Horizons of Expectation

Not all futures are created equal.One of the meta-points of The Visioneers is that the future is not a neutral space that we as individuals or as a society move into. Rather, the future is politically contested terrain, an arena of speculation where diverse interests meet, debate, argue, and compromise. In the “predictive space” of technological tomorrows, the future exists as an unstable entity which different individuals and groups vie to construct and claim through their writings, their designs, and their activities while marginalizing alternative futures.The “Forum” section in the new American Historical Review takes up the absorbing topic of “histories of the future” in some innovative and provocative ways. ((Unfortunately, these article are behind a pay wall…hopefully, you’ve access to these excellent essays via a personal or institutional subscription)) The editor of the Forum is David C. Engerman, a historian at Brandeis University; his super 2009 book Know Your Enemy examined the network of scholars who engaged in “Soviet Studies” during the Cold War. In his introduction to the AHR Forum, Engerman draws on the work of German historian Reinhart Koselleck. His book Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time argued that scholars must consider “horizons of expectation” in addition to “spaces of experience.” It’s impossible to fully analyze and understand historical experience without taking these expectations of the future into account. As Engerman puts it, “how historical subjects imagined their futures is crucial to understanding their pasts.” I couldn't agree more.In The Visioneers, I show how technological visionaries engaged in politics – primarily at local levels – to build support for their ideas and quash rival views of the technological future. The essays in the AHR Forum likewise address politics but at the higher levels of the state and geopolitics. For example, Jenny Andersson’s essay “The Great Future Debate and the Struggle for the World” examines how futurology on both sides of the Iron Curtain “was a veritable battleground for different future visions.” Andersson shows how even definitions of “futurology” varied depending on whether one was a West German or East German futurist. Here, we see futurology as well as the future freighted with all sorts of political baggage. Andersson’s realization that writing histories of the future is methodologically challenging is something I learned when writing my own book. For example, archival materials left by futurists are often not readily available and instead have to be “retrieved from garages and storage rooms.” I have a good story about this which I share in public talks.Politics naturally conjures questions of power. Engerman describes how the Forum’s authors built on insights from anthropologist Johannes Fabian. Fabian's book Time and Power observed that “geopolitics has its ideological foundations in chronopolitics.” As a result, visions of the future are not “natural resources” but “ideologically constructed instruments of power" which makes them far from neutral. This theme comes out quite strongly in an essay by historian Matthew Connelly (which he co-authored with nine other people, perhaps an AHR record). “Team Connelly” focus on interactions of forecasters and planners with military leaders and politicians during the Cold War as they attempted to predict Soviet strategic intentions in order to prepare America’s nuclear war plans. From the pre-Joe 1 days through Ike’s 50s and the High Cold War and well into détente and “Cold War redux” of the Carter-Reagan years, these wildly inaccurate estimates were shaped by fights over power and resources within the Pentagon. Just as the Soviet Union and the U.S. offered contrasting images of the communist/capitalist future as an ideological tool, the future was also something wielded in Beltway bureaucratic battles. At the same time, it’s through the lens of nuclear war that we see how our understanding of Cold War culture is complicated by the fact that, for many people, there was no future (cue Sex Pistols). Connelly et al. draw nicely on French psychiatrist Eugène Minkowski’s work on World War One survivors. People “live the future” based on a balance between activity and expectation…and if expectations of the future are nil, then one should expect to see this reflected in their activity (and films, art, books, etc.).Team Connelly also refer to Marc Bloch’s “problem of prevision” – predictions about the future can be “self-falsifying” and predictions that today seem