Timothy Leary SMI²LEs at Carl Sagan

People with expansive ideas for the technological future have to do considerable work to retain control and ownership of their ideas.This is an inevitable tension that arises for visioneers as one of their key activities is to promote their visions to the public and policy makers in the hopes of generating publicity, acceptance, and perhaps even realization. ((Gerard O’Neill even titled a chapter of The High Frontier (in keeping with the spirit of the time) “Taking It to the People.”))But what do you do when your ideas are co-opted by someone who's more famous than you, perhaps even infamous? Once you have taken “it” to the people, you can’t always control how and what the “people” will do with it. A great example of this is found in the case of Timothy Leary. After his release from jail on drug charges in 1976, Leary began to advocate a new agenda which riffed on some of O’Neill’s work. Leary called his plans SMI²LE, an acronym for “Space Migration, Intelligence Increase, Life Extension.” (This video gives an overview...of sorts.) ((O’Neill was careful to distance himself from them. In practice, he largely ignored Leary, figuring the former LSD guru’s trippy reputation would speak for itself.)) I recently found some new documents that shed additional light on Leary's evolving conceptualization of O'Neill's ideas. What first caught my attention was some 1974 correspondence between Leary and Cornell's most famous scientist, planetary astronomer Carl Sagan. In February-March of 1974, Leary and Sagan exchanged a series of letters, Sagan writing from his office in Ithaca and Leary from his cell in Vacaville, California. I was only able to locate one side of the correspondence - Sagan to Leary; presumably, once Sagan's papers are available at the Library of Congress, the other side of the exchange might emerge. (One tasty tidbit - Leary called Sagan a "true profit" prompting the Cornell scientist to ask if that was a "conscious or accidental pun." Sagan, of course, would garner considerable rewards once the TV series and book Cosmos came out in 1980.)

