Considering Countercultural Architects

When I'm in southern Arizona, there are a few places I especially look forward to visiting. One of them is the Titan Missile Museum located about an hour’s drive south of Tucson. Once located out in the middle of the Sonoran desert, the museum is now slowly being swallowed by acres of retirement houses. Besides being redolent of all the Cold War nuclear secrecy stuff that Alex Wellerstein writes about, it’s also a fascinating architectural experience – taking the elevator deep underground leads to networks of tunnels and small rooms where people would launch Armageddon.

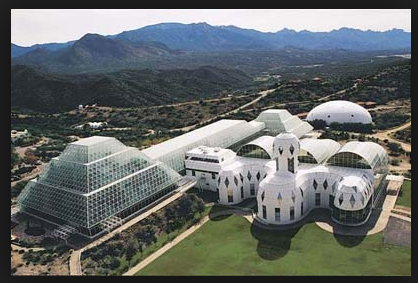

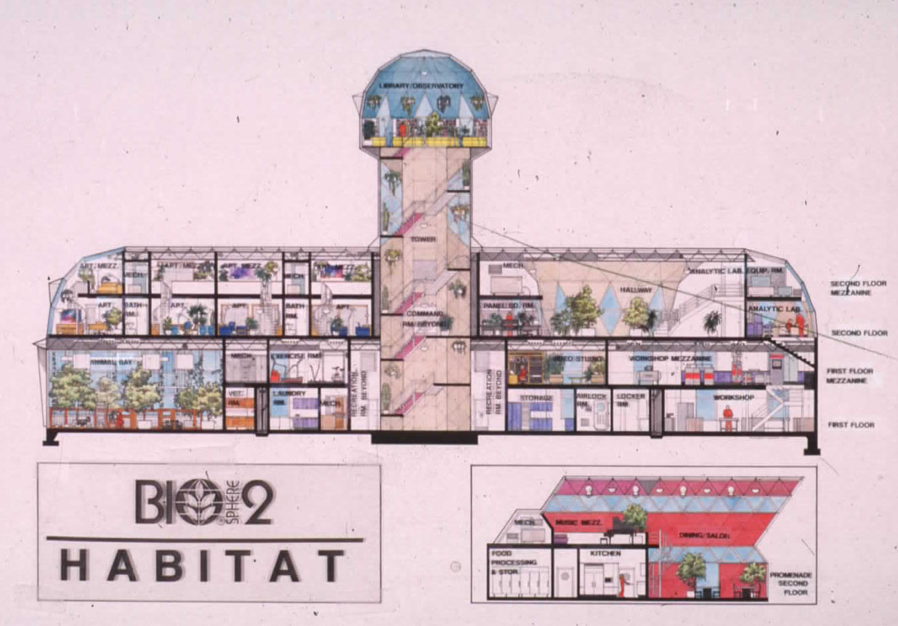

Heading the other direction from Tucson, near the town of Oracle, is Biosphere 2. BS2 also was also constructed in the shadow of an apocalypse. Only in this case, it was the imagined catastrophe of the ecological type. Built in the 1980s, BS2 was inspired in part by the space colonization ideas of Gerard O'Neill. The idea was create an ecologically self-contained system so as both better understand the workings of our planet and also develop the technologies in case there was a need to move off-world.

Built in the 1980s, BS2 was inspired in part by the space colonization ideas of Gerard O'Neill. The idea was create an ecologically self-contained system so as both better understand the workings of our planet and also develop the technologies in case there was a need to move off-world. It is a stunning place to visit – nestled in the shadow of the Catalina mountains, a compact metal and glass jewel containing some six different biomes including a miniature ocean. Undergirding this “ecosphere” is a similarly impressive “technosphere” which resembles that found at the missile museum in more ways than one. Like the Missile Museum, BS2 - a model of how we might live in a type of ecological equilibrium - is also slowly being outflanked by suburban sprawl.If one continues north, a third destination – Arcosanti – can be added to this tour of technoscientific marvels.Like Biosphere 2, Arcosanti was a hybrd of technology, ecology, and architecture. The recent death of Paolo Soleri, the driving force behind Arcosanti, prompted me to think again about the connections between marvels like Biosphere 2 as well as O'Neill’s space colony designs. It also pushed me to think more about the nature of success and failure.An immigrant from Italy, Soleri came to the U.S. in 1947 to apprentice with Frank Lloyd Wright. Around this time, he began to develop a design philosophy in which architecture combined with ecology – what he called arcology.

