Does Matter Still Matter?

We often want our new technologies to be "frictionless". We want them to reside elsewhere - consider the buzz over 'cloud' computing - and free from the thinginess that weighs down "traditional" technologies and industries. Perhaps this is an echo going back to the ancient Greek's exaltation of mind over matter. However, there have been attempts to think of technology in a more disembodied manner. For instance, in 1994, a manifesto of sorts appeared titled "Cyberspace and the American Dream: A Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age" Its authors were an eclectic bunch: Esther Dyson (daughter of physicist Freeman Dyson and an Internet entrepreneur), Alvin Toffler (pop futurist famous for books like Future Shock and The Third Wave); George Keyworth (Reagan's former science adviser and director at Hewlett-Packard); and George Gilder (a critic of feminism, a speech writer for Reagan, and - later - an advocate for intelligent design). Despite their varied backgrounds, the four co-authors were all techno-utopians who believed in the emancipatory power of both the Internet and the free market.Their preamble began with the memorable, if not hubristic, statement, "The central event of the 20th century is the overthrow of matter...The powers of mind are everywhere ascendant over the brute force of things." Out on the new cyber-frontier, the contours of cyberspace were just beginning to come into focus. ((For example, the first killer app for the Web, Netscape Navigator, was released just a few months after Dyson et al. shared their manifesto.)) Written in the giddy afterglow of the Cold War's end, the halcyon days of pets.com beckoned as the Internet bubble began to inflate.

Its authors were an eclectic bunch: Esther Dyson (daughter of physicist Freeman Dyson and an Internet entrepreneur), Alvin Toffler (pop futurist famous for books like Future Shock and The Third Wave); George Keyworth (Reagan's former science adviser and director at Hewlett-Packard); and George Gilder (a critic of feminism, a speech writer for Reagan, and - later - an advocate for intelligent design). Despite their varied backgrounds, the four co-authors were all techno-utopians who believed in the emancipatory power of both the Internet and the free market.Their preamble began with the memorable, if not hubristic, statement, "The central event of the 20th century is the overthrow of matter...The powers of mind are everywhere ascendant over the brute force of things." Out on the new cyber-frontier, the contours of cyberspace were just beginning to come into focus. ((For example, the first killer app for the Web, Netscape Navigator, was released just a few months after Dyson et al. shared their manifesto.)) Written in the giddy afterglow of the Cold War's end, the halcyon days of pets.com beckoned as the Internet bubble began to inflate. Today it's easy to look back on statements like the Magna Carta and marvel at its prescience as well as its utter naivete about the "overthrow of matter." A persistent flaw in cyber-advocates' 1990s boosterism was forgetting that all of the stuff that made the Internet and the Web work was, well, made of stuff. And to imply that all of this was nothing but potential emancipatory energy...workers in Silicon Valley, Seoul, and Shenzen would certainly see it differently. Similarly, today's server farms aren't running on good intentions while generating Google search results. To be sure, the Magna Carta's autors aimed at a deeper subtlety but their overall attitude was to denigrate the "desert of the real" in favor of the glory of cyberspace.

Today it's easy to look back on statements like the Magna Carta and marvel at its prescience as well as its utter naivete about the "overthrow of matter." A persistent flaw in cyber-advocates' 1990s boosterism was forgetting that all of the stuff that made the Internet and the Web work was, well, made of stuff. And to imply that all of this was nothing but potential emancipatory energy...workers in Silicon Valley, Seoul, and Shenzen would certainly see it differently. Similarly, today's server farms aren't running on good intentions while generating Google search results. To be sure, the Magna Carta's autors aimed at a deeper subtlety but their overall attitude was to denigrate the "desert of the real" in favor of the glory of cyberspace.

I recently read two things that made me revisit and rethink claims - some more than two decades old - about the "overthrow of matter." The first of these was George Packer's recent and excellent book The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America.

