Robert Heinlein and the Harsh Politics of Science Fiction

Of all the archives I worked with when writing The Visioneers, none was more intriguing than the collection of Robert A. Heinlein's papers. Heinlein's death a quarter-century ago coupled with my recent thoughts on the interplay between science fiction and politics nudged me back to these papers for a second look.

Set up as a cooperative project between the Special Collections at University of California, Santa Cruz and the Heinlein Prize Trust, the Heinlein archives is a very cool on-line collection. Rather than having to travel to UC-Santa Cruz, researchers can browse and download PDF copies of Heinlein's notes, research, early drafts, and published works. Not only is it convenient but it offers an opportunity to explore the creative processes of one of the greatest sci-fi writers in history.

But there's a catch. As Heinlein popularized in his 1966 libertarian-treatise-as-science fiction-book The Moon is a Harsh Mistress --- TANSTAAFL. Translated: There ain't no such thing as a free lunch. So, when it comes to downloading materials from the Heinlein archive, there's no free lunch. Downloading a few hundred pages of materials costs just a few bucks - way cheaper than having to visit the archive in person. ((UC-SC still maintains physical copies of the collection which can be viewed for free at its campus.))

But I think there is a larger moral principle at work here...to understand this, you need to know a little more about Heinlein's own political views. Some of these can be teased out from his published sci-fi writings. For example, his 1959 book Starship Troopers won a Hugo award (1960) but was also harshly attacked for its right-wing - some even said fascist - vision of a world run according to strict military order. (Heinlein himself did a stint in the Navy - as an aviation engineer - as did his third and long-term wife Virginia).

Two years later, Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land veered in a totally different political and cultural direction. Questioning all sorts of religious and sexual conventions, Stranger was also a Hugo winner. With characters who live in communes and practice group sex, the book became a touchstone of sorts for the burgeoning counterculture of the 1960s.

Not all readers were entranced. A New York Times critic - writing before sci-fi had become an acceptable/respectable genre - called it "puerile and ludicrous" in which a "non-stop orgy is combined with a lot of preposterous chatter." ((Orville Prescott. "Books of The Times". The New York Times. August 4, 1961, p. 19)) Nevertheless, it sold over 3 million copies.

Although shades of Heinlein's true political leanings - libertarian in the classic sense - could be found in Troopers and Stranger, these were revealed much more clearly in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (yes, another Hugo winner). Originally titled The Brass Cannon, the novel's plot centers around a lunar colony's revolt against its Earth-based government overseers. At the same time, the novel champions free-market - emphasis on free - and private enterprise. ((In a 1973 interview with the libertarian writer J. Neil Schulman, Heinlein questioned whether free markets were more efficient. "The justification," he said, "for free enterprise is not that it's more efficient, but that it's free.")) Heinlein's "unprecedented combination of rocket visions" with "tough-minded individualism respectful of the military and iconoclastic free living" led Brian Doherty, a senior editor at the libertarian magazine Reason, to call Heinlein a true "bard of Southern California" who anticipated the Golden State's political and cultural shifts. ((A 2007 essay by Doherty expands on these ideas very nicely.)) Given the role that California played in 70s-era national politics - anti-tax revolt, the rise of suburban Republicans, the religious right that spun out of the counterculture - these views are critically important for understanding the last 30 years of U.S. history.

While I "visited" the Heinlein archives, I certainly detected signs of Heinlein's libertarian views that spoke to both the political left and right. I was also intrigued by how Heinlein imagined the politics of future space settlements toward the end of his life. This made me wonder whether his libertarian ideas, forged decades earlier, resonated with either the formal libertarian political movement (which really began to gel in the US in the early 1970s) or the Reagan-era's focus on free markets and private enterprise. The answer was more complicated than I first imagined.

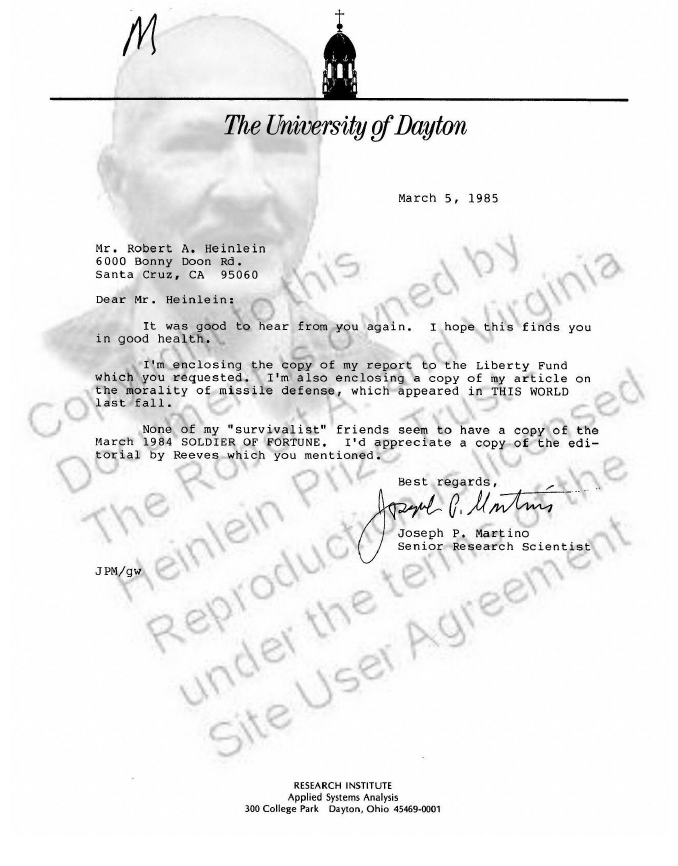

A sense of Heinlein's thinking can be found in an exchange of letters he had in 1985 with Dr. Joseph P. Martino, a retired Air Force colonel who was serving as a technology forecaster at the University of Dayton. Their exchange started with a discussion about the morality of missile defense.