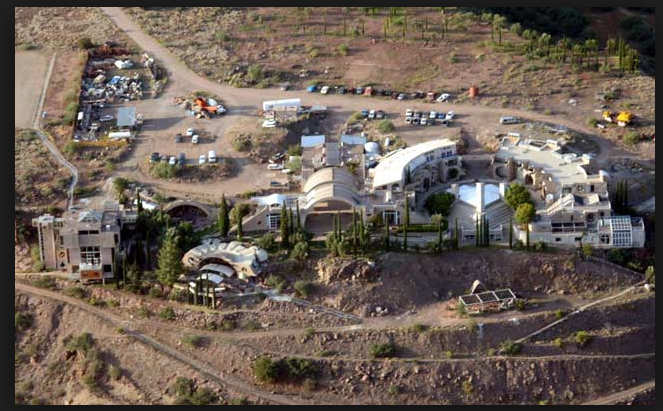

It is a stunning place to visit – nestled in the shadow of the Catalina mountains, a compact metal and glass jewel containing some six different biomes including a miniature ocean. Undergirding this “ecosphere” is a similarly impressive “technosphere” which resembles that found at the missile museum in more ways than one. Like the Missile Museum, BS2 - a model of how we might live in a type of ecological equilibrium - is also slowly being outflanked by suburban sprawl.If one continues north, a third destination – Arcosanti – can be added to this tour of technoscientific marvels.Like Biosphere 2, Arcosanti was a hybrd of technology, ecology, and architecture. The recent death of Paolo Soleri, the driving force behind Arcosanti, prompted me to think again about the connections between marvels like Biosphere 2 as well as O'Neill’s space colony designs. It also pushed me to think more about the nature of success and failure.An immigrant from Italy, Soleri came to the U.S. in 1947 to apprentice with Frank Lloyd Wright. Around this time, he began to develop a design philosophy in which architecture combined with ecology – what he called arcology. Soleri’s ideas resonated with emerging concepts about managing the planet and its resources like a spacecraft. Promoted and popularized by economist Kenneth Boulding and futurist Bucky Fuller, “spaceship earth” became one of the dominant metaphors of the 1960s. As Soleri’s obituary notes, the Italian architect believed human habitation had to become more thrifty, space-wise, and compact.In the late 1960s, Soleri bought more than 800 acres of desert north of Phoenix and, along with a cohort of eager acolytes, began to design and build Arcosanti. Describes as “Buckminster Fuller meets Buck Rogers,” Arcosanti was designed as an architectural and social experiment. Early visitors paid for the privilege of working there and Soleri went on to become an iconic and controversial figure. Planned as an ecologically sound human habitat in the wake of the first Earth Day, Arcosanti appealed to the many “seekers” who populated the communal living and "back-to-the-land" movements of the era. Originally designed to house 5,000 people, fewer than 200 called Arcosanti home at any one time. But, over the years, some 7,000 people lived there in a nest of poured-concrete structures, some domed and others with soaring arches.

Soleri’s ideas resonated with emerging concepts about managing the planet and its resources like a spacecraft. Promoted and popularized by economist Kenneth Boulding and futurist Bucky Fuller, “spaceship earth” became one of the dominant metaphors of the 1960s. As Soleri’s obituary notes, the Italian architect believed human habitation had to become more thrifty, space-wise, and compact.In the late 1960s, Soleri bought more than 800 acres of desert north of Phoenix and, along with a cohort of eager acolytes, began to design and build Arcosanti. Describes as “Buckminster Fuller meets Buck Rogers,” Arcosanti was designed as an architectural and social experiment. Early visitors paid for the privilege of working there and Soleri went on to become an iconic and controversial figure. Planned as an ecologically sound human habitat in the wake of the first Earth Day, Arcosanti appealed to the many “seekers” who populated the communal living and "back-to-the-land" movements of the era. Originally designed to house 5,000 people, fewer than 200 called Arcosanti home at any one time. But, over the years, some 7,000 people lived there in a nest of poured-concrete structures, some domed and others with soaring arches. Soleri combined an expansive vision of the future made possible by his designs with actual design and construction work to advance his vision. In true visioneer fashion, he also attracted a community of followers as well as some detractors. “When so many others were theorizing,” said Jeffrey Cook, a professor of architecture at Arizona State University, “Soleri went out into the desert and actually built his vision with his own hands.” This same “vision + engineering + advocacy” formula marked Gerard O'Neill’s activism for space-based settlements.Soleri and O'Neill attracted some of the same critics. In a 1977 book on space colonies, Nobel-winning biologist George Wald – no fan of O'Neill’s visioneering – critiqued Soleri’s architecture as “bony constructions in the American desert…Can you imagine trying to live, even to raise children in such a place?” In the same book, Soleri himself expanded on the “eschatological concerns…the purposefulness of life” of O'Neill’s space colonies and space exploration in general. The apocalyptic aspects of the missile silos that dotted the Arizona landscape went uncommented on. Perhaps there was nothing really to say, Soleri seeing his designs and perhaps O'Neill’s as a more hopeful counter to missile-filled holes in the ground.It is easy to write off Arcosanti, O'Neill’s space colonies, and Biosphere 2 as failed examples of a certain hippie-era utopianism. None of them accomplished what their designers had originally imagined for them. But the chain of influence between them is striking. Arcosanti expressed some of the same design ideas that O'Neill included in his plans for space colonies. In both cases, architecture, engineering, and ecological thinking were inseparable. ((Peder Anker, “The Ecological Colonization of Space,” Environmental History, 2005, 10, 2: 239-68 discusses some aspects of this.)) Both held strong appeal to that somewhat fuzzy demographic group known as the “counterculture.” However, I’ve seen no evidence – other than some shared space in a book and some shared ire from critics – that O'Neill was much aware of what Soleri was building in the Arizona desert. Of course, the lines of influence from O'Neill and Soleri to Biosphere 2 are much more clear and direct. Biosphere 2 was, like Arcosanti, a utopian community of sorts, a social as well as ecological experiment. It was also seen a prototype to test some of the design concepts and technologies that might be necessary to construct a self-contained ecological system in space.A key different between Arcosanti and either Biospere 2 or O'Neill’s concepts is, oddly enough, the future. O'Neill’s visioneering has inspired a new crop of Space 2.0 types but few have the bold and expansive plans he once had. Biosphere 2 – still open for tours – is managed by the University of Arizona as an ecological research station but it’s no longer operated as a closed ecological system. In comparison, Arcosanti still seems to have a future. “Part Mos Eisley, part Ozymandias,” as one writer recently described it, some 60 people still live and work at the “urban lab” which they see as a model for sustainable living. As a recruitment poster for Arcosanti says “If you are truly concerned about the problems of pollution, waste, energy depletion, land, water, air and biological conservation, poverty, segregation, intolerance, population containment, fear and disillusionment – Join us.” There are other futuristic planned communities on the drawing board - the Seasteading "movement" is one intriguing example - so perhaps Arcosanti won't be the last experiment of its type.