implausible “may therefore have been the most important of all.” This is an elegant phrasing of two ideas I tried to bring out in The Visioneers. First, one shouldn’t judge past predictions of the future on the basis of how “crazy” they seem today. While my characters certainly proposed some radical schemes, they might appear less so (or at least more understandable) when seen in context. Second, it’s hard to judge the effects of the futures that didn’t happen. Often, the activities of visioneers were like "dark matter" tugging on the more visible galaxy of mainstream science and engineering as well as public imagination and state policy.The essays by Engerman, Andersson, and Team Connelly all grapple with the surge in “future studies” – RAND figures prominently – that marks the Cold War and especially the late 1960s and early 1970s. ((A third essay in the Forum, by Manu Goswami, deals with the early 20th century)). People have always looked to the future. But, in the late 1960s, begins to unfold, a growing number of scientists, writers, and other experts were also looking at the future. Professional “futurologists” became well-paid celebrities sought out for their advice. Like many other areas of Cold War-era technology, this fascination with the future originated within the military-industrial complex. In the late 1960s, tools developed for military planning made their way to the corporate world, aided by the growing availability of computers and a belief that complex economic and societal situations could be modeled. American businesses started retaining more and more specialists, including science fiction writers, “to plot the future much as medieval monarchs used to have court-astrologers around.” ((William H. Honan. “The Futurists Take over the Jules Verne Business.” New York Times, April 9, 1967.))While RAND researchers began to apply skills honed for modeling war and business to address ‘60s-era social issues, others founded their own enterprises such as the Institute for the Future based in Palo Alto, California. In 1966, as part of the “civilianizing” of futures research, a few hundred forward-looking people joined the World Future Society. Within a decade, its membership had shot to 25,000. Futurology entered a golden age and, with it, came the mass-marketed futurist. Hugely popular books about the technological future, such as Alvin Toffler’s book Future Shock (1970) and Daniel Bell’s The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (1973), flew off bookshelves. This “pop futurism” carried a common message: The 1970s, poised between two technological eras, one of industry and the other of information, would be an era of abrupt change. The future became an object of serious scholarly inquiry as an entire academic edifice of journals, conferences, and experts devoted to looking over the horizon emerged. Trying to find an alternate to “the whole Cartesian trip,” American and European universities offered hundreds of courses that addressed some aspect of the future.The future and technology have always been interwoven. The sheer act of building something, be it a stone axe or spaceship, implies an imagined future need and use. Although the AHR Forum’s essays do not explicitly treat technology (or science) as a central variable, technological change was the major variable in these classes as economists, computer scientists, and sociologists attempted to understand the future more “scientifically” and propose ways in which society might navigate toward alternate, more desirable futures. In response to the “bourgeoisie-capitalist” scenarios proffered by groups with corporate or military connections, a growing swell of anti-technocratic, publicly oriented intellectuals spun dissenting futurology. Senator Edward Kennedy, taking a jab at the excesses of Apollo, said in 1975, “We must be pioneers in time, rather than space.” ((John D. Douglas, “The Future of Futurism: An Analysis,” Science News, 1975, 107, 26: 416-17.))As Team Connelly notes, a good deal of historians’ attention to the future has been on intellectual and cultural history including utopian/dystopian visions as well as “visual and literary representations of things to come.” Valuable as these approaches are, they leave lots of territory open for future exploration. More histories of Koselleck’s “horizons of expectation” – not only at the state and geopolitical levels but in ways that also incorporate social, economic, and scientific/technological history – can help reveal how past predictions of the future have helped shape where we are today.