One of the characters journalist Packer follows as he traces the unraveling of American institutions and ideals since the 1970s is Silicon Valley hero and study-in-contrasts Peter Thiel. A German-born entrepreneur, Thiel made his fortune by co-funding PayPal (along with Elon Musk) and investing in, among other things, Facebook. Stanford educated, Thiel set up an (in)famous program to pay talented young people to quit college to "build the innovative companies of tomorrow." Owner of resplendent Bay Area properties, Thiel has given $1.25 million to the Seasteading Institute to help further its goal of establishing "permanent, autonomous ocean communities" - sea colonies - where libertarian principles will be put into action. And, despite his homosexuality, Thiel has donated money to political groups that are indifferent, if not hostile, to gay rights.

One of the characters journalist Packer follows as he traces the unraveling of American institutions and ideals since the 1970s is Silicon Valley hero and study-in-contrasts Peter Thiel. A German-born entrepreneur, Thiel made his fortune by co-funding PayPal (along with Elon Musk) and investing in, among other things, Facebook. Stanford educated, Thiel set up an (in)famous program to pay talented young people to quit college to "build the innovative companies of tomorrow." Owner of resplendent Bay Area properties, Thiel has given $1.25 million to the Seasteading Institute to help further its goal of establishing "permanent, autonomous ocean communities" - sea colonies - where libertarian principles will be put into action. And, despite his homosexuality, Thiel has donated money to political groups that are indifferent, if not hostile, to gay rights. Thiel, in Packer's account, has also given up on the future. Or at least the future as it was imagined in the 1950s. No space colonies, underwater cities, or extreme engineering projects. As one of Thiel's investment groups says in its prospectus, "We wanted flying cars. Instead we got a 140 characters." Pulling an iPhone from his pocket, Thiel tells Packer that it's no technological breakthrough. "The information age has made Thiel rich, but it has also been a disappointment to him," Packer writes, "The creation of virtual worlds has turns out to be no substitute for advances in the physical world." Jobs and wealth flow from improvements in manufacturing and industry, not just from shuffling electrons and dollars - the two are synonymous today - around the planet. And, to Thiel's liking, not enough attention is being paid to the moving around of atoms and molecules - traditional industry - as opposed to bytes. ((The fact that Thiel made his fortune via Internet ventures is an irony not lost on Packer or this reader.))In recent years, economists and entrepreneurs have made claims similar to those in the 90s' about the Internet with regard to Big Data.

Thiel, in Packer's account, has also given up on the future. Or at least the future as it was imagined in the 1950s. No space colonies, underwater cities, or extreme engineering projects. As one of Thiel's investment groups says in its prospectus, "We wanted flying cars. Instead we got a 140 characters." Pulling an iPhone from his pocket, Thiel tells Packer that it's no technological breakthrough. "The information age has made Thiel rich, but it has also been a disappointment to him," Packer writes, "The creation of virtual worlds has turns out to be no substitute for advances in the physical world." Jobs and wealth flow from improvements in manufacturing and industry, not just from shuffling electrons and dollars - the two are synonymous today - around the planet. And, to Thiel's liking, not enough attention is being paid to the moving around of atoms and molecules - traditional industry - as opposed to bytes. ((The fact that Thiel made his fortune via Internet ventures is an irony not lost on Packer or this reader.))In recent years, economists and entrepreneurs have made claims similar to those in the 90s' about the Internet with regard to Big Data.

But is Big Data, James Glanz asked in a recent New York Times op-ed, going to be an "economic dud"? ((Glanz used to report on science and technology - he has a Ph.D. in astrophysics - and then served as the Times' Baghdad bureau chief for several years before rotating back to the U.S.)) Or is Big Data the "new oil" as a report by the World Economic Forum claimed?