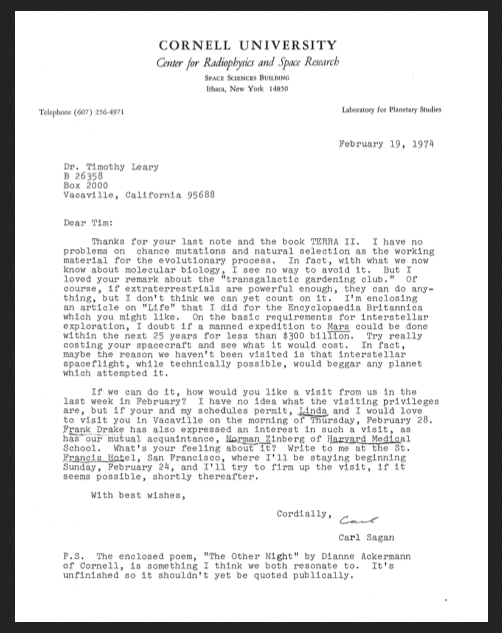

I recently found some new documents that shed additional light on Leary's evolving conceptualization of O'Neill's ideas. What first caught my attention was some 1974 correspondence between Leary and Cornell's most famous scientist, planetary astronomer Carl Sagan. In February-March of 1974, Leary and Sagan exchanged a series of letters, Sagan writing from his office in Ithaca and Leary from his cell in Vacaville, California. I was only able to locate one side of the correspondence - Sagan to Leary; presumably, once Sagan's papers are available at the Library of Congress, the other side of the exchange might emerge. (One tasty tidbit - Leary called Sagan a "true profit" prompting the Cornell scientist to ask if that was a "conscious or accidental pun." Sagan, of course, would garner considerable rewards once the TV series and book Cosmos came out in 1980.) But even from Sagan's letters, it's possible to get a sense of what the two were discussing. Sagan had seen a copy of Leary's 1973 book Terra II: The Starseed Transmission. The book was inspired by the 1973 arrival of comet Kohoutek, which some hippie cultists saw as a harbinger of doom, inspired Leary to write a short tract he “transmitted” from the “black hole” of Folsom Prison. ((Dr. Timothy Leary, Starseed (San Francisco: Level Press, 1973)). This essay was reprinted in Leary’s 1977 book Neuropolitics.)) In Starseed, Leary claimed that he was preparing “a complete systematic philosophy: cosmology, politic, epistemology, ethic, aesthetic, ontology, and the most hopeful eschatology ever specified.” Like astrologers of the Middle Ages, Leary claimed Kohoutek (the “starseed” in Leary’s title) meant a “higher Intelligence has already established itself on earth, writ its testament within our cells, decipherable by our nervous system. That it’s about time to mutate. Create and transmit the new philosophy…Starseed will turn-on the new network.”A note on dates is in order here: Although Leary became a devotee and proselytizer of O'Neill's space settlements, he harbored his own spacey ideas before O'Neill's September 1974 Physics Today article brought him public attention.What did Sagan think of Leary's conjectures? In February 1974, he said "I have no problems on chance mutations and natural selection as the working material for the evolutionary process. In fact, wity what we now know about molecular biology, I see no way to avoid it." Praising Leary's idea for a "transgalactic gardening club" - a reference I believe to the idea that humans would consciously evolve themselves in the same way that plant breeders had changed and "improved" things like roses and corn - Sagan also said he didn't think this option was something "we can count on yet."Leary must have also broached the topic of space migration because Sagan writes: "...maybe the reason we haven't been visited [by extraterrestrials] is that interstellar spaceflight, while technically possible, would beggar any planet which attempted it." Sagan concludes by trying to arrange a prison visit with Leary, possibly with Frank Drake (of Drake's equation and SETI fame) and Harvard's Norman Zinberg (who had studied drug addiction).This was the point in the letters which blew my mind - Sagan sitting down in the visitation room of a California State Prison to chat with Leary about space migration and directed evolution? Even more remarkable was the fact that, just a few days after writing Leary, Sagan had a highly public showdown with cosmic catastrophist Immanuel Velikovsky. The two squared off at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science to debate Velikovsky's scientifically dubious idea that Venus was formed from a comet ejected from Jupiter just several thousand years ago. ((Michael Gordin's fantastic book The Pseduoscience Wars addresses this in wonderfully detail.))So - on one hand, we have Sagan doing a public smackdown of Velikovsky's interpretation of planetary origins and human history. At the very same time, he was working to set up a meeting with Timothy Leary, one of the most notorious counterculture icons and promoter of his own set of scientifically questionable ideas.How can we make sense of this seeming contradiction? Perhaps it just reflects the contingency and chaos of the time. Maybe. But, whereas Velikovsky's ideas were a direct challenge to the science foundation underlying Sagan's professional research, Leary's musing about space migration and cosmic evolution posed no such threat.The 1970s were a fertile meeting ground for all sorts of mainstream and alternative scientists and scientific ideas. Gerard O'Neill's proposed ideas for space settlements, hippie physicists investigated the paranormal, and the counterculture's embrace of catastrophist theories put forth by the decidedly ungroovy Immanuel Velikovsky all co-existed with "traditional" academic and corporate research.

But even from Sagan's letters, it's possible to get a sense of what the two were discussing. Sagan had seen a copy of Leary's 1973 book Terra II: The Starseed Transmission. The book was inspired by the 1973 arrival of comet Kohoutek, which some hippie cultists saw as a harbinger of doom, inspired Leary to write a short tract he “transmitted” from the “black hole” of Folsom Prison. ((Dr. Timothy Leary, Starseed (San Francisco: Level Press, 1973)). This essay was reprinted in Leary’s 1977 book Neuropolitics.)) In Starseed, Leary claimed that he was preparing “a complete systematic philosophy: cosmology, politic, epistemology, ethic, aesthetic, ontology, and the most hopeful eschatology ever specified.” Like astrologers of the Middle Ages, Leary claimed Kohoutek (the “starseed” in Leary’s title) meant a “higher Intelligence has already established itself on earth, writ its testament within our cells, decipherable by our nervous system. That it’s about time to mutate. Create and transmit the new philosophy…Starseed will turn-on the new network.”A note on dates is in order here: Although Leary became a devotee and proselytizer of O'Neill's space settlements, he harbored his own spacey ideas before O'Neill's September 1974 Physics Today article brought him public attention.What did Sagan think of Leary's conjectures? In February 1974, he said "I have no problems on chance mutations and natural selection as the working material for the evolutionary process. In fact, wity what we now know about molecular biology, I see no way to avoid it." Praising Leary's idea for a "transgalactic gardening club" - a reference I believe to the idea that humans would consciously evolve themselves in the same way that plant breeders had changed and "improved" things like roses and corn - Sagan also said he didn't think this option was something "we can count on yet."Leary must have also broached the topic of space migration because Sagan writes: "...maybe the reason we haven't been visited [by extraterrestrials] is that interstellar spaceflight, while technically possible, would beggar any planet which attempted it." Sagan concludes by trying to arrange a prison visit with Leary, possibly with Frank Drake (of Drake's equation and SETI fame) and Harvard's Norman Zinberg (who had studied drug addiction).This was the point in the letters which blew my mind - Sagan sitting down in the visitation room of a California State Prison to chat with Leary about space migration and directed evolution? Even more remarkable was the fact that, just a few days after writing Leary, Sagan had a highly public showdown with cosmic catastrophist Immanuel Velikovsky. The two squared off at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science to debate Velikovsky's scientifically dubious idea that Venus was formed from a comet ejected from Jupiter just several thousand years ago. ((Michael Gordin's fantastic book The Pseduoscience Wars addresses this in wonderfully detail.))So - on one hand, we have Sagan doing a public smackdown of Velikovsky's interpretation of planetary origins and human history. At the very same time, he was working to set up a meeting with Timothy Leary, one of the most notorious counterculture icons and promoter of his own set of scientifically questionable ideas.How can we make sense of this seeming contradiction? Perhaps it just reflects the contingency and chaos of the time. Maybe. But, whereas Velikovsky's ideas were a direct challenge to the science foundation underlying Sagan's professional research, Leary's musing about space migration and cosmic evolution posed no such threat.The 1970s were a fertile meeting ground for all sorts of mainstream and alternative scientists and scientific ideas. Gerard O'Neill's proposed ideas for space settlements, hippie physicists investigated the paranormal, and the counterculture's embrace of catastrophist theories put forth by the decidedly ungroovy Immanuel Velikovsky all co-existed with "traditional" academic and corporate research.