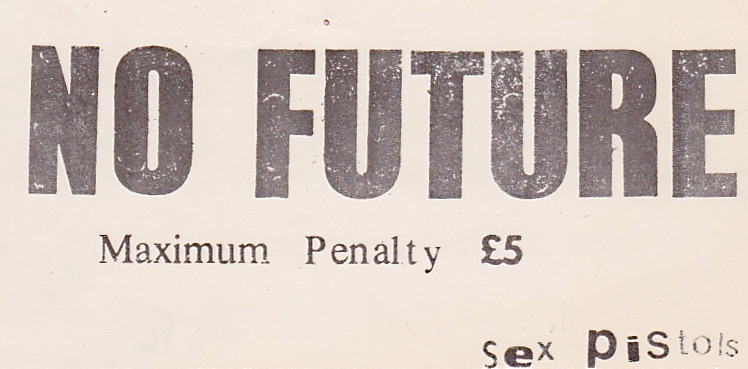

At the same time, it’s through the lens of nuclear war that we see how our understanding of Cold War culture is complicated by the fact that, for many people, there was no future (cue Sex Pistols). Connelly et al. draw nicely on French psychiatrist Eugène Minkowski’s work on World War One survivors. People “live the future” based on a balance between activity and expectation…and if expectations of the future are nil, then one should expect to see this reflected in their activity (and films, art, books, etc.).Team Connelly also refer to Marc Bloch’s “problem of prevision” – predictions about the future can be “self-falsifying” and predictions that today seem implausible “may therefore have been the most important of all.” This is an elegant phrasing of two ideas I tried to bring out in The Visioneers. First, one shouldn’t judge past predictions of the future on the basis of how “crazy” they seem today. While my characters certainly proposed some radical schemes, they might appear less so (or at least more understandable) when seen in context. Second, it’s hard to judge the effects of the futures that didn’t happen. Often, the activities of visioneers were like "dark matter" tugging on the more visible galaxy of mainstream science and engineering as well as public imagination and state policy.The essays by Engerman, Andersson, and Team Connelly all grapple with the surge in “future studies” – RAND figures prominently – that marks the Cold War and especially the late 1960s and early 1970s. ((A third essay in the Forum, by Manu Goswami, deals with the early 20th century)). People have always looked to the future. But, in the late 1960s, begins to unfold, a growing number of scientists, writers, and other experts were also looking at the future. Professional “futurologists” became well-paid celebrities sought out for their advice. Like many other areas of Cold War-era technology, this fascination with the future originated within the military-industrial complex. In the late 1960s, tools developed for military planning made their way to the corporate world, aided by the growing availability of computers and a belief that complex economic and societal situations could be modeled. American businesses started retaining more and more specialists, including science fiction writers, “to plot the future much as medieval monarchs used to have court-astrologers around.” ((William H. Honan. “The Futurists Take over the Jules Verne Business.” New York Times, April 9, 1967.))While RAND researchers began to apply skills honed for modeling war and business to address ‘60s-era social issues, others founded their own enterprises such as the Institute for the Future based in Palo Alto, California. In 1966, as part of the “civilianizing” of futures research, a few hundred forward-looking people joined the World Future Society. Within a decade, its membership had shot to 25,000. Futurology entered a golden age and, with it, came the mass-marketed futurist. Hugely popular books about the technological future, such as Alvin Toffler’s book Future Shock (1970) and Daniel Bell’s The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (1973), flew off bookshelves. This “pop futurism” carried a common message: The 1970s, poised between two technological eras, one of industry and the other of information, would be an era of abrupt change. The future became an object of serious scholarly inquiry as an entire academic edifice of journals, conferences, and experts devoted to looking over the horizon emerged. Trying to find an alternate to “the whole Cartesian trip,” American and European universities offered hundreds of courses that addressed some aspect of the future.The future and technology have always been interwoven. The sheer act of building something, be it a stone axe or spaceship, implies an imagined future need and use. Although the AHR Forum’s essays do not explicitly treat technology (or science) as a central variable, technological change was the major variable in these classes as economists, computer scientists, and sociologists attempted to understand the future more “scientifically” and propose ways in which society might navigate toward alternate, more desirable futures. In response to the “bourgeoisie-capitalist” scenarios proffered by groups with corporate or military connections, a growing swell of anti-technocratic, publicly oriented intellectuals spun dissenting futurology. Senator Edward Kennedy, taking a jab at the excesses of Apollo, said in 1975, “We must be pioneers in time, rather than space.” ((John D. Douglas, “The Future of Futurism: An Analysis,” Science News, 1975, 107, 26: 416-17.))As Team Connelly notes, a good deal of historians’ attention to the future has been on intellectual and cultural history including utopian/dystopian visions as well as “visual and literary representations of things to come.” Valuable as these approaches are, they leave lots of territory open for future exploration. More histories of Koselleck’s “horizons of expectation” – not only at the state and geopolitical levels but in ways that also incorporate social, economic, and scientific/technological history – can help reveal how past predictions of the future have helped shape where we are today.