Heinlein supported Reagan's SDI program unlike "the Sagans, the Asimovs, the Garvins, the Arthur Clarkes" and other "soft-minded fools who fantasize about a world that does not exist." (Odd words coming from a sci-fi writer but explicable in the context of their exchange.) Heinlein goes on to note that the debate over SDI had science fiction writers "more bitterly divided that it was over the war in Vietnam." In fact, the entire grassroots pro-space movement was divided on the same issue.

Like many people intrigued with the idea of settlements in space, Heinlein gave a lot of thought as to what off-world politics might be like. In this matter, he said he remained "both a pessimist and a lower-case libertarian." When it came to "our race's future in space," Heinlein predicted that those "who do not go into space will find, rather quickly, that they can neither control nor tax those who do."

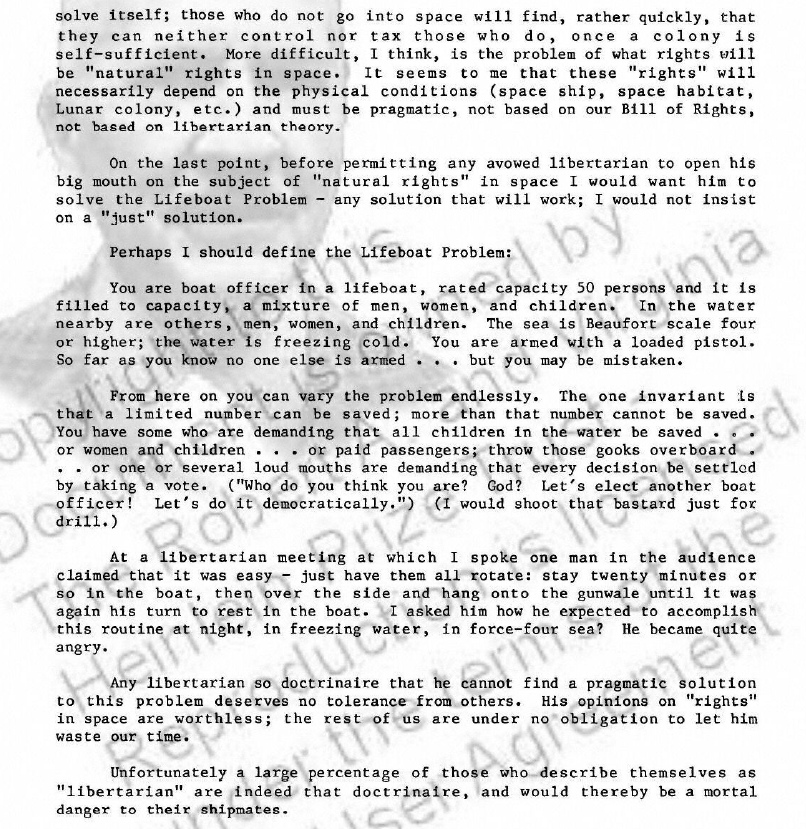

Heinlein goes on to make it clear that his political position was rested entirely on an unsentimental pragmatism and was "not based on our Bill of Rights" or "libertarian theory." A key test for the sci-fi writer was a person's proposed solution to what he called the Lifeboat Problem - what rights should an individual be accorded in a place where food, water, air, safety, etc. are in tenuous supply i.e. a submarine or a space colony? ((Here, it's quite likely Heinlein was influenced by the writings of University of California biologist Garrett Hardin who famously considered "lifeboat ethics" in the 1970s.)) In fact, he demanded a solution to this question before "any avowed libertarian" should be allowed "to open his big mouth on the subject of "natural rights" in space."

He framed the scenario thus: "You are boat officer in a lifeboat, rated capacity 50 persons and it is filled to capacity, a mixture of men, women, and children. In the water are others...The sea is Beaufort scale four or higher; the water is freezing cold. You are armed with a loaded pistol. So far as you know no one else is armed...but you may be mistaken." What do you do? Rotate people in and out of the life boat every 20 minutes and try to save everyone? Noble but impractical. Maybe someone would suggest taking a vote to which Heinlein said "I would shoot that bastard just for drill."

So far as libertarians enamored with theory and posturing - "Any libertarian so doctrinaire that he cannot find a pragmatic solution to this problem deserves no tolerance from others...Unfortunately a large percentage of those who describe themselves as "libertarians"...would be a a mortal danger to their shipmates."

One might read Heinlein's views here in several ways - maybe the grumblings of an octogenarian WW2 veteran...or perhaps they represent the thoughts of someone smitten with Reagan-era socioeconomic policies toward the poor (which would be ironic given Heinlein's early social activism as part of Upton Sinclair's "End Poverty in California" movement). Aside from their bluntness, what struck me most when I re-read Heinlein's statements was how they reminded me of another science fiction epic - the fantastic 2004-2009 re-make of Battlestar Galactica. One of the series' on-going themes, especially in the opening season, is the harsh yet pragmatic sacrifices the Colonial fleet has to make to ensure the survival of the greatest number of humans. Heinlein would have approved.

After his death in 1988, Heinlein's estate helped establish the Heinlein Prize Trust. It regularly gives out large cash awards "to encourage and reward progress in commercial space activities." The most recent award - $250,000 - went to SpaceX founder and libertarian-minded entrepreneur Elon Musk. One of Musk's ambitions is to establish a settlement for 80,000 people on Mars. So, I'm left wondering what his solution to Heinlein's Lifeboat problem would be?