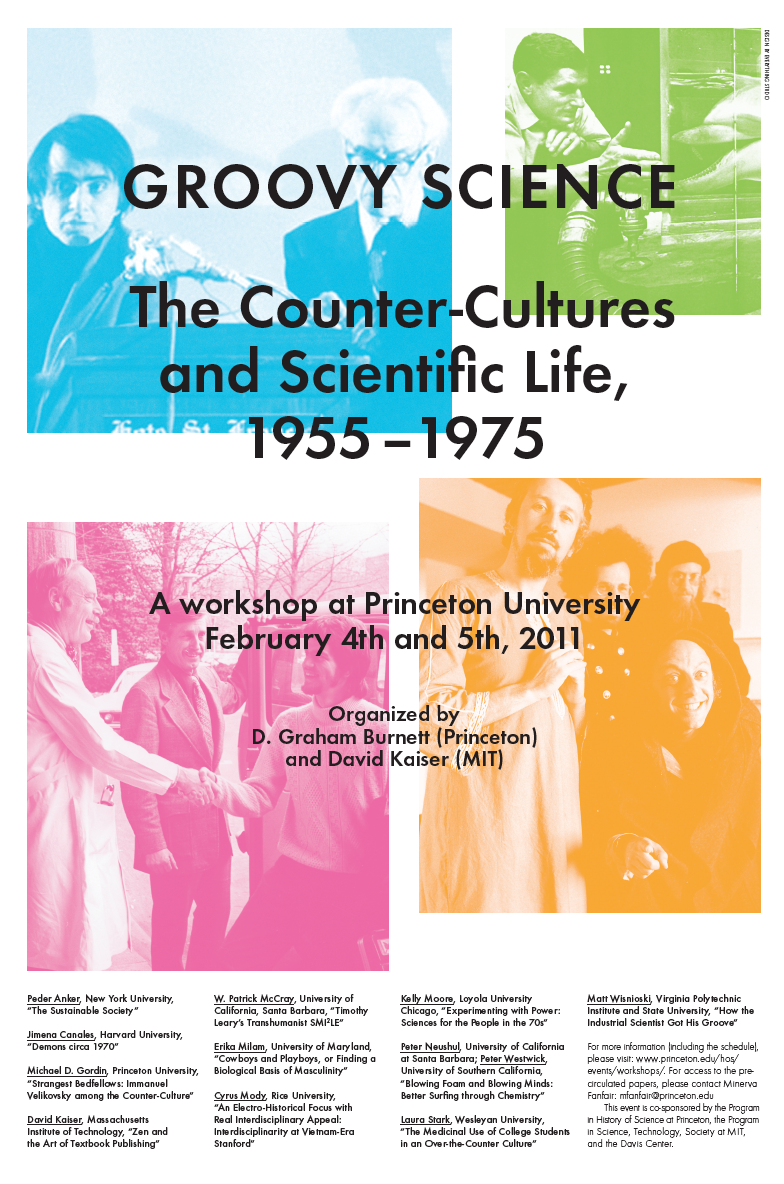

In fact, the co-existence of these many shades and hues of science in the 1970s challenges our very ideas of what mainstream and fringe actually were. ((This point, in fact, was the basis for a great 2011 workshop at Princeton University called Groovy Science. Papers from this are being worked into an edited volume...)) I think it's best not to see them in such Manichean terms - real versus fringe - but to accept that, like the Copenhagen model of complementarity, they co-exist. This was not pseudoscience. Just a different kind of science that helped generate a new kind of scientific American.