMT projects forward are leaders in the astrophysics community. How much energy and effort is being spent in sparring with one another and touting the benefits of one's own design (and disparaging the neighbor's). To a naif, this battling can seem downright ridiculous. Caltech and Carnegie are a few miles apart yet there might as well be a shark-filled canyon between them given the vitriolic statements I've heard from the two camps. The only point of agreement seems to be how the NSF has failed to provide necessary and adequate leadership in helping the U.S. get its act together.

Now, one could, of course, argue that a lesson to take away from all of this history is that it all turned out fine in the end. Keck was built, Gemini was built, et cetera...maybe the "market" for telescopes worked and things just naturally sorted themselves out. Maybe competition was a good thing...

But I am inclined to think it all worked in spite of things. More to the point, I think astronomers need to recognize how their history is rhyming and consider how not to repeat past mistakes. As I wrote this blog post, I kept thinking of how much of today's circumstances resemble the situations I described in my book which is now already a decade old...but, as André Gide noted, “Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.”