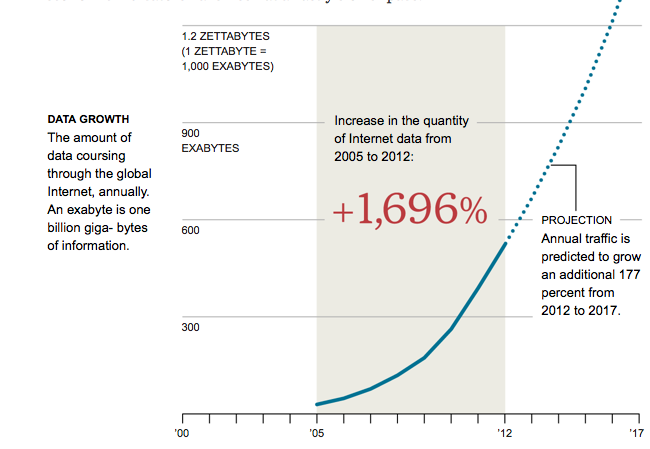

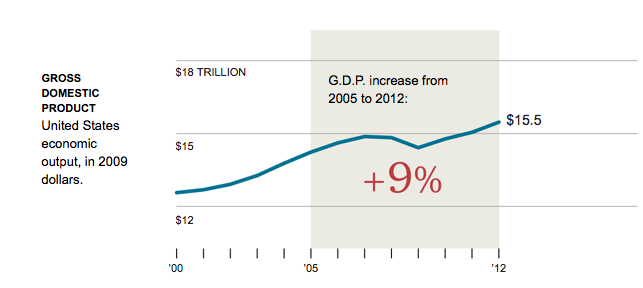

Glanz includes two useful graphics with his piece:

Despite the incomprehensible amount of data sluicing throughout the global pipes of the Internet, U.S. economic output has grown at a very modest amount (even after taking the Great Recession into account). One interpretation is that we still live and work in an economy based on stuff. An economics professor Glanz interviewed evaluated the "new oil" claim and deemed it "promotional nonsense." Data, big or otherwise, isn't comparable to the value of real fuel and the real vehicles it powers.

Despite the incomprehensible amount of data sluicing throughout the global pipes of the Internet, U.S. economic output has grown at a very modest amount (even after taking the Great Recession into account). One interpretation is that we still live and work in an economy based on stuff. An economics professor Glanz interviewed evaluated the "new oil" claim and deemed it "promotional nonsense." Data, big or otherwise, isn't comparable to the value of real fuel and the real vehicles it powers.

Glanz doesn't totally dismiss the transformative effects that Big Data might have...perhaps these won't be felt for years or decades and, of course, it's difficult to disentangle its potential impact from other variables. Paul Krugman, in a response to Glanz's piece, counseled patience. But he also recommended healthy skepticism to counter the hype around emerging technologies like Big Data and so forth. ((Krugman draws on some economic history by Stanford's Paul David including David's 1989 paper "The Dynamo and the Computer: A Historical Perspective on the Modern Productivity Paradox.")) This same skepticism should extend to stuff-based emerging technologies, to be sure. K. Eric Drexler's new book Radical Abundance offers an updated version of his radical vision for what was once called molecular engineering, later to be renamed nanotechnology and, now, "atomically-precise manufacturing."

Here is where some perspectives from the history of technology can help give a better understanding. It's entirely possible that the lives of many many Americans may be affected by Big Data in more and unanticipated ways as corporations and government agencies continue to exploit its potential. But should we expect that anywhere near as many people will participate in and draw wages from working with it as say, Detroit's auto industry c. 1950?

Glanz draws upon a useful historical analogy, citing Harold Platt's 1991 book The Electric City in which one finds similar curves showing the booming rate at which Chicago adopted electric power a century ago. Despite similar curves for the data explosion, electricity - just as intangible as Tweets, Bitcoins, and Instagrams are today - had a far more powerful effect on reshaping the material culture of industrial and domestic life in the U.S. and overseas. Matter still matters. Remembering the world of the real - hardly a desert - and the tangible nature of our technology, is one way toward using it in a more thoughtful manner and remembering the implications for doing so.