Soleri combined an expansive vision of the future made possible by his designs with actual design and construction work to advance his vision. In true visioneer fashion, he also attracted a community of followers as well as some detractors. “When so many others were theorizing,” said Jeffrey Cook, a professor of architecture at Arizona State University, “Soleri went out into the desert and actually built his vision with his own hands.” This same “vision + engineering + advocacy” formula marked Gerard O'Neill’s activism for space-based settlements.Soleri and O'Neill attracted some of the same critics. In a 1977 book on space colonies, Nobel-winning biologist George Wald – no fan of O'Neill’s visioneering – critiqued Soleri’s architecture as “bony constructions in the American desert…Can you imagine trying to live, even to raise children in such a place?” In the same book, Soleri himself expanded on the “eschatological concerns…the purposefulness of life” of O'Neill’s space colonies and space exploration in general. The apocalyptic aspects of the missile silos that dotted the Arizona landscape went uncommented on. Perhaps there was nothing really to say, Soleri seeing his designs and perhaps O'Neill’s as a more hopeful counter to missile-filled holes in the ground.It is easy to write off Arcosanti, O'Neill’s space colonies, and Biosphere 2 as failed examples of a certain hippie-era utopianism. None of them accomplished what their designers had originally imagined for them. But the chain of influence between them is striking. Arcosanti expressed some of the same design ideas that O'Neill included in his plans for space colonies. In both cases, architecture, engineering, and ecological thinking were inseparable. ((Peder Anker, “The Ecological Colonization of Space,” Environmental History, 2005, 10, 2: 239-68 discusses some aspects of this.)) Both held strong appeal to that somewhat fuzzy demographic group known as the “counterculture.” However, I’ve seen no evidence – other than some shared space in a book and some shared ire from critics – that O'Neill was much aware of what Soleri was building in the Arizona desert. Of course, the lines of influence from O'Neill and Soleri to Biosphere 2 are much more clear and direct. Biosphere 2 was, like Arcosanti, a utopian community of sorts, a social as well as ecological experiment. It was also seen a prototype to test some of the design concepts and technologies that might be necessary to construct a self-contained ecological system in space.A key different between Arcosanti and either Biospere 2 or O'Neill’s concepts is, oddly enough, the future. O'Neill’s visioneering has inspired a new crop of Space 2.0 types but few have the bold and expansive plans he once had. Biosphere 2 – still open for tours – is managed by the University of Arizona as an ecological research station but it’s no longer operated as a closed ecological system. In comparison, Arcosanti still seems to have a future. “Part Mos Eisley, part Ozymandias,” as one writer recently described it, some 60 people still live and work at the “urban lab” which they see as a model for sustainable living. As a recruitment poster for Arcosanti says “If you are truly concerned about the problems of pollution, waste, energy depletion, land, water, air and biological conservation, poverty, segregation, intolerance, population containment, fear and disillusionment – Join us.” There are other futuristic planned communities on the drawing board - the Seasteading "movement" is one intriguing example - so perhaps Arcosanti won't be the last experiment of its type.